Written by David Caldwell ·

From Synagogue to Empire: How Saint Paul Turned the Jewish Church into the Roman Church

Prologue: The Pharisee of Tarsus

Our earliest image of Saint Paul is not of an apostle, but of a persecutor.

Before he became the missionary of Christ, he was Saul of Tarsus, a Jew of the Second Temple era, steeped in the Law and proud of his lineage.

Born in Cilicia, in the Greco-Roman city of Tarsus, Saul inherited both Pharisaic piety and Roman privilege - a rare combination that would shape his destiny.

He would later remind his accusers:

“I am a Jew, born in Tarsus, brought up in this city, taught at the feet of Gamaliel, according to the strict manner of the law of our fathers.”

(Acts 22:3)

Tarsus was no provincial town. It was a centre of Hellenistic learning, home to Stoic philosophers and Eastern mystics.

There, Saul learned Greek rhetoric and argument - skills that would one day make his letters the backbone of Western theology.

At Jerusalem, he studied under Rabban Gamaliel, the most celebrated teacher of the Law, absorbing the discipline of the Pharisees - those whom Josephus called “the most exact interpreters of the ancestral customs.”

His family, though Jewish, were Roman citizens - likely a privilege earned by an ancestor who had served or traded with the Empire. This gave Saul unusual freedom: he could move safely across provinces, appeal to Roman law, and speak in the tongue of philosophers.

In him, the worlds of Moses and Caesar, synagogue and forum, met.

The Persecutor of The Way

The first followers of Jesus called their movement The Way - a sect within Judaism that still worshipped in the Temple and kept the feasts, believing the Messiah had come.

To Saul, they were dangerous heretics undermining the Law.

It was with his approval that Stephen, the first Christian martyr, was stoned to death.

“And Saul was consenting unto his death.” (Acts 8:1)

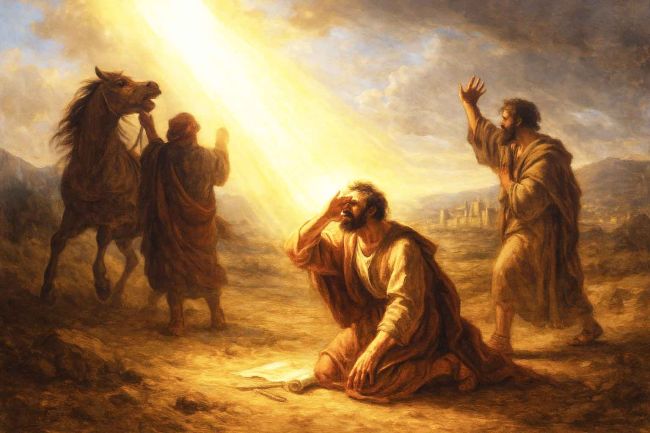

Armed with letters from the high priest, Saul set out for Damascus to arrest more of “this way.”

It was on that journey - an official mission of suppression - that he was stopped, literally and spiritually, in his tracks.

“As I journeyed,” he told King Agrippa,

“I saw a light from heaven, above the brightness of the sun, and I heard a voice saying unto me, ‘Saul, Saul, why persecutest thou me?’”

(Acts 26:13–14)

That question pierced deeper than rebuke - it was self-revelation.

In persecuting others, Saul had been resisting his own conscience.

As the voice continued, “It is hard for thee to kick against the pricks,” the proud Pharisee was confronted by the limits of his own certainty.

Blinded for three days, he entered Damascus a captive rather than conqueror.

When the disciple Ananias laid hands upon him and restored his sight, Saul’s vision - both literal and moral - was forever changed.

He was baptised and took the Roman name Paul, symbol of his new universal calling.

He was not merely converted; he was repurposed.

Everything that had made Saul dangerous to the early Church now made Paul indispensable to its survival.

He could debate with rabbis, reason with Stoics, and plead with governors.

He spoke the languages of faith, philosophy, and empire.

I. The Forgotten Jewish Church

Before Christianity became the religion of Rome, it was a sect of Jerusalem.

The first believers were Jews who prayed in the Temple, observed the feasts, and read the Torah.

As The Jewish World wrote in 1877:

“The primitive Christians were, in every respect, Jews. They read the same scriptures, observed the same feasts, and prayed toward the same holy place. The only difference was their belief that the Messiah had already come.”

Their leader in Jerusalem was James the Just, the brother of Jesus - a man who never ceased attending the Temple and who, according to Hegesippus, was revered even by non-believing Jews.

They called their fellowship The Way and expected the imminent restoration of Israel.

For them, Jesus was the fulfilment, not the abolition, of Jewish hope.

It was Paul, not Peter or James, who changed that trajectory.

II. The Pharisee Who Changed Everything

Saul of Tarsus became Paul the Apostle - and with him, Christianity turned outward.

His mission, born from vision, carried him from Antioch to Corinth, from Philippi to Ephesus, and ultimately to Rome itself.

“Unto me, who am less than the least of all saints, is this grace given, that I should preach among the Gentiles the unsearchable riches of Christ.” (Ephesians 3:8)

His first act in any new city was to visit the synagogue, reasoning with the Jews that Jesus was the promised Messiah.

When rejected, he turned to the Gentiles:

“It was necessary that the word of God should first have been spoken to you; but seeing ye put it from you… lo, we turn to the Gentiles.” (Acts 13:46)

In that declaration, the faith of Israel became the faith of the Empire.

III. Synagogues, Shipwrecks, and Survival

Paul’s ministry was one of travel, conflict, and endurance.

He was beaten in synagogues, imprisoned in Philippi, and survived three shipwrecks - one on the coast of Malta, where he was bitten by a viper and survived.

The Cheltenham Examiner (1859) captured him well:

“A man who stretched his arms east and west, linking the Law with the Gospel. The fiery zeal of the Jew, the logic of the Greek, and the practical energy of the Roman met in him.”

By the time he reached Rome, chained as a prisoner, his letters had already begun to bind the Church in a network stronger than any empire.

IV. Josephus and the Fall of Jerusalem

While Paul preached abroad, his homeland burned.

In 70 CE, Roman legions under Titus destroyed Jerusalem and the Temple.

The historian Flavius Josephus, himself a Pharisee, recorded the devastation:

“The Temple was set on fire against the will of Caesar. The hill itself seemed to boil up from its foundations, and the flames enveloped everything round about.”

For Judaism, this was apocalypse - the loss of God’s dwelling among His people.

For Paul’s followers, it was vindication: the proof that the covenant had moved from stone to spirit.

The Temple was gone, but the faith survived - portable, invisible, universal.

V. Nero’s Rome and the Birth of the Roman Church

Paul’s end came under Nero, who blamed Christians for the Great Fire of Rome.

Tacitus tells us they were “clothed in wild beasts’ skins and torn by dogs, or set on fire to serve as lamps at night.”

As a Roman citizen, Paul was spared crucifixion and executed swiftly by the sword near the Ostian Gate.

Peter, the fisherman, was crucified upside down.

In the catacombs of Nero’s city, survivors painted anchors, fish, and lambs - symbols of faith beneath empire.

Out of those tombs, the Church of Rome was born: persecuted, secretive, and already steeped in martyrdom.

VI. The Pharisees and the Remnant of Israel

After the fall, Judaism itself reorganised.

The Sadducees, tied to the Temple, vanished; the Essenes scattered.

Only the Pharisees endured - pragmatic scholars who founded new academies in Yavneh under Rabban Yohanan ben Zakkai, preserving the Law through study and prayer.

Where Paul’s followers replaced sacrifice with faith in Christ, the rabbis replaced it with discipline and law.

Both were acts of survival.

As The Jewish World noted:

“Judaism, purified by fire, found strength in the Law; Christianity, born of the same flame, found strength in the Cross.”

VII. The Moment of Transformation: From Sect to System

Before Paul, the followers of Jesus were a small, fractured movement.

After him, they were a network - structured, literate, and missionary.

The shift was not spontaneous; it was Paul’s design, aided by the machinery of the Roman world.

His letters - written to communities he founded and revisited - became the first connective tissue of Christian organisation.

They instructed, corrected, and standardised practice across provinces.

The synagogues became ekklesiai - assemblies - a term borrowed from Greek civic life.

When the Council of Jerusalem (c. 49 CE) accepted Paul’s argument that Gentiles need not follow the Mosaic Law, the gates were thrown open.

Within a generation, Gentiles outnumbered Jews.

Greek replaced Hebrew; bishops replaced elders; the Eucharist replaced sacrifice.

What had been a messianic revival movement became a philosophical and theological system - one capable of surviving empire because it had learned to imitate it.

As one historian observed:

“What Rome achieved by the sword, Paul achieved by the word.”

VIII. Paul’s Transformation of the Faith

Paul’s genius - and his controversy - lay in his universalisation of the covenant.

Where the Law had been Israel’s bond with God, Paul made faith the bond of all humanity.

“For by grace are ye saved through faith, not of works, lest any man should boast.” (Ephesians 2:8–9)

This was not merely theology - it was identity.

The God of Abraham became the God of all nations; the Messiah of Israel became the Redeemer of the world.

As The Jewish World phrased it:

“In the space of a single generation, the faith of the synagogue had become the faith of the forum.”

But in severing Christianity from its Jewish roots, Paul also changed its nature.

He replaced the living teachings of Jesus with the doctrine of Christ.

IX. Christ the Martyr and the Lost Teacher

Paul did not preach the parables; he preached the crucifixion.

His message was not “Follow His teachings,” but “Believe in His resurrection.”

The moral gospel of Galilee became a theology of blood and redemption.

Friedrich Nietzsche, writing in The Antichrist, saw in this the moment of betrayal:

“Jesus brought the good news - and Paul the bad. Jesus died too soon; had he lived longer, he would have denied the Church founded in his name.”

For Nietzsche, Paul transformed a message of inner freedom into one of guilt and obedience - “Platonism for the masses,” he called it.

Yet it was precisely this reinterpretation that ensured survival.

A teacher can be forgotten; a martyr can be worshipped.

X. From Jerusalem to Rome

By the end of the first century, the transformation was complete.

The Church of James, which had prayed in Hebrew and faced Jerusalem, had vanished.

In its place stood the Church of Rome, writing in Latin, modelled on the Empire it once defied.

Josephus had chronicled the fall of the Temple as a historian;

Paul had interpreted it as a theologian.

Between them lies the hinge of history - the moment when faith escaped its birthplace and took root in the world.

XI. The Hinge of History

The story of Paul is the story of Christianity itself:

how a sect of Jewish mystics became the religion of emperors.

He began as a persecutor of the Law and ended as its most famous interpreter.

He carried the name of Jesus from the synagogues of Judea to the courts of Caesar.

He turned a movement of repentance into a creed of redemption - a rabbi’s message into the mythos of Christendom.

“In less than a century,” wrote The Jewish World,

“the Church that had prayed in the Temple of Jerusalem was praying in the catacombs of Rome.”

That transformation - from scroll to creed, from covenant to empire - is the hinge upon which Western history turns.

And it turned upon one man:

the Jew of Tarsus, the citizen of Rome, the apostle of faith, and the architect of Christendom.

Epilogue: The Lost Voice

Would Jesus have recognised Paul’s Church as his own?

The historical Jesus was a Second Temple Jew - a teacher of moral renewal, not metaphysics.

He prayed in the Temple, argued with Pharisees, and spoke of the Kingdom of God as something near, not celestial.

His brother James, remembered by Josephus but not by Paul, continued that path - a faith within Judaism, not outside it.

But Paul’s gospel eclipsed James’s.

Where James preached justice, Paul preached grace.

Where Jesus offered a way of life, Paul created a system of belief.

Between the two lies Christianity’s central disjoint - the shift from a moral teacher’s voice to a theological empire’s creed.

Whether that change was revelation or revolution remains the unhealed question at the heart of the faith:

that the voice of Jesus still echoes within a Church that speaks, unmistakably, in the language of Paul.

Related Articles

12 October 2025

Queen of Heaven: From the Catacombs to the Reformation4 October 2025

The Ancient Blood: A History of the Vampire27 September 2025

Epona: The Horse Goddess in Britain and Beyond26 September 2025

Witchcraft is Priestcraft: Jane Wenham and the End of England’s Witches20 September 2025

The Origins of Easter: From Ishtar and Passover to Eggs and the Bunny12 September 2025

Saint Cuthbert: Life, Death & Legacy of Lindisfarne’s Saint7 September 2025

The Search for the Ark of the Covenant: From Egypt to Ethiopia5 September 2025

The Search for Camelot: Legend, Theories, and Evidence1 September 2025

The Hell Hound Legends of Britain25 August 2025

The Lore of the Unicorn - A Definitive Guide23 August 2025

Saint Edmund: King, Martyr, and the Making of a Cult14 August 2025

The Great Serpent of Sea and Lake11 August 2025

The Dog Days of Summer - meanings and origins24 June 2025

The Evolution of Guardian Angels19 June 2025

Dumnonia The Sea Kingdom of the West17 June 2025

The Roman Calendar, Timekeeping in Ancient Rome14 June 2025

Are There Only Male Angels?