Written by David Caldwell ·

The Origins of Easter: From Ishtar and Passover to Eggs and the Bunny

Discover the history of Easter, from Ishtar and Passover to hot cross buns, eggs, and the Easter Bunny - a festival reborn through pagan, Jewish, and Christian traditions.

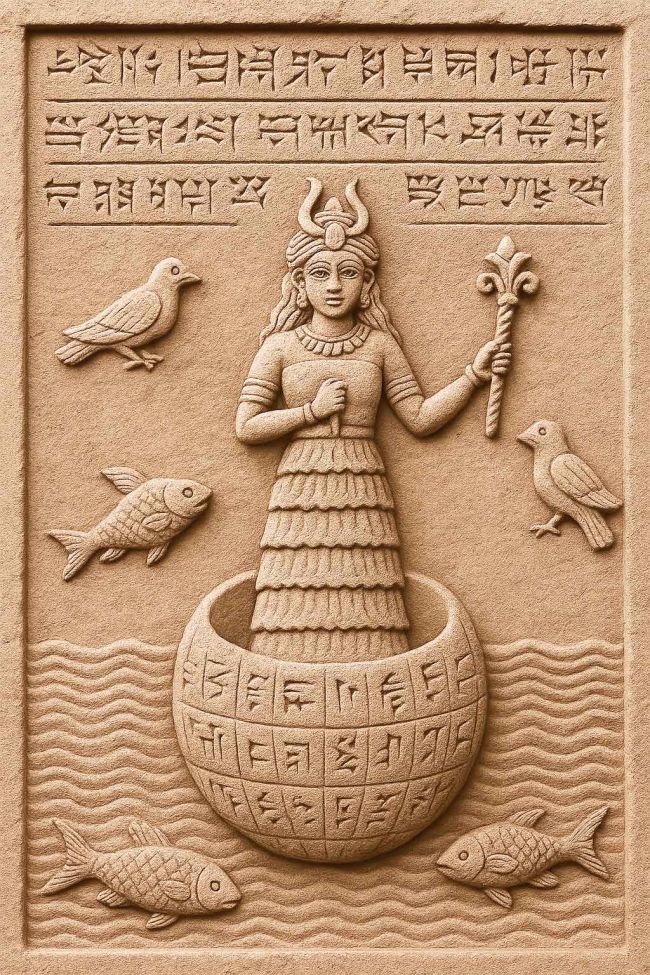

Part 1: The Fertile East - Ishtar, Astarte, and the Queen of Heaven

Before Christianity, and even before Judaism, peoples of the ancient Near East celebrated spring with rites of fertility, renewal, and cosmic order.

Ishtar and Astarte

Ishtar (Babylonian) or Astarte (Phoenician/Syrian) was a goddess of love, war, and fertility, often called the Queen of Heaven. She was associated with both fertility and rebirth, and her worship was widespread from Mesopotamia to the Levant.

The Hebrew prophets condemned her cult in strong terms. Jeremiah records:

“The children gather wood, the fathers kindle the fire, and the women knead dough, to make cakes to the Queen of Heaven, and to pour out drink offerings unto other gods, that they may provoke me to anger.” (Jeremiah 7:18)

Here we see two key elements that echo in later Easter: cakes baked as offerings and ritual feasting tied to a spring goddess.

Victorian antiquarians did not miss the connection. A 1905 commentary, reflecting on Easter buns, insisted:

“In early days this bun was consecrated bread, offered with other treasures to Baal. Sacrifices of sheep and oxen and other animals and fruits of the earth were alike designated. But the custom has not been forgotten, and once again we find the offering of what was considered consecrated cakes.”

The hot cross bun on the Good Friday table was, in their view, the heir of Jeremiah’s “cakes to the Queen of Heaven.”

Why the “Ishtar = Easter” claim is simplistic:

While Easter does not directly descend from Ishtar, there are genuine Near Eastern echoes — in Jeremiah’s condemnation of cakes for the Queen of Heaven, in fertility rites, eggs, and seasonal feasts. The Sumerian-Babylonian-Assyrian empires were ancient superpowers whose gods and goddesses shaped cultures from Egypt and Palestine to Athens and Rome. Ishtar’s essence lived on as Athena and Aphrodite, and the “Queen of Heaven” ultimately resurfaced in Marian devotion. Ishtar’s name faded, but her star and her symbolism did not.

The Cosmic Egg

The egg was equally central in ancient cosmogonies. In Babylonian myth, the egg that fell into the Euphrates and hatched Astarte symbolised life breaking into the cosmos. In Orphic Greek tradition, the universe itself hatched from a cosmic egg. In Egypt, decorated eggs were buried in tombs as emblems of rebirth.

The Victorians again drew the line from antiquity to Easter:

“These Easter eggs seem to have travelled from the banks of the Nile to those of the Euphrates, and thence to the banks of the Tiber, the Thames, and the Taff.” (1890s clipping)

Thus both the bun and the egg - central to modern Easter - have pedigrees stretching back into the oldest fertility cults of the Middle East.

Part 2: Passover and the Jewish Roots of Easter

If Babylon gave Easter its cakes and eggs, Judaism gave it its calendar and its meal. Easter is inseparable from the Jewish Passover - both in the Gospels’ narrative and in the way the Church fixed its date.

The Last Supper and the Paschal Lamb

Passover (Pesach) commemorates the Exodus from Egypt, when the Israelites sacrificed a lamb, marked their doorposts with its blood, and fled Pharaoh’s oppression. It is celebrated on the 15th day of Nisan, the first month of the Jewish year, beginning on the night of the full moon after the spring equinox.

The feast included:

Unleavened bread (matzah), recalling the haste of departure.

Wine, taken in ritual cups.

The lamb, sacrificed in the Temple.

The Gospels tie Christ’s Passion directly to Passover. In Matthew, Mark, and Luke, the Last Supper is described as a Passover meal, where Jesus blesses bread and wine as his body and blood. John’s Gospel shifts the emphasis, portraying Christ’s death as coinciding with the very hour the lambs were slain in the Temple. In both accounts, Jesus is cast as the Paschal Lamb - sacrificed to redeem his people.

Thus from its earliest framing, Easter was grafted onto Passover. It was not simply a spring festival but a transformation of Israel’s feast of liberation into the Christian feast of redemption.

A Movable Feast

Because Passover followed the lunar calendar, Easter became a movable feast too. But Christians insisted on one crucial distinction: Passover could fall on any day of the week, while Easter must be on a Sunday - the day of Christ’s resurrection, and symbolically the day of new creation.

In the second century, this sparked fierce debate between the so-called Quartodecimans (who kept Easter on 14 Nisan regardless of the day) and others who insisted it must follow on Sunday. The controversy was only settled at the Council of Nicaea (325 CE), which declared:

Easter should be observed on the first Sunday after the first full moon after the spring equinox.

This extraordinary formula blended:

the solar year (equinox),

the lunar cycle (full moon),

and the Jewish calendar (Passover).

It was a theological compromise that made Easter a truly cosmic feast, anchored in sun, moon, and salvation history.

Cosmic Harmony and the Annunciation

By the 4th century, theologians imposed a further symmetry: the Annunciation - the conception of Christ in Mary’s womb - was fixed on 25 March, the spring equinox in the Roman calendar. From this date flowed a symbolic harmony:

25 March: Conception (Annunciation) / Passion (Good Friday)

25 December: Birth (Christmas, nine months later at the solstice)

Easter Sunday: Resurrection, after the first full moon of spring

Christ’s life, from conception to resurrection, was thus mapped onto the turning points of the heavens. He became the true “Sun of Righteousness” (Sol Iustitiae, Malachi 4:2), conceived and risen at equinox, born at solstice.

As one 19th-century commentator observed:

“The festival of Easter is determined, not by chance, but by the conjunction of the great lights of heaven, the sun and moon, in their ordained courses. It is therefore no wonder if it absorbed and transformed the rites of those who, before Christ, had sought in sun and moon the promise of renewal.”

Here, Jewish calendar, Christian theology, and cosmic symbolism were united - making Easter not just history, but cosmology in liturgical form.

Part 3: Early Christianity and the Adoption of Symbols

Once Easter was fixed in the Christian year, the early Church did not simply abandon the older signs and customs that clustered around spring. Instead, it absorbed and reinterpreted them. The foods, fasts, and symbols of earlier cultures were carried into Christianity but given new meanings.

Lent and the Middle Eastern Fasting Tradition

From the second century, Christians fasted in preparation for Easter, though the length varied by region. By the 4th century, this became the standard 40 days of Lent, echoing:

Christ’s forty days in the wilderness,

Moses’ forty days on Sinai,

Elijah’s forty days on his journey to Horeb.

But this was not uniquely Christian. Fasting before renewal had long been a Near Eastern tradition - among Jews before Passover, among Zoroastrians before Nowruz, and among Egyptian ascetics. Christianity baptised an older discipline, turning it into preparation for resurrection.

Cakes and Crosses

The offering of sacred cakes, condemned by Jeremiah, also found a curious survival. As one 1905 writer noted, the hot cross bun had a pedigree older than the Church itself:

“In early days this bun was consecrated bread, offered with other treasures to Baal. Sacrifices of sheep and oxen and other animals and fruits of the earth were alike designated. … But the custom has not been forgotten, and once again we find the offering of what was considered consecrated cakes.”

What had been pagan cakes marked with solar signs became Christian buns marked with crosses. In medieval England, they were eaten on Good Friday: their cross for the Crucifixion, their spices recalling Christ’s burial. A Victorian observer quipped that Londoners “paid homage to the goddess in Fleet Street” when queuing for their Good Friday buns.

The form endured, but the meaning was rewritten.

Eggs as Tomb and Resurrection

The egg, too, was not discarded but redeemed. In the East, it symbolised the sealed tomb of Christ, broken open on Easter morning to reveal new life. Eggs dyed red for the blood of Christ became traditional gifts.

So central was the egg’s Christian reinterpretation that Pope Paul V composed a special prayer:

“Bless, O Lord, we beseech Thee, this Thy creature of eggs, that it may become a wholesome sustenance to Thy faithful servants, eaten in thankfulness to Thee on account of the Resurrection of Our Lord Jesus Christ.”

Thus the cosmic egg of Babylon, the painted egg of Egypt, the serpent’s egg of Celtic lore, all found themselves carried into the Easter vigil basket, reborn as symbols of Christ’s victory over death.

A Pattern of Christianisation

The early Church did not so much suppress older symbols as reframe them. Cakes became buns for Christ. Eggs became tombs and resurrections. Fires became Paschal lights. Fasts became Lent.

One Victorian antiquarian summed up this process candidly:

“Thus we see that the very name of Easter [is] identified with one of the heathen goddesses, and that its observance is a mere adaptation of pagan customs handed down for the benefit of the Christian Church.”

Part 4: Into Britain - Celts, Saxons, and the Question of Survivals

When Christianity spread into Roman Britain and later flourished in Ireland, Wales, and Anglo-Saxon England, it encountered local calendars and traditions. Victorian folklorists loved to imagine a straight line of continuity from Druids to Easter eggs and hares. But the historical record is far more complicated.

Bede and the Goddess Eostre

The earliest reference to a pagan spring goddess in Britain comes from Bede’s De Temporum Ratione (725 CE):

“Eosturmonath, which now is interpreted ‘Paschal month,’ once was called after a goddess of theirs named Eostre, in whose honour feasts were celebrated in that month. Now they designate that Paschal season by her name, calling the joys of the new rite by the time-honoured name of the old observance.”

This single line is the only historical evidence we have for a goddess named Eostre. She appears in no Irish or Welsh texts, no inscriptions, no archaeology. Some scholars think Bede was simply speculating about a month-name. Yet from this fragile seed grew the whole modern idea that Easter derives from a pagan English goddess.

Notably, Bede says nothing about eggs, hares, or cakes in connection with her.

Where is the evidence for Eostre?

The only ancient reference to a goddess called Eostre comes from a single sentence in Bede’s De Temporum Ratione (725 AD), where he explained that the Anglo-Saxons once named April after a goddess of theirs. No inscription, altar, or dedication to such a deity has ever been found in Britain or on the Continent, despite the Romans recording and adopting scores of Celtic and Germanic gods and goddesses such as Brigantia, Coventina, and Sagarmangabis. Even foreign cults like Isis and Cybele left a deep imprint across the empire, yet Eostre is absent from archaeology, classical literature, and Roman syncretism.

This silence has led many scholars to question whether Bede was reporting genuine folk memory, or whether he was speculating on the month-name and filtering it through the biblical trope of the “Queen of Heaven” condemned by Jeremiah. If Eostre ever existed, she left no trace outside Bede’s pen.

Some scholars point to the Matronae Austriahenae inscriptions near Bonn as supporting evidence, but these were localised ‘mother goddess’ cults, and the name may simply reflect geography rather than a universal dawn deity. Without Bede, these stones would likely never have been connected to Easter.

Celtic Churches and the Synod of Whitby

For the Celtic churches, the great Easter controversy was not about folk customs but about when to celebrate the feast. Irish and Welsh Christians followed one computus, while Rome followed another.

At the Synod of Whitby (664 CE), the Northumbrian king Oswiu decided in favour of the Roman calculation. This was a political as well as a religious act, binding the English church more closely to continental Christendom.

The dispute shows that Easter mattered deeply - but as a calendrical and theological festival, not as a folk rite.

Hares in Celtic and Classical Sources

Still, hares did hold sacred importance in Celtic and pre-Christian Britain. Julius Caesar noted in his Gallic Wars that the Britons did not eat hares, suggesting they were taboo or holy. Archaeologists have uncovered hare burials at Iron Age sites such as Maiden Castle, apparently placed with ritual intent.

In Irish and Welsh folklore, hares appear as witches in disguise or lunar animals. The famous “three hares” motif, carved into medieval church bosses in Devon and Wales, shows three hares chasing each other in a circle, their ears forming a triquetra. This powerful symbol, possibly imported from the Silk Road, became embedded in both pagan and Christian iconography.

Yet no Celtic source ties hares specifically to Easter. Their sacredness was real, but their connection to the resurrection feast is Victorian projection.

Serpent’s Eggs and Druid Lore

Pliny the Elder records a striking Celtic belief in the ovum anguinum, the “serpent’s egg”:

“The Druids say that it is formed by the slime of serpents, and thrown into the air by the hissing of their entangled bodies. The egg must be caught in a cloak, before it touches the earth.” (Natural History, 29.3)

These eggs were said to give magical powers to their bearers. This shows that eggs held symbolic importance in Celtic imagination - not for Easter, but for magic, life, and power.

Victorian Folklore and the Idea of Continuity

Victorian folklorists seized on these scraps - Bede’s Eostre, Caesar’s hares, Pliny’s serpent’s egg - and declared them the “pagan roots” of Easter. One 19th-century newspaper confidently claimed:

“The cakes of Jeremiah, the serpent’s egg of the Druids, and the hares of Caesar’s Britain are all but fragments of the same great spring festival, surviving beneath new names in the Christian Easter.”

Modern scholarship is more cautious. There is no clear continuity from Celtic ritual to Easter. Instead, Easter was introduced as a Christian feast into Britain, and only later did it absorb local symbols such as the hare into its orbit.

Part 5: Medieval Europe - Christianisation of Symbols

By the Middle Ages, Easter had taken on its mature form as the central feast of Christendom. The liturgy was rich - the Easter Vigil with its fire, Exsultet hymn, and blessing of water and light. Yet alongside this official worship flourished a host of folk customs, many of which echoed older traditions while being firmly embedded in Christian meaning.

Hot Cross Buns and Good Friday Cakes

The ancient cakes to the Queen of Heaven, denounced by Jeremiah, had by now been remade as Good Friday buns. In medieval England these were solemnly baked, marked with a cross, and eaten as both food and sacrament. Their symbolism was layered:

The cross for the Crucifixion.

The spices recalling Christ’s embalming.

The round shape for eternity.

A Victorian antiquarian drew the line explicitly:

“In early days this bun was consecrated bread, offered with other treasures to Baal. Sacrifices of sheep and oxen and other animals and fruits of the earth were alike designated. But the custom has not been forgotten, and once again we find the offering of what was considered consecrated cakes.” (1905)

Thus the Good Friday bun became a perfect example of pagan form filled with Christian content.

Easter Fires and the Paschal Light

Another widespread custom was the lighting of Easter fires. In many parts of Europe, great bonfires were lit on Holy Saturday or Easter Sunday morning. The Church sanctioned these as the lighting of the Paschal candle - Christ as the light of the world.

But the older echoes were obvious. As one 19th-century account reminded its readers:

“The lighting of bonfires and leaping through the flames are as old as Baal worship. These flames, once sacred to the sun, are now hallowed to Christ, the true light.”

The continuity of fire as a symbol of renewal was unmistakable, though reinterpreted by the Church.

Dyed and Blessed Eggs

By the 12th century, eggs had become a standard part of Easter in both East and West. They were:

Dyed red to symbolise Christ’s blood.

Painted or gilded as festive gifts.

Blessed by priests in baskets at the vigil.

Egg rolling, still popular today, was already known in parts of Europe - the rolling egg symbolising the stone rolled away from Christ’s tomb.

Pope Paul V’s prayer over Easter eggs made their Christian symbolism explicit:

“Bless, O Lord, we beseech Thee, this Thy creature of eggs … eaten in thankfulness to Thee on account of the Resurrection of Our Lord Jesus Christ.”

The Weaving of Liturgy and Folk Practice

In medieval Europe, the official Church and popular custom were not at odds but woven together. The same egg could be a child’s toy and a sacramental object; the same bun could be a treat and a symbol of Calvary. Fires could be both village revelry and Paschal rite.

Victorian commentators, ever eager to detect pagan survivals, often overstated the case. Yet they were not wrong to sense that Easter’s medieval forms were layered with echoes of older rituals, re-baptised by the Church.

Part 6: Germanic and Victorian Layers

By the early modern period, Easter had become firmly established across Europe. Yet two major additions were still to come: the German Easter Hare and the Victorian antiquarian imagination that sought pagan roots in every symbol.

The German Osterhase

The first clear reference to an Easter Hare (Osterhase) comes from 17th-century Germany. The hare was imagined as a magical creature that laid coloured eggs for children to find. This curious blend of sacred animal and festive reward spread rapidly across German-speaking lands.

When German immigrants settled in America, they carried the custom with them. By the 18th century, Pennsylvania Dutch communities were celebrating Easter with egg-laying hares. Britain only adopted the tradition later, in the Victorian period, when German Easter customs were fashionable imports.

The hare’s introduction into Easter built upon older European folklore. Hares had long been linked with the moon, fertility, and taboo. But the Easter Bunny, as we know it, was a German innovation, absorbed into British life only in the 19th century.

Sugared and Chocolate Eggs

Eggs had been painted, dyed, and gilded since antiquity. But it was in the 18th and 19th centuries that confectioners began to create sugar-moulded eggs and eventually chocolate eggs. By the mid-Victorian era, chocolate eggs were mass-produced and widely exchanged.

Not everyone was impressed. One commentator complained of the scale of the trade:

“The only fault I find with eggs is for making so much of these adorable subjects in Easter festivities in the various forms of the artful dodgers, who roll about countless thousands of sugared Christian eggs every year round, and send out of the country the odd million a year or more to pay for eggs from the continent which might have been produced in our own island home.” (1890s newspaper clipping)

Here, the ancient cosmic egg had been fully commercialised.

Victorian Antiquarianism

The 19th century was the golden age of folklore studies. Victorian writers relished connecting Christian customs to pagan antiquity. Easter, with its eggs, buns, and fires, became a favourite subject.

The Ludlow Advertiser (1891) confidently traced Easter eggs back to Babylon:

“The Babylonians had a mystic egg which they said had fallen from heaven into the river Euphrates, and was rolled by the fishes to the bank, where the doves settled upon it, and hatched from it. The woman they worshipped as the Queen of Heaven, called Astarte. Thus the dove and the egg became her symbols, and golden eggs as well as painted were used in their sacred festivals, and were called Astarte’s eggs. The people of Nineveh pronounced Astarte mostly as we pronounce Easter.”

A 1905 essay drew the same line between Jeremiah’s cakes and the hot cross bun:

“In early days this bun was consecrated bread, offered with other treasures to Baal. Sacrifices of sheep and oxen and other animals and fruits of the earth were alike designated. … But the custom has not been forgotten, and once again we find the offering of what was considered consecrated cakes.”

For the Victorians, the case was clear: Easter’s eggs and buns were not Christian inventions but Christianised survivals of Babylonian and Phoenician rites. Modern scholars are more cautious, but the Victorian instinct captured something real - Easter is a feast of layered symbols, reborn across cultures.

Related Articles

4 October 2025

The Ancient Blood: A History of the Vampire27 September 2025

Epona: The Horse Goddess in Britain and Beyond26 September 2025

Witchcraft is Priestcraft: Jane Wenham and the End of England’s Witches12 September 2025

Saint Cuthbert: Life, Death & Legacy of Lindisfarne’s Saint7 September 2025

The Search for the Ark of the Covenant: From Egypt to Ethiopia5 September 2025

The Search for Camelot: Legend, Theories, and Evidence1 September 2025

The Hell Hound Legends of Britain25 August 2025

The Lore of the Unicorn - A Definitive Guide23 August 2025

Saint Edmund: King, Martyr, and the Making of a Cult14 August 2025

The Great Serpent of Sea and Lake11 August 2025

The Dog Days of Summer - meanings and origins24 June 2025

The Evolution of Guardian Angels19 June 2025

Dumnonia The Sea Kingdom of the West17 June 2025

The Roman Calendar, Timekeeping in Ancient Rome14 June 2025

Are There Only Male Angels?