Written by David Caldwell ·

Epona: The Horse Goddess in Britain and Beyond

Part I. Origins and Roman Adoption

Epona, the horse goddess of the Celts, is one of the few native deities of the Western provinces to have been fully embraced by Rome. Her name itself derives from the Gaulish epo- (horse), with her role firmly anchored in the relationship between humans and horses. Unlike most Celtic gods, whose worship was highly localised, Epona’s cult spread far and wide - from Gaul to the Danubian provinces, and even into Rome itself, where dedications in her honour were set up in the heart of the Empire.

In Britain, the earliest scholarly notices - such as an 1886 issue of The Tablet - remark on her unique position as a Celtic goddess who was not only tolerated but celebrated in Rome. Roman cavalry, dependent on their mounts for prestige and survival, were among her most dedicated worshippers. Epona became a divine patron of horses, stables, and riders, invoked to protect both animal and soldier alike. That she is so often depicted feeding or nurturing horses suggests a figure who mediated between human need and animal vitality. The Romans, practical in their religious syncretism, took her into their pantheon without erasing her Celtic essence.

Part II. Inscriptions, Altars, and Shrines

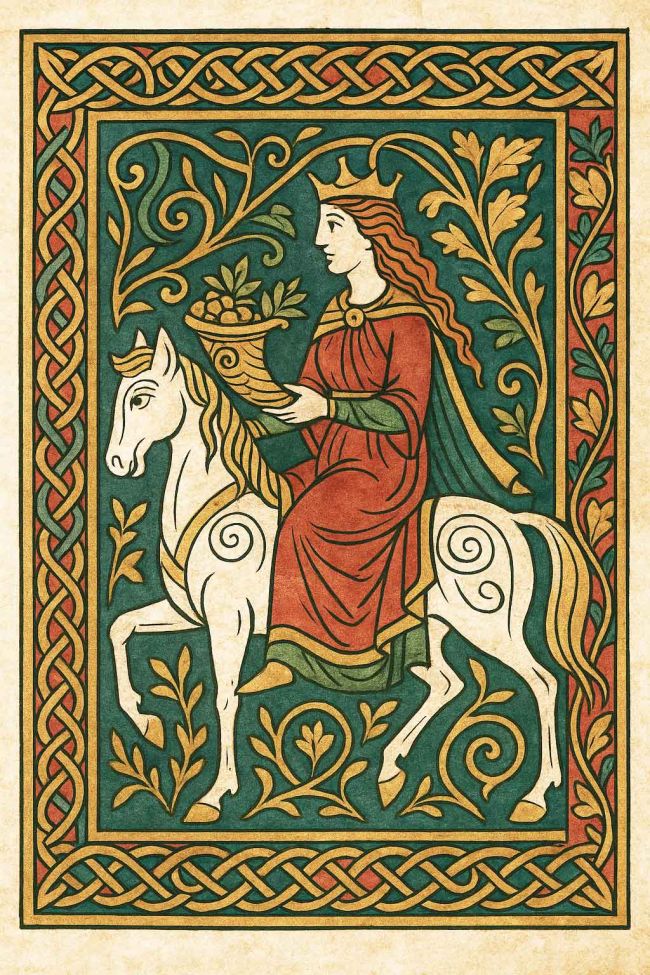

Epona’s cult is one of the best documented among Romano-Celtic deities because of the sheer number of inscriptions and altars dedicated to her. Carvings often show her seated, sometimes side-saddle, surrounded by horses or foals - a striking departure from Roman goddesses, who were rarely depicted in such intimate contact with animals.

A 1925 article in the Western Morning News noted discoveries of inscribed stones to Epona across Gaul and Britain, emphasising her status as a goddess ‘of the people’ as well as of the military. Inscriptions have been found at sites such as Chester and Caerleon, both key cavalry bases. At these shrines, Epona was invoked for fertility, prosperity, and safe travel. The Oban Times in 1954 noted her prominence in northern Britain, where Roman and Celtic traditions interwove, suggesting that her worship adapted easily to frontier life.

What sets her apart is the breadth of her following. Dedications to Epona were made not only by cavalrymen but also by civilians - horse-breeders, merchants, even women. This universality hints at a deity who transcended narrow cult boundaries. She was not only about war or trade but about the deep, daily reliance humans placed on horses.

Part III. Horses, Myth, and Sacrifice

Epona’s cult was not only expressed through inscriptions and dedications but also through acts of ritual devotion that bound horses and humans in sacred relationship. Archaeology across Roman Britain offers hints that equine sacrifice sometimes formed part of these rites.

An excavation at Chelmsford, reported in the Billericay Gazette (1987), revealed the skeleton of a young horse carefully deposited in a pit dating from the 2nd century. The context pointed not to butchery but to ritual. Such offerings were not isolated: classical sources also describe the ritual burial of horses among Celtic peoples, often linked to kingship and divine renewal. The white horse, in particular, carried associations with sovereignty and vitality - traditions that echo faintly in chalk hill figures and May Day ‘hobby horse’ parades.

Local legends of spectral horsemen and protective carved heads, linking them with Odin’s Sleipnir and Epona. What emerges is the horse as mediator between realms - in battle, in ritual, and in folklore. Epona presided over them all.

Part IV. Celtic Roots and Linguistic Echoes

Though her cult flowered most visibly in Gaul and Rome, Epona’s roots run deep into the Celtic-speaking world of Britain and Ireland. She does not appear by name in the Mabinogion, yet her shadow can be felt in figures like Rhiannon, the mysterious horse-goddess of Welsh myth. Rhiannon first enters the tales riding a supernatural horse no man can overtake. Later, as punishment, she is forced to carry visitors on her back - a humiliation that betrays her equine ties.

The Western Mail (1930) dismissed the idea of Rhiannon as an ‘equine goddess’ as overstated, yet conceded the association. In Ireland, parallels can be drawn with Macha and the ritual horse-sacrifices tied to kingship. The Merthyr Express (1939) noted how divine names, including Epona’s, survived in surnames like Leyshon. The Kilkenny Journal (1948) highlighted the ubiquity of horse-deities in Celtic religion, while the Scots Magazine (1929) connected her to witches’ cries of ‘horse and hattock.’ Through language, names, and folk-memory, Epona endured.

Part V. Stones, Symbols, and Archaeology

In stone and soil, Epona’s presence becomes tangible. Pictish carvings from the 7th to 10th centuries, surveyed in Country Life (1962), depict elegant ponies and women riding side-saddle. One stone at Hilton of Cadboll memorialised a woman of rank through her equestrian image, with bridles resembling La Tène Celtic bits. Such continuity suggests the sacred horse motif endured well into the Christian era.

In 1990, the Carluke and Lanark Gazette reported a horse burial at Eildon Hill, interpreted as a sacrifice perhaps offered to Epona. The Illustrated London News (1978) featured Celtic brooches adorned with horses, reminders that her protection was invoked in everyday ornaments. Through stones, burials, and portable symbols, she lived not as abstraction but as practical power.

Part VI. Folklore Survivals and Modern Memory

Even after Christianisation, Epona’s shadow lingered in British custom. The Illustrated London News (1975) identified the White Horse of Uffington as a possible cultic image of her, noting its Iron Age parallels. May Day ‘hobby horses,’ discussed in the Southport Visitor (1996), likely preserved fertility rites tied to her. The Coventry Evening Telegraph (1967) saw Lady Godiva’s naked ride as a survival of horse-goddess iconography. The North Wales Weekly News (1997) linked Epona to themes of health, protection, and liminality in Celtic culture.

The spectral horsemen of folklore, too, may echo her role as threshold guardian. In festivals, legends, and fears, Epona endured in disguise.

Part VII. Cultural Survivals: From Taboo to Pony

Though temples to Epona fell, cultural memory kept horses sacred. The taboo against eating horsemeat in Britain, one of the strongest in Europe, may stem from church bans on pagan horse-sacrifice, once offered to her. The horseshoe, a common luck-charm, carried both the apotropaic power of iron and Epona’s protective aura. Even our language carries her root: Latin Epona comes from Gaulish epo- (horse), the same root that gave rise to Welsh ebol (foal), Irish ech, and, via French poulain/poulenet, our word pony. Thus, every time the word is spoken, a trace of the Great Mare remains.

Conclusion: Epona’s Return

From Gaulish groves to Roman altars, from chalk horses to May Day streets, Epona has never fully vanished. She is the rare Celtic goddess absorbed by Rome, worshipped by soldiers and civilians alike, protector of horses and humans together. Her name survived in language, her cult in taboo, her image in folklore. Today, she remains an emblem of the sacred bond between human and animal, of feminine sovereignty, and of myth’s endurance. Epona still rides alongside us, unseen but never absent.

Related Articles

4 October 2025

The Ancient Blood: A History of the Vampire26 September 2025

Witchcraft is Priestcraft: Jane Wenham and the End of England’s Witches20 September 2025

The Origins of Easter: From Ishtar and Passover to Eggs and the Bunny12 September 2025

Saint Cuthbert: Life, Death & Legacy of Lindisfarne’s Saint7 September 2025

The Search for the Ark of the Covenant: From Egypt to Ethiopia5 September 2025

The Search for Camelot: Legend, Theories, and Evidence1 September 2025

The Hell Hound Legends of Britain25 August 2025

The Lore of the Unicorn - A Definitive Guide23 August 2025

Saint Edmund: King, Martyr, and the Making of a Cult14 August 2025

The Great Serpent of Sea and Lake11 August 2025

The Dog Days of Summer - meanings and origins24 June 2025

The Evolution of Guardian Angels19 June 2025

Dumnonia The Sea Kingdom of the West17 June 2025

The Roman Calendar, Timekeeping in Ancient Rome14 June 2025

Are There Only Male Angels?