Written by David Caldwell ·

Queen of Heaven: From the Catacombs to the Reformation

The concept of a divine feminine-of a goddess who embodies compassion, fertility, wisdom, or love-is nearly universal in the world’s religions. From Isis nursing Horus to Athena guarding Athens, ancient cultures found a need for the mother, the protector, the merciful intercessor. Yet within Judaism, this principle was absent. Yahweh was wholly masculine, transcendent, and unapproachable. The Hebrew Bible gave little space for the sacred feminine beyond fragments: the figure of Wisdom in Proverbs, and a lamenting motherly voice in Isaiah. The only overt trace of a goddess appears as a warning rather than a revelation. In the Book of Jeremiah, the prophet condemns those who make cakes and burn incense to “the Queen of Heaven” (Jer. 7:18; 44:17-19). The tone is one of outrage: the Israelites, in exile, have begun venerating a mother goddess, likely the Canaanite Asherah or Astarte. Her cult was popular, her offerings domestic, her comfort human. Jeremiah’s God would have none of it.

And yet, centuries later, the same title Queen of Heaven would be lovingly sung in Christian prayers to Mary, the mother of Jesus.

How this transformation occurred-how a condemned idol became an emblem of divine mercy-is one of the most fascinating evolutions in religious history. It reveals not only theological adaptation but a deep human need to see the divine reflected in both genders.

Mary Magdalene and the Forgotten Apostolate

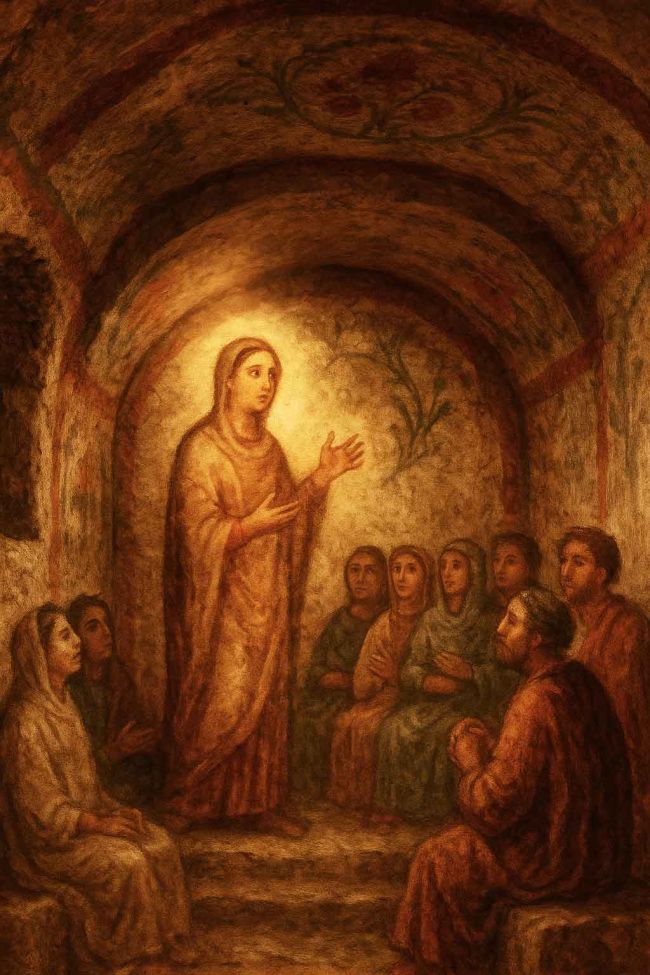

Amid the evolving imagery of the divine feminine, another Mary once stood at the centre of the early Christian story - not the mother, but the witness.

Mary Magdalene was not a marginal figure in the earliest circles of believers. She stood by the cross when others fled. She was the first to see the risen Christ and the first to proclaim his resurrection. In the earliest resurrection narratives, she is the apostle to the apostles, charged with carrying the good news to those who had lost hope.

But as the Church institutionalised, her prominence faded.

In the non-canonical gospels - Mary, Philip, and Pistis Sophia - she is not only a witness but an interpreter, a visionary who grasps the hidden meaning of Christ’s words. The disciples, particularly Peter, question her authority:

“Did the Saviour really speak with a woman and not openly to us?”

Levi defends her, saying Jesus loved her more than any other disciple - a statement that, in symbolic terms, means she was most fully enlightened. In these texts, Mary Magdalene is the embodiment of Sophia, divine Wisdom, the spark of understanding that bridges heaven and earth. Her spiritual authority represents the earliest Christian attempt to reclaim the feminine face of the Spirit.

Some early communities - particularly Gnostic and Syrian Christians - revered her as the true successor to Christ’s teaching. She inspired her own following, one that emphasised inner revelation over

hierarchy, experience over law, and equality of the sexes in the spirit.

In this sense, her movement paralleled and at times rivalled the Pauline one. Paul’s letters, written in the decades after her witness, reflect a shift toward order, hierarchy, and male authority. Where Mary represented illumination and direct communion, Paul represented governance and doctrine.

By the second century, the tension was resolved not by synthesis but by suppression. Mary Magdalene’s gospel was lost, her role reduced to that of penitent sinner - a conflation with Mary of Bethany and the “woman taken in adultery” that served to neutralise her apostolic legacy.

Yet her memory lingered. The Eastern Church still called her Equal to the Apostles, and in art she stood with the red egg of resurrection, the colour of life and spirit. In Western devotion she became the weeping saint of compassion, precursor to Marian tenderness. Where the Magdalene had once proclaimed resurrection, the Virgin would come to embody intercession.

Even in her obscurity, the Church could not entirely erase her radiance. Her story hints that the Christian instinct for a feminine vessel of divine wisdom did not begin with Mary the Mother, but with Mary the Witness.

By later rejecting Marian veneration as idolatry, the reformers may have dismissed a truth that was once self-evident to those who first came into Mary’s orbit - that the divine can shine most brightly through compassion, and sometimes through her.

The Plain Faith of the First Believers

The first Christians were Jews, and they inherited Judaism’s distrust of images. Their early worship was austere. In the catacombs beneath Rome, the earliest tombs of believers-dating from the late first to the early second century-were marked only with simple symbols: the fish, the anchor, the chi-rho. There were no saints, no Madonnas, no halos. These were communities still shaped by persecution, secrecy, and poverty. Their art was coded rather than ornate, and their theology focused on resurrection and hope rather than hierarchy or intercession.

As Christianity spread among the Gentiles, this simplicity began to change. Converts from the Greek and Roman world brought with them not only their language but their sense of imagery, symbolism, and ritual. The Christian message began to take on a visual splendour it had never known in the synagogues of Judea. By the late second and third centuries, the catacombs were becoming small subterranean galleries of faith. Alongside biblical scenes of Jonah or Daniel appeared shepherds, vines, and figures of women in prayer.

One of the earliest of these images, found in the Catacomb of Priscilla, shows a woman holding a child on her lap while a figure-perhaps a prophet or angel-gestures toward them. Scholars have debated whether this is simply a generic mother and child, or the Virgin Mary with the infant Christ. Whatever the intention, later Christians saw in it the prototype of the Madonna. By the fourth century, such images had become frequent enough for visitors to remark on “paintings of the Blessed Virgin with her Divine Son in her arms” adorning the burial chambers of the martyrs.

This shift-from symbol to person, from abstract faith to personal intercession-marked a turning point. Christianity was no longer a small Jewish sect; it was a cosmopolitan religion with adherents from Syria to Spain. And those adherents, especially women, wanted a figure they could speak to.

Mary Among the Goddesses

The Assumption itself echoes imperial ritual: when an emperor was to be deified, witnesses were required to testify that they had seen his soul ascend to heaven. Likewise, the Virgin’s ascent serves as celestial authentication — a divine proclamation made visible. The language feels curiously Roman: a fusion of theology and ceremony where heaven ratifies earth’s chosen vessel.

It is no coincidence that Marian imagery flowered in Rome, the city of Venus, Juno, and Isis. The Roman world was thick with mother goddesses. Isis, imported from Egypt, was perhaps the most beloved. Her statues showed her nursing the infant Horus on her lap, the child’s head cradled against her breast. Processions of her devotees filled the streets with incense, music, and flowers. When Christianity began to spread among the same populace, it did not erase this imagery but repurposed it.

Early Christian preachers did not worship Mary, but they exalted her obedience and purity in contrast to Eve’s disobedience. Yet for the common believer, visual art spoke louder than doctrine. The image of a serene mother holding her divine son was not easily distinguished from Isis and Horus or from statuary of Fortuna and her child Plutus. The psychological continuity was clear: if the old gods were gone, the longing they had satisfied remained.

By the third and fourth centuries, Christian theologians such as Origen and Ephrem the Syrian were already calling Mary the new Eve, the one whose obedience had undone the fall. Devotion grew rapidly after Constantine’s conversion and the end of persecution. As the Church gained wealth and status, so too did its art. The once-plain catacombs gave way to basilicas glittering with mosaics, where Mary stood beside Christ as queenly intercessor.

When the Council of Ephesus met in 431 AD, the debate was not whether Christ was divine-by then that was settled-but whether Mary could rightly be called Theotokos, “God-bearer.” Nestorius, Patriarch of Constantinople, had objected, arguing that Mary bore the human Jesus, not the divine Logos. The council declared otherwise: Mary was indeed the mother of God, for the person she bore was one and indivisible. The title Theotokos affirmed both Christ’s unity and Mary’s exalted role.

This decision was not merely theological. In the streets of Ephesus-once a center of Artemis worship-crowds celebrated the decree with torches and hymns, crying “Theotokos!” as they once had invoked the goddess. The maternal archetype had found a new home.

Mary in the North: From Isis to Brigid

As Christianity moved northward, Marian devotion intertwined with local traditions. In the Celtic world, Brigid-the fiery goddess of poetry, smithcraft, and healing-was transformed into Saint Brigid of Kildare. The saint’s attributes-her perpetual flame, her compassion, her protection of mothers and livestock-echoed the older goddess so closely that the two are impossible to disentangle.

Here again, the archetype of the divine feminine proved irrepressible. The people of Ireland, long accustomed to revering powerful female deities, transferred their loyalty to a Christian virgin who shared their qualities. The process was not deceit but continuity; a merging of spiritual languages. Just as Mary in Rome absorbed aspects of Isis and Juno, so Brigid became a northern manifestation of the same maternal spirit-the compassionate mediatrix between humanity and the divine.

Martha, Mary Magdalene, and the Feminine in the Gospels

Within the Gospels themselves, women occupy a surprisingly central role, though the official theology of early Christianity was dominated by men. Martha and Mary of Bethany represent two archetypes: Martha, the active servant; Mary, the contemplative disciple who “chose the better part.” Mary Magdalene, meanwhile, stood at the cross when the male disciples fled and was the first witness of the Resurrection.

The early Church Fathers were uneasy with this prominence. They spiritualised the women into symbols of virtues rather than individuals of authority. Yet in the folk imagination-and in art-they remained close to the heart of devotion. Mary Magdalene’s tearful repentance and Christ’s forgiveness made her the model of mercy; Martha’s service became the image of humble piety. Together they embodied the balance between contemplation and action, a duality that would later be absorbed into the Marian ideal: the Virgin who pondered in her heart and yet served all.

The Rise of the Queen of Heaven

By the fifth and sixth centuries, Mary had become the emotional heart of Christian piety. Churches were dedicated to her; hymns and prayers invoked her intercession. She was the new Eve, the Mother of God, and increasingly the Queen of Heaven. The imagery was rich: she was the woman clothed with the sun from Revelation 12, the star of the sea guiding sailors, the throne of wisdom, the gate of heaven.

Art followed theology. Mosaics in Rome’s Santa Maria Maggiore (c. 440 AD) show her enthroned beside the infant Christ, flanked by angels-a vision of imperial majesty that owes much to Byzantine court ceremony. The Mother of God was now also the Mother of the Empire.

This transformation both elevated and softened Christianity. Where the Father and Son represented judgment and sacrifice, Mary offered mercy and refuge. The Salve Regina, composed in the eleventh century, called her “our life, our sweetness, and our hope.” In the age of plague and war, she became the mediator between a suffering humanity and a distant God.

From Devotion to Doctrine

Through the Middle Ages, Marian devotion expanded with astonishing vitality. Pilgrimage shrines arose at Chartres, Walsingham, and Loreto; miracle stories multiplied; the rosary became a daily rhythm of life. Theologians such as Bernard of Clairvaux and Thomas Aquinas refined the idea of her perpetual virginity and intercessory power.

By the thirteenth century, Mary was not only the mother of Christ but the embodiment of the Church itself-pure, faithful, and nurturing. She appeared in visions to mystics, wept in statues, and, in the art of the Gothic cathedrals, stood at the center of the celestial hierarchy.

Yet the very success of her cult invited reaction. The Protestant reformers of the sixteenth century saw in Marian devotion the proof of Rome’s corruption. To Martin Luther, Mary remained worthy of honour as the humble handmaid of God, but the later accretions-her titles as mediatrix and queen-were condemned as idolatry. John Calvin was harsher still, calling Marian intercession a blasphemous usurpation of Christ’s unique role.

Weaponised Womanhood: The Reformation Fracture

After the Reformation, Mary became more than a theological figure-she became a symbol of the divide itself. In Catholic lands she was painted on battle standards, invoked by Jesuits and crusaders, crowned in processions as the banner of orthodoxy. In Protestant lands she was denounced from pulpits as the “Roman goddess of mercy,” a relic of pagan superstition.

Nineteenth-century polemicists revived the old charge that Catholics had simply replaced Isis and Astarte with Mary. Letters in English newspapers spoke of the “Roman goddess with her child,” found in Chinese temples or Roman ruins, as evidence of a universal idolatry. The Dublin Evening Mail thundered against the “dual divinity” of Pope and Virgin; the Warder and Dublin Weekly Mail mocked the “Roman goddess of mercy and lost sheep.”

Meanwhile, Catholic scholars and travellers defended their faith by pointing to archaeology itself: the frescoes of the catacombs, the ancient inscriptions calling Mary Advocata Christianorum. These, they argued, proved that devotion to her was as old as Christianity, not a pagan intrusion. Articles in the Derry Journal and the Mayo Examiner reported discoveries of Marian frescoes from the first centuries, “seen and venerated, if not by the Apostles Peter and Paul themselves, at least by their immediate disciples.”

Thus the argument turned archaeological: each side digging into history to vindicate its vision of purity.

The North Remembers: Brigid and Continuity

While theologians debated, the popular devotion of the people followed older instincts. In Ireland and Scotland, where the figure of Saint Brigid had long merged with the goddess of the same name, Marian piety took on a distinct northern hue. Holy wells dedicated to Brigid or Mary became centers of healing; candle festivals on Candlemas and Imbolc blended Christian and pre-Christian customs. The image of the Virgin with the Child found its echo in folk art and song-often less a theological statement than a human one, celebrating motherhood itself.

This continuity between goddess, saint, and mother is not proof of paganism, as earlier polemicists claimed, but evidence of spiritual adaptation. When older forms of reverence met new faiths, they sought expression in the language of compassion rather than conquest. The figure of the maternal divine persisted because it answered a need untouched by doctrinal dispute: the need for tenderness within the sacred.

From the Enlightenment to the Present

By the eighteenth century, Enlightenment rationalism dismissed all such devotions as superstition. But Romanticism soon revived them in art and poetry. The Virgin became an emblem of purity and beauty in works by Blake, Keats, and Dante Gabriel Rossetti. In the nineteenth century, new Marian apparitions-Lourdes (1858), La Salette (1846), Fatima (1917)-rekindled mass devotion, while the 1854 proclamation of the Immaculate Conception and the 1950 dogma of the Assumption confirmed her doctrinal centrality.

In Protestant nations, she remained controversial, yet her image slipped quietly into culture-into carols, paintings, and even secular iconography. The “Madonna and Child” became not only a religious subject but a universal symbol of maternal love. Art historians of the twentieth century, openly acknowledged the continuity between Isis and Mary, Horus and Christ. What had once been a polemical insult became an accepted observation: the Madonna is heir to the mother goddess of antiquity.

The Enduring Queen

From Jeremiah’s condemnation of the “Queen of Heaven” to modern Marian devotion, the trajectory is paradoxical. The prophets of Israel rejected the goddess; Christianity re-embraced her in transformed guise. The early Jewish Christians buried in the plain catacombs would scarcely recognise the golden icons of the Renaissance, yet the instinct that created them-the longing for intercession, compassion, and divine motherhood-is as old as faith itself.

Mary’s evolution from humble handmaid to crowned Queen of Heaven mirrors the evolution of Christianity from persecuted sect to imperial faith, from desert simplicity to cathedral splendour. She is, in a sense, the Church personified: simultaneously human and exalted, sinner’s advocate and seat of wisdom, daughter of Israel and mother of God.

Even after the fractures of the Reformation, she remained the most recognisable face of Christianity. Protestants might reject her cult, but they could not erase her image. Her presence in art, music, and literature endured because she speaks to something deeper than doctrine-the reconciliation of the human and the divine, the need for tenderness beside authority, mercy beside judgment.

In the north, she walks still with Brigid by the wells; in the south, she glimmers in candlelight over altars. Whether worshipped, venerated, or simply admired, the Queen of Heaven continues to embody what Jeremiah’s people longed for and his God forbade: the eternal feminine face of the divine.

Related Articles

4 October 2025

The Ancient Blood: A History of the Vampire27 September 2025

Epona: The Horse Goddess in Britain and Beyond26 September 2025

Witchcraft is Priestcraft: Jane Wenham and the End of England’s Witches20 September 2025

The Origins of Easter: From Ishtar and Passover to Eggs and the Bunny12 September 2025

Saint Cuthbert: Life, Death & Legacy of Lindisfarne’s Saint7 September 2025

The Search for the Ark of the Covenant: From Egypt to Ethiopia5 September 2025

The Search for Camelot: Legend, Theories, and Evidence1 September 2025

The Hell Hound Legends of Britain25 August 2025

The Lore of the Unicorn - A Definitive Guide23 August 2025

Saint Edmund: King, Martyr, and the Making of a Cult14 August 2025

The Great Serpent of Sea and Lake11 August 2025

The Dog Days of Summer - meanings and origins24 June 2025

The Evolution of Guardian Angels19 June 2025

Dumnonia The Sea Kingdom of the West17 June 2025

The Roman Calendar, Timekeeping in Ancient Rome14 June 2025

Are There Only Male Angels?