Written by David Caldwell ·

Witchcraft is Priestcraft: Jane Wenham and the End of England’s Witches

Part I: Witchcraft is Priestcraft

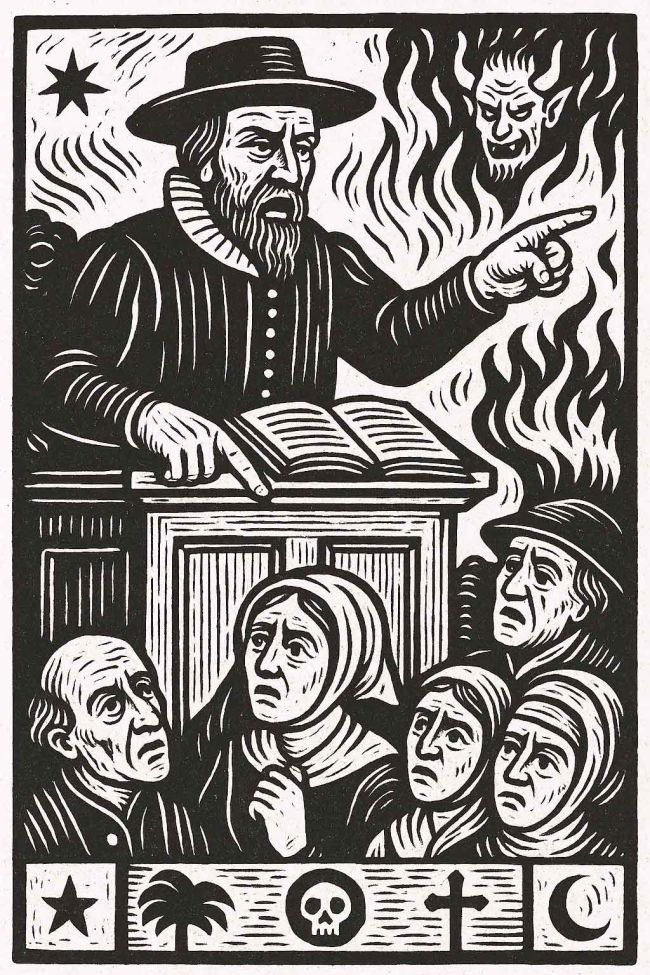

When the witch trials of early modern Europe are examined, one phrase cuts to the heart of the matter: “Witchcraft is Priestcraft.”

It means that witches were not simply “discovered” by their neighbours, but created by the clergy. Through sermons, scripture, and legal testimony, ministers turned suspicion into doctrine and fear into punishment. A skilled clergyman could inflame religious fervour, and in doing so, elevate his own authority at the expense of vulnerable members of society.

The Biblical foundation for centuries of persecution rested on two verses:

- Exodus 22:18 - “Thou shalt not suffer a witch to live.”

- Leviticus 20:27 - “A man also or woman that hath a familiar spirit, or that is a wizard, shall surely be put to death.”

These lines, cited endlessly from pulpit and courtroom, gave witchcraft prosecutions their sacred sanction. To question them was to question God’s word itself. From the Inquisition in Catholic Europe to Puritan ministers in New England, scripture was the weapon that made witches real.

And yet, by the dawn of the eighteenth century, a new voice was emerging - one that doubted not just the existence of witches, but the integrity of those who preached them into being.

At the centre of this turning point stands Jane Wenham of Walkern, Hertfordshire: the so-called last witch of England.

Part II: The Trial of Jane Wenham

In 1712, Jane Wenham was dragged before the Hertford Assizes, accused of bewitching her neighbours. The charges were familiar: livestock sickened, children fell into fits, milk curdled. A quarrel over straw with a local farmer sparked renewed suspicion, and soon the village buzzed with whispers of witchcraft.

At her trial, ministers and villagers alike offered lurid testimony. She was said to mutter curses, to change her voice at will, even to fly through the air. Pins stuck into her arms drew no blood. One witness swore she had been seen riding on the Devil’s back.

But when the case reached Justice Sir John Powell, something remarkable happened. As the jury nodded along with the old formulas of fear, Powell pushed back. “There is no law against flying,” he remarked dryly. Nor against broomsticks, nor against muttered prayers.

Despite his scepticism, the jury convicted Wenham. She was sentenced to death.

And then the true shift revealed itself. Powell refused to enforce the sentence. He secured a reprieve, and through the influence of Colonel Plumer of Gilston and the Cowper family, Wenham was pardoned.

The clergymen had done their best to conjure a witch into existence. But the law - now influenced by Enlightenment doubt - would not oblige them.

Jane Wenham lived on until 1730, supported in charity, and was buried at Hertingfordbury. The Hertford Mercury (1888), looking back, described her funeral as “decent” and noted she had been remembered more as a victim than a villain.

In that moment, the balance tipped. Witchcraft, once upheld by priestcraft, was unmade by law and reason.

Part III: The Impossibility of Witchcraft

The most remarkable response to Jane Wenham’s trial came in the form of a pamphlet printed in London in 1712: *The Impossibility of Witchcraft: plainly proving, from Scripture and Reason, that there never was a witch; and that it is both irrational and impious to believe there ever was.* It did more than mock the depositions - it dismantled the very idea of witchcraft.

The anonymous author ridiculed the charges brought against Wenham as laughable nonsense:

“…the trial of one Jane Wenham, a reputed witch, whom that enemy to superstition, the very worshipful Sir Henry Chauncy, gravely committed, without laughing, to Hertford gaol; where she was tried and found guilty (against the judge’s will) of conversing with the weevil in the shape of a cat, making a maid that could not walk without leading leap over a five-bar gate, and run as swift as a greyhound, with several other incredibles.”

The writer then set out a systematic demolition of witchcraft belief. First, he argued, witches do not exist in scripture at all:

“I have, in the first place, shown, that there is no such thing as a witch in Scripture. Secondly, that it took its beginning from heathen fables. Thirdly, that it was afterwards improved by papal impostures. In the fourth place, I have produced several arguments against the affirmers of witchcraft… Lastly, I have endeavoured to show by what means this opinion of witches came into the world.”

One of the pamphlet’s most striking moves was to expose errors in Bible translation. Words that had been read as “witch” were, in Hebrew and Greek, quite different.

From this, the author concluded that witchcraft was not divine truth but human invention - the work of “miracle-mongers” and priests who sought to deceive the people.

The pamphlet reframed witchcraft entirely: not a supernatural crime, but a symptom of priestcraft - a manipulation of scripture, superstition, and authority. In doing so, it turned Jane Wenham’s trial from the end of an old age into the beginning of a new one.

Part IV: Repeal and Enlightenment (1735 Act)

Jane Wenham’s reprieve did not instantly silence the machinery of priestcraft, but it revealed its weakness. The law had begun to shift. Within a generation Parliament would go further still: it would repeal the witchcraft statutes outright.

For nearly two centuries, the laws of Henry VIII, Elizabeth I, and James I had empowered clergy and magistrates to hunt witches with biblical certainty. These statutes gave Exodus and Leviticus the weight of English law. But in 1735, the tide of Enlightenment scepticism broke over Westminster.

The Derby Mercury of 4 March 1735 reported the debate: “…that the persons pretending to exercise Witchcraft, or discovering stolen goods by pretended science, being lawfully convicted thereof, shall suffer imprisonment for a whole year, without bail or mainprize, and shall stand in the pillory once in every quarter.”

The language is striking. Witchcraft was no longer a crime against God but a kind of imposture - a trick, a fraud upon the gullible. The penalty was no longer death but public shame.

This was not just a legal reform. It was a cultural revolution. What had once been divine command was now dismissed as error - or worse, as clerical manipulation. The very phrase “witchcraft is priestcraft” summed up the shift: witches existed only because priests said they did.

After 1735, England stood apart. The statutes were gone. Witches, in law at least, no longer existed.

Part V: Britain Looks Abroad

With the statutes repealed, witchcraft in Britain passed from legal terror to cultural curiosity. The old fears became material for satire, pamphleteering, and moral lessons.

By the 1730s and 1740s, English newspapers reported witchcraft cases not at home but abroad. The Gloucester Journal of 24 August 1731 relayed stories from Russia, where peasants still trusted in charms and spells. Reports from Hungary told of victims burned or drowned on the flimsiest of suspicions.

To English readers, such tales became evidence of their own nation’s progress. Witchcraft was something other countries believed in - not enlightened Britain.

At home, the language of witchcraft was increasingly applied to imposture and entertainment. Haunted houses in London, reported in the Kentish Weekly Post in 1740, drew fascinated crowds until exposed as pranks. The humour lay not in the tricks themselves but in the credulity of those who still believed.

Across the Atlantic, however, the word “witchcraft” still carried its older weight. The Kentish Weekly Post of 7 September 1743 printed a letter from New England complaining of revivalist preachers whose congregations fell into trances and convulsions. Critics called it “a spiritual witchcraft” - explicitly recalling Salem only half a century earlier.

Thus the vocabulary survived, but its meaning had shifted. In Britain, witchcraft was fraud, imposture, or foreign ignorance. In America, it was a way to describe religious excess.

And in Hertfordshire, the memory of Jane Wenham lingered. Not as a sorceress, but as the last flicker of a darkness England had now chosen to leave behind.

Part VI: The Victorian View

By the nineteenth century, witchcraft was no longer a living terror in Britain. It had become a subject for antiquarians, folklorists, and journalists to pick over with equal parts fascination and moral distance. The language of Enlightenment - reason versus superstition - coloured every retelling.

A particularly vivid example appeared in Public Opinion on 26 April 1895, under the headline Witches and Witchcraft. The article surveyed stories from across Europe and beyond, astonished at how stubbornly the belief had survived.

From Paris came tales of a clerk invoking “the literal devil and all his works” in his ledgers. From Moscow, superstitions that the blood of a pregnant woman could render thieves invisible. From Ireland, the harrowing story of a woman accused of witchcraft by her own family, with priests and neighbours demanding she be tried by fire.

The article also looked back at Europe’s bloody record. Geneva’s last witch, Michei Chauderon, was strangled and burned in 1652, after doctors “proved” her guilt by laying a dead serpent on her body. In France, the blind ferocity of belief had continued into the late seventeenth century.

Turning to England, Public Opinion rehearsed the familiar chronology: the first trial in 1209; the mass hangings under Matthew Hopkins in 1645; the last major prosecution, Jane Wenham in 1712; and the shadowy suggestion that Mary Hicks and her daughter may have been executed as late as 1716.

The article’s conclusion was clear. Witchcraft belonged to the past, a grim theatre of superstition that Enlightened Britain had outgrown. And yet, its persistence abroad - and in rural corners of Ireland - reminded Victorians that the line between reason and credulity was never as firm as they liked to imagine.

Part VII: The Memory of Jane Wenham

Even so, Jane Wenham herself was not forgotten. Her story lived on in county histories, antiquarian collections, and local memory.

The Hertford Mercury in 1888 described her funeral as “decent,” noting that she died around 1729 or 1730 and was buried at Hertingfordbury. Far from the monstrous figure of sermons, she had become a figure of pity.

Later retellings sharpened the moral. The Citizen of Letchworth, writing in 1910, framed Wenham’s case as proof of how “ignorance and superstition” could be inflamed into cruelty by clerical zeal. Sir Walter Scott, in his Letters on Demonology and Witchcraft, echoed the point: dissenting ministers had pressed hardest for her conviction, while the more moderate voices of the established church showed restraint.

Above all, the phrase that haunted her memory was the one that had crystallised in eighteenth-century pamphlets and lingered in nineteenth-century commentary: “Witchcraft is priestcraft.”

It was never truly about Jane Wenham’s muttered prayers, or her neighbour’s curdled milk, or the quarrel over straw that sparked her downfall. It was about the authority of the pulpit, and the power of ministers to conjure witches into being by turning scripture into accusation.

And it was about the moment when that power faltered - when Sir John Powell could look over the depositions, hear the wild tales of flying, muttered curses, and pins that drew no blood, and declare with dry finality: “There is no law against flying.”

From then on, Wenham’s story stood not as a tale of sorcery but as a parable of power - how it was abused, and how, at last, it was undone.

Related Articles

4 October 2025

The Ancient Blood: A History of the Vampire27 September 2025

Epona: The Horse Goddess in Britain and Beyond20 September 2025

The Origins of Easter: From Ishtar and Passover to Eggs and the Bunny12 September 2025

Saint Cuthbert: Life, Death & Legacy of Lindisfarne’s Saint7 September 2025

The Search for the Ark of the Covenant: From Egypt to Ethiopia5 September 2025

The Search for Camelot: Legend, Theories, and Evidence1 September 2025

The Hell Hound Legends of Britain25 August 2025

The Lore of the Unicorn - A Definitive Guide23 August 2025

Saint Edmund: King, Martyr, and the Making of a Cult14 August 2025

The Great Serpent of Sea and Lake11 August 2025

The Dog Days of Summer - meanings and origins24 June 2025

The Evolution of Guardian Angels19 June 2025

Dumnonia The Sea Kingdom of the West17 June 2025

The Roman Calendar, Timekeeping in Ancient Rome14 June 2025

Are There Only Male Angels?