Written by David Caldwell ·

Cumbria and the Cumbric Language: The Forgotten Celtic Kingdom of the Old North

The Ancient Cymric Kingdom of Cumbria: History, Language, and Legend

Part I – Origins and Geography

Rome’s Departure and the Birth of a Kingdom

When the Roman legions marched south for the last time in the early fifth century, Britain was left exposed to waves of invasion and fragmentation. Yet in the north, beyond Hadrian’s Wall, the Brythonic-speaking communities who had lived under Rome did not vanish. Instead, they reorganised themselves into new polities. Among these was Cumbria, remembered in Welsh tradition as part of Yr Hen Ogledd - the “Old North.”

The name itself is telling. Cymry is the Welsh word for “our people,” and Cumbria, linguistically and culturally, was one with Wales and Cornwall. The Cumbrians were not outsiders but kin to the wider Brythonic world. As one Victorian historian put it, “the Cymry formed a confederation against the Angles, including both branches of the Celtic race, the Goidels as well as the Brythons.” The idea of Cumbria as a natural division of Britain, stretching across the lands north of the Severn and Avon, survived long after the fall of Rome.

Tribal Foundations

The earliest Cumbrians were likely descendants of the Brigantes, the largest tribe of Roman Britain, along with the Carvetii of Carlisle and the Selgovae of southern Scotland. Under Rome these groups were heavily militarised, providing auxiliaries and guarding the Wall. After Rome’s collapse, they did not disappear but reorganised into a Brythonic kingdom.

Evidence for their survival lies in continuity of place-names and in the persistence of Brythonic Christianity. Saints such as Ninian and Kentigern were received not by “barbarians” but by peoples still living within a Romano-British cultural frame.

Centres of Power

Three sites in particular anchor our understanding of Cumbria:

Carlisle (Caer Luel): The old Roman fort became a key stronghold. Its Brythonic name – Caer meaning fort – shows its continued occupation by native rulers. Carlisle’s walls, still formidable in the Dark Ages, made it a natural capital.

Llwyfenydd (Lyvennet Valley): Remembered in medieval Welsh poetry as a heartland of the Brittonic North, Llwyfenydd represents more than just a settlement – it was a symbolic centre of Cumbric identity. Located south of Crosby Ravensworth, the place-name survives in the Lyvennet river and valley, tying poetry and topography together.

Dumbarton Rock (Alt Clut): Though technically in Strathclyde, this great fortress on the Clyde was often paired with Carlisle as part of the same cultural and political sphere. Chroniclers often refer to the “Kings of Alt Clut and Cumbria” as if their rule was interlinked.

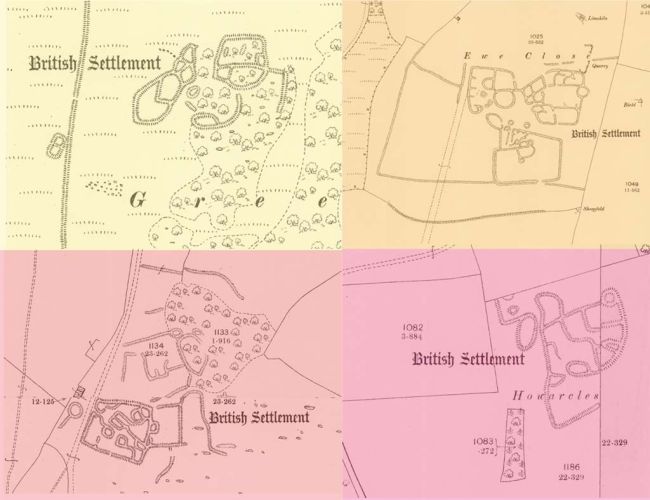

Extracts from 19th century mapping showing ruins south of Crosby Ravensworth in the Lyvennet Valley. Could this be the site of Llwyfenydd?

Reproduced with the permission of the National Library of Scotland under the Creative Commons Attribution (CC-BY) licence

Probable Borders

Defining Cumbria’s extent is notoriously difficult. It was less a fixed state than a coalition of communities. Yet clues survive:

- To the north, Cumbria met the Pictish and Gaelic zones of southern Scotland. Galloway and Ayrshire were contested ground, sometimes Brythonic, sometimes Gaelic.

- To the east, the Pennines and River Derwent likely marked the frontier with Northumbria. The Battle of Chester in 616 cut Cumbria off from Wales, forcing it to look north and west for allies.

- To the west, the Solway Firth and Irish Sea linked Cumbria to sea routes - both a vulnerability to Norse attack and a highway for trade.

- To the south, its influence extended into Lancashire and even northern Cheshire in earlier centuries, though Anglo-Saxon expansion gradually shrank this zone.

One late nineteenth-century source suggested that the whole fertile region around the River Carron was “continually the scene of internecine strife between Romans, Scots, Picts, and Cumbrians,” underlining the shifting, war-torn frontier character of the kingdom.

Cumbria as the “Old North”

What unites these fragments is a sense that Cumbria was the northern frontier of Brythonic civilisation. To its south lay Anglo-Saxon England, to its west the Norse sea-kings, to its north Gaelic Scots, and to its east the Picts. Cumbria endured in this contested zone for centuries, balancing diplomacy and war, but always retaining its Cymric identity.

In the next section, we will explore what made that identity distinct: the Cumbric language, its echoes in place-names and sheep-counting rhymes, and the saints and poets who gave Cumbria its cultural life.

Part II – Language and Society

The Cumbric Language

At the heart of Cumbria’s identity lay its language: Cumbric. This was a branch of the Brythonic Celtic family, which also gave rise to Welsh, Cornish, and Breton. To the Cumbrians themselves, there was little distinction between “Welsh” and “Cumbric” - both were Cymric tongues.

Modern scholars reconstruct Cumbric from three main sources:

- Place-names – Cumbria is studded with names of Brythonic origin:

- Penrith (pen rhyd, “chief ford”)

- Carlisle (Caer Luel, “fort of Luel”)

- Blencathra (blain cathrach, “hill of the chair”)

- Lanercost (llaner gwas, “monastic enclosure”)

- These names survived centuries of Anglo-Saxon and Norse overlay, hinting at a strong underlying Brythonic substrate.

- Legal and dialect survivals – Counting systems used by shepherds in the Pennines and Lakeland dales into the modern period show striking similarities to Welsh numerals. Examples like yan, tyan, tethera, methera, pimp are relics of Cumbric numeracy, passed down orally.

- Medieval glosses – A handful of words preserved in law codes and chronicles hint at Cumbric terms for landholding, kinship, and society. These suggest close alignment with Old Welsh but with local forms.

Linguists argue that Cumbric survived well into the 12th century, with some suggesting it lingered in rural pockets even later. One review in The Scotsman noted that Old Cumbric “was gradually being pushed out by Gaelic from about 1000 AD onwards,” but not extinguished overnight. Cumbria, unlike Pictland, never lost its Brythonic voice suddenly; it faded slowly, absorbed into the swelling tide of English and Gaelic speech.

Religion and the Saints

The Cumbrians were not only a Brythonic people; they were also a Christian one. Christianity had taken root under Rome and endured afterwards, often in tension with pagan survivals.

- St Ninian – Based at Whithorn (Candida Casa) in Galloway in the 5th century, Ninian is credited with bringing Christianity to southern Picts and Cumbrians alike. His cult spread across the Solway.

- St Kentigern (Mungo) – Perhaps the most emblematic saint of Cumbria, Kentigern worked around the Clyde and Carlisle. He is remembered as the founder of Glasgow, but his sphere was broader: a unifier of Brythonic Christianity in the north. Under his patronage, Cumbria’s kings were remembered as pious as well as warlike.

- St Cuthbert – Though usually associated with Northumbria, Cuthbert’s career intersected with Cumbrian lands. Hagiographies note his journeys into these regions, highlighting a borderland where Northumbrian and Cumbrian Christianity overlapped.

Religion reinforced Cumbria’s Cymric identity. Its saints were remembered in Welsh hagiographies, showing that Cumbria was seen as part of the same spiritual world as Wales.

Poetry, Prophecy, and Oral Tradition

Cumbria’s culture was not only political and religious; it was also poetic. Fragments of medieval Welsh poetry preserve the voices of northern bards singing of Cumbrian kings and heroes.

- Aneirin’s Y Gododdin, though centred on Edinburgh (Din Eidyn), celebrates warriors from across the Old North, including Cumbria.

- Taliesin’s poems praise Urien of Rheged, a kingdom overlapping Cumbria, and his son Owain. These verses show how Cumbrian rulers were integrated into the heroic literature of the Cymry.

Prophecy, too, has a Cumbrian root. The figure of Myrddin (Merlin), driven mad after the battle of Arfderydd in 573, wanders the forests of southern Scotland as a wild seer. Later medieval writers made him Arthur’s advisor, but his origin is distinctly Cumbrian: a traumatised Brythonic warlord turned prophet.

Through these legends, Cumbria gave Britain some of its richest mythic figures, remembered not only in history but in the imagination.

Society and Law

Though few Cumbrian legal texts survive, parallels with Welsh law suggest a kin-based society where land was divided among freeholders, and where extended families (gwelyau) held significant rights. Medieval chronicles refer to “kings of the Cumbrians,” but these rulers probably governed through networks of local chiefs.

Archaeology strengthens this impression. Hillforts such as Trusty’s Hill in Galloway, with its Pictish-style carvings but Brythonic context, show a society both defensive and artistic. Early Christian carved stones, such as those at Bewcastle and Ruthwell, likewise blend local Brythonic tradition with wider Insular art.

Cumbria’s Distinct Identity

What emerges is a kingdom with a strong sense of itself as Cymric. Its language tied it to Wales, its saints to the wider Celtic church, its poets to a heroic tradition, and its society to kinship law familiar across the Brythonic world.

Yet Cumbria was also distinct: a northern frontier Brythonic kingdom, resilient and adaptive, balancing its traditions against the pressures of Angles, Picts, Gaels, and Norse.

In the next section, we turn to Cumbria’s kings and wars - the struggles that defined its survival for centuries against the might of neighbours.

Part III – Kings and Wars

Cumbria on the Battlefield

From its very beginnings, Cumbria was forged in conflict. It occupied a liminal zone - north of the Anglo-Saxons, south of the Picts, west of the Anglian kingdom of Bernicia, and open to Norse raiders across the sea. To survive here was to fight, and the chronicles and legends of the Old North are dominated by battles.

Arfderydd (Arthuret), 573

One of the most famous conflicts associated with Cumbria is the battle of Arfderydd, near modern-day Carlisle. Fought in 573, it was less a clash with outsiders than a civil war among the Britons themselves.

The causes are obscure, but later Welsh triads remember it as one of the “three futile battles of Britain.” Tradition says that Myrddin Wyllt (later remembered as Merlin) fought here, saw his comrades slaughtered, and in his grief and madness fled to the Caledonian forest. There he became the wild prophet of later legend.

The memory of Arfderydd demonstrates two truths about Cumbria: that Brythonic unity was fragile, and that its struggles generated myths that would shape all later British folklore.

The Carron and the Scots

A century later, in the early 7th century, the battle of the Carron pitted the Scots under Domnall Brec against the Brythons of Cumbria. A contemporary source described it as a “desperate conflict” in which Domnall was slain and the Brythons victorious. The fertile valley of the River Carron became a contested frontier, described by Ossianic verse as rolling “in blood.”

This episode shows that Cumbria was no minor player: it could defeat a Scottish king on his own ground. But it also reveals the ceaseless wars that characterised the region, with Cumbria caught between Scots, Angles, and Picts.

The Battle of Chester, 616

A pivotal moment came with the battle of Chester, fought between the Northumbrians and a coalition of Britons. The result was disastrous for the latter. The Angles cut Cumbria and Wales apart, severing the cultural lifeline between the Cumbrians and their southern kin. From then on, Cumbria faced north and west, isolated from the rest of the Cymry.

Yet even in isolation, Cumbria endured. Its kings maintained their courts, and its poets continued to sing.

Kings of the Old North

The annals and poetry preserve the names of several rulers who defined Cumbria’s story.

- Urien of Rheged: Though often associated with a neighbouring kingdom, Urien was a key figure in the defence of the Old North. Celebrated by the bard Taliesin, he fought the Angles with distinction. His son Owain ap Urien also appears in heroic poetry, later absorbed into Arthurian romance.

- Rhydderch Hael (“the Generous”): A king of Alt Clut (Dumbarton) remembered as a patron of St Kentigern. He embodied the link between religion and kingship in Cumbria.

- Kings of the Cumbrians (10th–11th centuries): Even as Anglo-Saxon England expanded, we find references to kings “of the Cumbrians.” These rulers entered alliances, sometimes with the Scots, sometimes with the English, to preserve their autonomy.

One chronicler noted that “in 945 Edmund, king of the English, laid waste all Cumbria and gave it to Malcolm of the Scots.” Yet even after this devastation, Cumbric rulers re-emerged, suggesting remarkable resilience.

Warfare and Identity

Cumbria’s wars were not only about survival. They were also about identity. Each battle reinforced the sense of the Cumbrians as distinct from their neighbours - neither Saxon, nor Scot, nor Pict, but Cymric.

Even in defeat, their memory was preserved in song. Aneirin’s Y Gododdin laments the slaughter of Brythonic warriors at Catraeth (Catterick), some of whom may have come from Cumbria. The heroic death of these warriors was remembered as proof of their loyalty to the Cymric cause.

The Long Struggle

By the late 9th and 10th centuries, Cumbria faced new enemies: Norse settlers, who brought Scandinavian place-names ending in -by, -thwaite, and -beck. These overlapped with Cumbric and Anglian names, producing the palimpsest of toponyms we see today.

Despite this, Cumbria retained a political identity into the 11th century. Kings of the Cumbrians are still named in chronicles at this date, ruling a land that was by then squeezed between Scotland, England, and Norse Dublin.

A Kingdom of Survival

Cumbria’s kings may not have commanded vast armies, but their ability to endure for centuries amid such pressures is extraordinary. Their story is one of resilience: a small Cymric kingdom holding out against the tide of conquest, long after others had fallen.

In the next section, we will explore how Cumbria’s myths and legends - Arthur, Merlin, and the prophetic tradition - intertwine with its decline and legacy.

Part IV – Myths, Decline, and Legacy

Arthur in the North

The legend of King Arthur is often associated with Cornwall or Wales, but many scholars of the 19th and early 20th centuries argued that Arthur’s true stage was the Old North - Cumbria, Strathclyde, and southern Scotland.

Archaeological journals noted that Arthur was “unquestionably a Brythonic hero, probably in particular a Cimbric hero, for the scenes of his chiefest activities are laid in Cumbria, in Cambria, and in Cornwall.” This perspective places Arthur not in the far southwest but firmly in the Cymric north.

- Mount Badon, the great victory that held back the Saxons for a generation, has been placed by some near Falkirk rather than Bath.

- Camlann, Arthur’s final battle, is sometimes identified with Camelon, a Roman fort close to Cumbria’s northern edge.

- Place-names across the region - Arthur’s Seat (Edinburgh), Arthur’s Table (Penrith), Arthurstone (Angus) - anchor his presence in the landscape.

Rather than a single historical warlord, Arthur may reflect the collective memory of Cumbric resistance against Saxon advance. His legend, preserved in Wales and Cornwall, may have originated in the desperate wars fought in the lands of Cumbria.

Merlin and the Prophetic Tradition

Alongside Arthur stands Merlin - or rather, Myrddin Wyllt, a Cumbrian figure. After the slaughter at Arfderydd in 573, tradition says Myrddin went mad, fled into the woods, and lived as a wild man, speaking in riddles and prophecies. Later writers merged him with the figure of Ambrosius to create the Merlin of Arthurian romance.

But the core story - a Brythonic warrior traumatised by civil war - belongs to Cumbria. His prophecies, remembered in Welsh poetry, imagine a time when the Cymry of the Old North would rise again. In this way, Merlin embodies both the tragedy and the enduring hope of Cumbria.

Folklore and Local Legends

Other legends clustered in the Borders preserve echoes of Cumbric memory. The tale of Fair Maid Lilliard, slain at Ancrum Moor in the 16th century, almost certainly echoes earlier Brythonic warrior traditions of female fighters. Place-names like Lilliot Cross and Lilliard’s Edge suggest continuity of memory.

Similarly, Ossianic poetry invokes the River Carron as a place of bloodshed where “the sons of battle are fled; the noise of war is not seen on our fields.” Such verses connect the physical landscape to layers of Brythonic and Gaelic memory, where Cumbria is always central.

The Decline of Cumbria

By the 10th century, Cumbria was surrounded on all sides:

- Angles of Northumbria to the east, pressing steadily westward.

- Scots to the north, absorbing Strathclyde into their kingdom.

- Norse settlers along the coast, whose byres, thwaites, and becks still mark the map.

The decisive moment came in 945, when King Edmund of England “laid waste all Cumbria and gave it to Malcolm of the Scots.” Yet even then, the Cumbrians re-emerged, still maintaining their own rulers into the late 11th century.

It was only with the Norman Conquest and the subsequent integration of the north into Anglo-Norman administration that Cumbria ceased to exist as a political entity.

Survival in Language and Place

Though Cumbric died out as a spoken language by the 12th century, it survived in fragments. The shepherds’ numerals (yan, tyan, tethera, methera, pimp) are perhaps the most famous. Place-names preserve dozens of Cumbric roots. Even dialect words in modern Cumbrian speech may be survivals.

These echoes remind us that Cumbria did not vanish overnight. Its culture seeped into the fabric of northern Britain, overlaid but not erased by later tongues.

Victorian Rediscovery

In the 19th century, Cumbria became the subject of fascination. Antiquarians debated whether Galloway was Pictish, Gaelic, or Brythonic; lectures at societies like the Menai Institute emphasised the survival of Kymry north of the Wall; reviews of scholars such as Seebohm and Kenneth Jackson highlighted the endurance of the Cumbric tongue.

Though romanticised, this rediscovery placed Cumbria firmly back into the story of Britain - not as a forgotten margin but as a central player in the island’s early medieval history.

The Legacy of Cumbria

Cumbria may never have been a great empire, but its endurance was remarkable. For centuries, it held out as a Cymric kingdom amid overwhelming odds. Its kings patronised saints and poets; its warriors fought battles whose memory outlasted them in song; its language lingered in names and rhymes; its myths gave Britain Arthur and Merlin.

To walk the hills of Cumbria today is to tread a palimpsest: Norse becks and thwaites layered over Brythonic pens and caers. Beneath every place-name, a Cumbric voice still whispers.

The story of Cumbria is the story of survival. It shows that history is not only written by the conquerors but remembered through the resilience of those who resisted. In Cumbria, history and legend are inseparably entwined - a kingdom both real and mythical, both lost and enduring.

The ancient Cymric kingdom of Cumbria stood at the crossroads of Britain’s early medieval world. Born from the ruins of Rome, sustained by its Brythonic language and culture, defended by its kings and warriors, and immortalised in its myths, Cumbria shaped the landscape of British history.

Its memory lives on not only in chronicles and place-names but in the stories that still capture our imagination. Arthur, Merlin, and the “Old North” are not merely legends - they are echoes of Cumbria, the Cymric kingdom that refused to be forgotten.

Related Articles

4 October 2025

The Ancient Blood: A History of the Vampire27 September 2025

Epona: The Horse Goddess in Britain and Beyond26 September 2025

Witchcraft is Priestcraft: Jane Wenham and the End of England’s Witches20 September 2025

The Origins of Easter: From Ishtar and Passover to Eggs and the Bunny12 September 2025

Saint Cuthbert: Life, Death & Legacy of Lindisfarne’s Saint7 September 2025

The Search for the Ark of the Covenant: From Egypt to Ethiopia5 September 2025

The Search for Camelot: Legend, Theories, and Evidence1 September 2025

The Hell Hound Legends of Britain25 August 2025

The Lore of the Unicorn - A Definitive Guide23 August 2025

Saint Edmund: King, Martyr, and the Making of a Cult14 August 2025

The Great Serpent of Sea and Lake11 August 2025

The Dog Days of Summer - meanings and origins24 June 2025

The Evolution of Guardian Angels19 June 2025

Dumnonia The Sea Kingdom of the West17 June 2025

The Roman Calendar, Timekeeping in Ancient Rome14 June 2025

Are There Only Male Angels?