Written by David Caldwell ·

Mary Magdalene: disentangling the woman, the name, the number, and the place

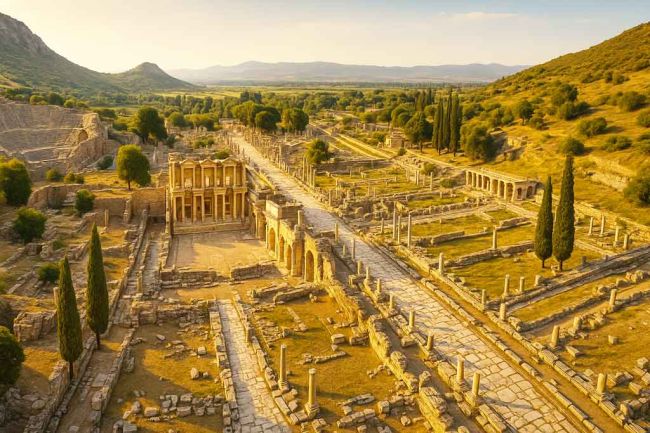

I set out to write about the “rehabilitation” of Mary Magdalene - the familiar correction that she was not the anonymous sinner of Luke 7. That story is worth telling, but as I walked through the sources a different question became more urgent: where did Mary Magdalene actually end her life? When you follow the oldest paths, they do not lead to Provence. They climb the hills behind the Roman theatre of Ephesus, pass a spring and a ruined chapel, and face the cave loved by late–antique pilgrims as the home of the Seven Sleepers. The Greek East remembered her there; Byzantine chroniclers said her relics were later moved to Constantinople. And that eastern memory, set in the very heart of the early church, helps us understand who she was, what “seven demons” meant, and why her name has been misunderstood for centuries.

This is the long view - woman, number, name, and place - told plainly and without the medieval haze.

The Gospel portrait: healed disciple, patron, first witness

The canonical picture is astonishingly clear when we let it speak.

- Her healing: Luke introduces her as “Mary, called Magdalene, from whom seven demons had gone out” (Lk 8:2). In biblical speech seven is the number of fullness; to say seven demons were expelled is to say she was completely afflicted and completely healed. It is not a moral smear; it is the measure of the cure.

- Her discipleship: Luke immediately adds that Mary was one of the women who travelled with Jesus and “provided for them out of their means.” She is not a bystander; she is part of the travelling mission, a patron with resources.

- Her presence at the passion: When many fell back, she stayed close (Mk 15:40; Jn 19:25). She saw where the body was laid (Mk 15:47).

- Her Easter: At dawn she came to anoint the body, found the tomb open, met the risen Christ, and carried the news. “I have seen the Lord” (Jn 20:18). For that, the Orthodox call her Equal to the Apostles; in the West she is often called apostle to the apostles. Her feast day is 22 July.

Scripture says nothing more about her later life. Beyond the Gospels we must read traditions - some ancient, some medieval - and weigh them.

Where she was from, and what “Magdalene” means

“Magdalene” is not a surname. It is a toponym: Mary from Magdala.

- Magdala lay on the western shore of the Sea of Galilee, just north of Tiberias. In Aramaic Migdal means “tower”; one local form, Migdal Nunayya, means “tower of fish,” which fits what we know of the district’s salt-fish industry in the Roman period (the Greek name Taricheae - “pickling works” - survives in Josephus).

- Her being “of Magdala” distinguishes her from other Marys and quietly suggests means. A woman capable of underwriting a travelling ministry was either independently resourced or a manager of family wealth. Nothing in the Gospels marks her as a sex worker; everything marks her as an engaged, generous disciple.

The persistent mistranslations

Two errors have clung to her name in popular retellings:

- “Magdalene” = plaited hair / hairdresser.

- A stray tradition misread a Talmudic phrase (megaddela se’ar nashaya - “dresser of women’s hair”) and connected it to Mary, as though “Magdalene” described her profession or hairstyle. It does not. The word is geographic. Patristic allegories sometimes played with “tower” (magdal turris) - Gregory the Great could call her a “tower” of devotion - but the philology is straightforward: from Magdala, not “of braids” and not a euphemism for a courtesan.

- “Magdalene” = woman of ill repute.

- This comes from the conflation (see below), not from the word. When Gregory the Great merged three women in a sermon - Luke’s anonymous sinner, Mary of Bethany, and Mary Magdalene - the association stuck in the Latin West. Language did the rest: over time “Magdalene” came to mean “repentant prostitute” in Western art and folklore. But that is late reception, not biography.

Why so many Marys - and how they were confused

“Mary/Miriam” was by far the most common women’s name among first-century Judeans. The New Testament gives us at least six distinct Marys:

- Mary, the mother of Jesus.

- Mary Magdalene.

- Mary of Bethany, sister of Martha and Lazarus.

- Mary of Clopas, likely the mother of James and Joses (also called “the other Mary”).

- Mary, mother of John Mark, whose house hosted the Jerusalem church (Acts 12:12).

- Mary of Rome, commended by Paul (Rom 16:6).

They cluster around the same events: multiple Marys stand near the cross, carry spices, and visit the tomb. Without surnames, later readers stitched narratives together. In A.D. 591 Pope Gregory the Great delivered a homily that explicitly identified the sinful woman of Luke 7 with Mary of Bethany and with Mary Magdalene. Medieval preaching and painting then fixed the Penitent Magdalene - long hair, jar of ointment, cave.

The Greek East never made that merger. There, Mary Magdalene is celebrated as Myrrhbearer and first witness; Mary of Bethany and the unnamed sinner remain other women. From the eighteenth century onward (in English, Nathaniel Lardner is a good marker), Western writers argued back to Luke’s plain sequence: the sinner’s episode ends; afterward Luke introduces “Mary called Magdalene” among the travelling women. Twentieth-century calendars in both Anglican and Catholic worlds restored her as Easter witness; in 2016 the Roman calendar raised 22 July to a Feast.

Two maps of her later life

The Western constellation (Vézelay and Provence)

Vézelay in Burgundy and, later, the Provençal cluster (Sainte-Baume, Saint-Maximin, Les Saintes-Maries-de-la-Mer) wove a dazzling medieval atlas. Martha tames a dragon at Tarascon; Lazarus becomes a bishop at Marseille; the “Two Marys” and Sarah land in the Camargue. These traditions are late and consolidate in the thirteenth century - the high era of relic competitions, shrine foundations, and pilgrimage economies. They are moving; they are not early.

The Greek-Roman line (Ephesus to Constantinople)

Late, antique and early–medieval writers in the Greek and Latin East place Mary at Ephesus after the Ascension, often in company with St John. In that line:

- Gregory of Tours (6th c.) says her tomb was shown at Ephesus.

- Modestus of Jerusalem (7th c.) affirms the same.

- Willibald (8th c. pilgrim) reports seeing the site.

- Byzantine notices (e.g., Simeon Logothetes) say Leo VI (“the Wise,” late 9th/early 10th c.) translated her relics from Ephesus to Constantinople, often specified as the Church/Monastery of St Lazarus.

From there, later pieces of the story make sense: a left hand at Simonopetra on Athos; a foot reliquary in Rome; passing mentions in pilgrim lists. Debate each fragment if you wish; the route - Ephesus to the capital - fits Byzantine practice and the texts.

Ephesus in the world Mary knew

Roman Ephesus was the Aegean metropolis. You can still walk the marble Sacred Way, trace the Magnesian Gate, and stand on the stage of the Great Theatre where Acts 19 roared, “Great is Diana of the Ephesians!” The city’s Odeum and Bouleuterion sit near the slope; a vast Gymnasium once occupied acres (Justinian would later move its columns to Hagia Sophia). Across the marsh, British Museum excavator J. T. Wood finally located the altar and platform of the Temple of Diana (Artemision), one of antiquity’s wonders: a platform roughly 425 by 220 feet, approached by steps, crowned by a forest of sculpted columns built, Pliny says, upon layers of charcoal and fleece to cushion earthquakes. Herostratus burned an earlier temple the night Alexander the Great was born; the later temple outshone it.

This city is more than backdrop. It held a church founded by Paul, taught by Apollos, nurtured by Aquila and Priscilla, shepherded by Timothy, and ultimately associated with John. It was to Ephesus that the first of the Seven Churches in Revelation is addressed, and it was at Ephesus that the Council of 431 affirmed Mary the Mother of Jesus as Theotokos against Nestorius.

A word on Nestorius (and why it matters here)

Nestorius tried to protect Christ’s divinity by distinguishing the human Jesus from the divine Word so sharply that the unity of Christ’s person was threatened. The council held at Ephesus insisted that the one born of Mary is one and the same person, truly God and truly man. Therefore Mary is rightly Theotokos - “God-bearer” - not because she is the source of the divinity, but because the one she bore is God in person. Ephesus thus became a theological capital. People do not hold ecumenical councils in out-of-the-way places; they meet where roads, ships, and memories converge. The same city that defined Theotokos could easily guard the memory of the Myrrhbearer’s tomb.

The Seven Sleepers: the legend under the hill

Up the hill behind the theatre, a limestone cavern opens under a ridge Greeks have long called the Panaghia Kapouli - the “Virgin’s Doorway.” Late–antique Christians told how, during the persecutions of Decius (249–251), a band of noble Ephesian youths hid in a cave, fell asleep by God’s mercy, and were walled in. Centuries later, when the empire was Christian and controversies about the resurrection raged, a landowner opened the mouth of the cave. The youths awoke hungry, sent one - still carrying old Decius-era coins - down to buy bread, and discovered, to the amazement of the bishop and city officials, that they had slept not hours but generations. They testified to the truth of the resurrection, lay down again, and “fell asleep in the Lord.” The cave became a shrine; a small church grew on the terrace; a spring trickled nearby. Syriac poets told it; Gregory of Tours told it; Aelred told it; Jacob of Voragine told it; the Quran adapted it. The Seven Sleepers became the East’s favorite resurrection parable.

Several local traditions place Mary Magdalene’s burial “at the mouth of the cave.” Whether the exact stone shown today deserves credence is secondary; what matters is the pilgrimage complex: cave, chapel, spring, and sight-line to Ayasuluk and the Basilica of St John. This is the kind of place late antiquity loved and tended, and Mary’s memory sits naturally in it.

Who was with Mary?

In the eastern line she is linked to St John and the circle around him. The simplest telling says she accompanied John to Ephesus, where the Mother of Jesus also lived under his care; there Mary Magdalene died and was buried; and under Leo VI her relics were moved to Constantinople. Variants add preaching in Rome (with the famous red egg to Tiberius) or other travels, but the centre of gravity remains Asia Minor.

The Western legends gather her with Lazarus and Martha in Provence, and with Mary Salome, Mary Jacoby, and Sarah in the Camargue. Those traditions tell us how the medieval West imagined apostolic women should have lived - evangelising, suffering, praying, dying among friends - but they sit at a considerable chronological distance from the first generation.

The House and the archaeology

A separate but related thread concerns the House of the Virgin Mary on bulbul dagi (Nightingale Mountain), above Selçuk. In the late nineteenth century, Catholic missionaries - intrigued by the topographical detail in the visions of Anne Catherine Emmerich - searched the hillside and found the ruins of a small dwelling whose location, approach, and views fit the description surprisingly closely: roughly three and a half leagues from the city, reached by narrow paths, with the sea visible in one quarter. A report of 1 December 1892 acknowledged the match; a modest chapel now marks the site. The recognition is late; the idea that John brought the Mother of Jesus to Ephesus is very old. Whether or not you accept every element of Emmerich’s visions, the geography - house on bulbul dagi, cave of the Seven Sleepers opposite, basilica of St John within view - makes a coherent sacred landscape in which Mary Magdalene belongs.

Archaeology in the plain below is less hagiographical and more granite. J. T. Wood’s trenching fixed the temple and harbour lines; the Great Theatre still speaks with its stone; the Sacred Way still leads your feet. The city that roared at Paul is the same city that gathered bishops; it is the same city where pilgrims climbed to a cave and sipped from a spring.

France revisited - but with chronology in hand

None of this belittles Vézelay, Saint-Maximin, or the Sainte-Baume. Their beauty and the love poured out there tell a truth about the medieval heart. But if we are asking about Mary Magdalene’s tomb, two rules help:

- Temporal priority. The Ephesus tradition is older by centuries; its Constantinopolitan translation fits Byzantine patterns and appears in early sources.

- Parsimony (Ockham). The simplest adequate route - Ephesus to Constantinople, with later dispersals - explains the data without multiplying late “discoveries.”

By contrast, the French claims arrive when Europe was rich in shrine-making and hungry for relics. That context does not cancel devotion; it simply frames it.

Why this matters for Mary herself

Put the pieces together and a consistent profile emerges.

- The number seven in her healing is not a moral insult but a proclamation of total restoration.

- Her name marks her origin - Magdala, the fishing “tower,” not “plaited hair” or “fallen woman.”

- The confusion with other Marys is a late Latin sermon’s legacy; the Greek East never made it.

- The oldest geography keeps her at the heart of the early church: in Ephesus, where Paul taught, John wrote, Timothy served, and bishops met; not exiled to an obscure corner of Gaul, unknown to the communities that guarded the Gospels.

If you walk the Ephesian bowl today, you can see why the memory anchored there. You leave the marble cardo where the merchants once shouted; you climb a goat track under olive shade; you reach the Panaghia Kapouli - the “Virgin’s Doorway” - and the cave mouth cools your face. Below, the rectangle of a ruined chapel; further down, the spring that revived travellers; across the plain, the basilica of St John on Ayasuluk; beyond it, the silting marsh that swallowed the harbour. It is a scene heavy with late–antique meaning: resurrection, council, gospel, pilgrimage. Local guides still point to a stone as the Magdalene’s grave. Stone or no stone, the place makes sense of the woman.

And that is the heart of the matter. Mary Magdalene is not important because she was notorious; she is important because she loved much, because she stood when others fled, because she carried Easter to those who would preach it to the world. The oldest road to her ending leads not to a remote cave of penitence far from the apostolic centres, but to a hill in the very nexus of those centres - Ephesus - and from there, like so many saints of the East, to Constantinople. That is the map that honours both the texts and the earliest memory of the church that knew her.

Feast: 22 July.

Titles: Myrrhbearer. Equal to the Apostles. First witness of the Resurrection.

Probable route of memory: Ephesus to Constantinople to later dispersals.

If we follow that line, Mary Magdalene returns to where she has always belonged: not a cautionary footnote, but a tower in the landscape of the first generation - a woman whose healing was complete, whose name marked a real place, and whose tomb, if we are careful with our sources, belongs among the caves and springs of Ephesus, in the very heart of the early church.

In the West, the penitent Magdalene retreated in exile into a cave in France. In the East, she remained in the city of councils, beside the house of the Theotokos and the ruins of the goddess. That difference is not just legend but theology in stone. The Provencal hermit represents the feminine subdued; the Ephesian disciple represents the feminine integrated - the witness still speaking among apostles, not silenced by them. Ephesus, once the home of Artemis, became the cradle of Marys. In its hills and its council halls the sacred feminine was not erased but redefined - from goddess to Theotokos, from temple to tomb.

Location

Related Articles

12 October 2025

Queen of Heaven: From the Catacombs to the Reformation4 October 2025

The Ancient Blood: A History of the Vampire27 September 2025

Epona: The Horse Goddess in Britain and Beyond26 September 2025

Witchcraft is Priestcraft: Jane Wenham and the End of England’s Witches20 September 2025

The Origins of Easter: From Ishtar and Passover to Eggs and the Bunny12 September 2025

Saint Cuthbert: Life, Death & Legacy of Lindisfarne’s Saint7 September 2025

The Search for the Ark of the Covenant: From Egypt to Ethiopia5 September 2025

The Search for Camelot: Legend, Theories, and Evidence1 September 2025

The Hell Hound Legends of Britain25 August 2025

The Lore of the Unicorn - A Definitive Guide23 August 2025

Saint Edmund: King, Martyr, and the Making of a Cult14 August 2025

The Great Serpent of Sea and Lake11 August 2025

The Dog Days of Summer - meanings and origins24 June 2025

The Evolution of Guardian Angels19 June 2025

Dumnonia The Sea Kingdom of the West17 June 2025

The Roman Calendar, Timekeeping in Ancient Rome14 June 2025

Are There Only Male Angels?