Convert a date to a Roman Date

October (October 2025)

| Sun | Mon | Tue | Wed | Thu | Fri | Sat |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

K 1 | a.d. 5 2 | a.d. 4 3 | a.d. 3 4 | |||

a.d. 2 5 | a.d. 1 6 | N 7 | a.d. 7 8 | a.d. 6 9 | a.d. 5 10 | a.d. 4 11 |

a.d. 3 12 | a.d. 2 13 | a.d. 1 14 | I 15 | a.d. 16 16 | a.d. 15 17 | a.d. 14 18 |

a.d. 13 19 | a.d. 12 20 | a.d. 11 21 | a.d. 10 22 | a.d. 9 23 | a.d. 8 24 | a.d. 7 25 |

a.d. 6 26 | a.d. 5 27 | a.d. 4 28 | a.d. 3 29 | a.d. 2 30 | a.d. 1 31 |

a.d. = ante diem (the day before).

Written by David Caldwell ·

The Roman Calendar, Timekeeping in Ancient Rome

Roman Time: From Caesar's Reforms to the Madness of the Medieval Calendar

In the wake of civil war, with the Roman Republic teetering, Julius Caesar emerged as the dominant force following his dramatic victory over Pompey the Great at the Battle of Pharsalus in 48 BC. Pompey, once Rome's most celebrated general, fled across the Mediterranean to Egypt, seeking refuge with the ruling Ptolemaic dynasty. But Egypt, ever a land of intrigue, had its own politics to play. Caesar arrived in Alexandria to a gruesome diplomatic overture: the severed head of Pompey presented in a jar by Ptolemy XIII's faction, hoping to win Roman favour.

Caesar, however, recoiled at the brutal display. Whether from genuine disgust or political calculation, he instead threw his support behind the enigmatic and politically astute Cleopatra VII. Cleopatra, said to possess both charm and brilliance, forged an alliance, and perhaps more, with Caesar. Their union allegedly produced a child, Caesarion, and during this time, Caesar used his stay in Egypt not merely for romance, but for reform.

The Library of Alexandria, a beacon of ancient knowledge, offered Caesar access to the most advanced astronomical thought of the age. With Roman civil timekeeping in disarray, leap years misapplied, festival dates adrift, and months no longer in sync with the seasons, Caesar sought to reset Rome’s relationship with time itself.

The result was the Julian Calendar: a solar calendar with 365 days, and a leap year every four. It replaced the older lunar-based Roman calendar, which had required constant adjustment and manipulation by pontifices, often for political ends. The Julian reform established a structure that would endure for over 1,600 years, only finally corrected by Pope Gregory XIII in 1582.

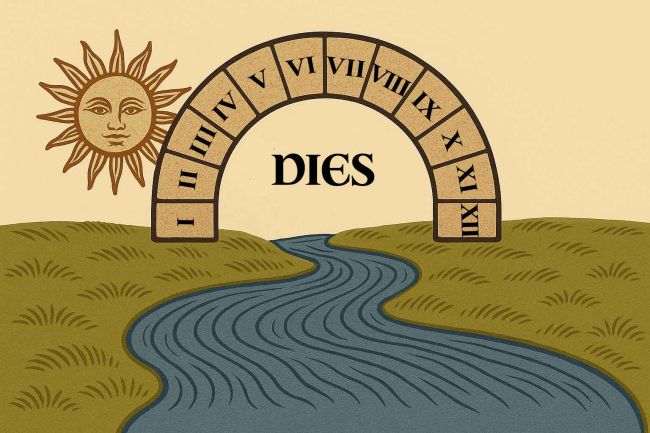

Timekeeping in Ancient Rome

Roman days were divided into 12 hours of daylight and 4 night watches (or "vigiliae"). The length of each hour varied with the seasons, shorter in winter, longer in summer, since the hours simply divided the daylight, not fixed periods as we use today.

The civil calendar, inherited from Etruscan and earlier Roman systems, was structured around three fixed points:

- Kalends (the 1st of the month), from kalare, "to call" or proclaim, when debt and interest were due.

- Nones, either the 5th or 7th day depending on the month.

- Ides, either the 13th or 15th, often marking the full moon.

Dates were reckoned backwards from these points, inclusive of the target day. For example, March 3rd would be "five days before the Nones of March." This anticipatory reckoning mirrored Roman military precision and festival calculation. "Pridie Kalendas" (the day before the Kalends) was as specific as the calendar got.

Months were classified as either full (31 days) or hollow (29 days). The reforms under Caesar made the months more regular, but kept the poetic names and structure.

The Nundinal Cycle: An Eight-Day Week

Running alongside the familiar solar seven-day week was the Nundinal cycle, an eight-day market week (A through H), where rural citizens would come into town to trade. Schools, courts, and religious observances were often tied to these market days. Each day of this cycle was marked by a letter, carved into stone calendars and sundials. It was a practical, agrarian rhythm that endured until it was gradually replaced by the planetary week introduced in imperial times.

Planetary Rulers of the Roman Week

To this day, it is still possible to calculate the Roman Nundinal letter for any given date using known fixed reference points. One such reference is the Nundinal letter for January 1, 1 AD (Julian calendar), which is recorded as A. By counting forward using an 8-day cycle, we can determine the Nundinal letter for any modern date.

By the Imperial period, the Romans had adopted the planetary seven-day week, a system inherited from Babylonian astrology and aligned with Hellenistic traditions. Each day was ruled by a celestial body and its corresponding deity:

Planetary Rulers of the Roman Week

- Dies Solis – Ruled by Sol (the Sun) – Modern: Sunday – Named after the Sun

- Dies Lunae – Ruled by Luna (the Moon) – Modern: Monday – Named after the Moon

- Dies Martis – Ruled by Mars – Modern: Tuesday – Named after Tiw (Norse god of war)

- Dies Mercurii – Ruled by Mercury – Modern: Wednesday – Named after Woden (Odin, Norse Mercury)

- Dies Iovis – Ruled by Jupiter (Jove) – Modern: Thursday – Named after Thor (Norse Jupiter)

- Dies Veneris – Ruled by Venus – Modern: Friday – Named after Freya (Norse Venus)

- Dies Saturni – Ruled by Saturn – Modern: Saturday – Named after Saturn

This planetary week ran in parallel with the Nundinal cycle for a time, before gradually replacing it as the dominant structure in late antiquity and the Christian era.

Running alongside the familiar solar seven-day week was the Nundinal cycle, an eight-day market week (A through H), where rural citizens would come into town to trade. Schools, courts, and religious observances were often tied to these market days. Each day of this cycle was marked by a letter, carved into stone calendars and sundials. It was a practical, agrarian rhythm that endured until it was gradually replaced by the planetary week introduced in imperial times.

Roman Timepieces: Shadows and Water

Despite their eventual sophistication, the Romans were late adopters of sundials. The first known sundial in Rome was brought from Catania in Sicily around 263 BC, and for decades it told the wrong time due to the difference in latitude. Over time, however, Roman sundials evolved into intricate instruments.

Portable sundials shaped like rams, lions, or other animals became fashionable among elites. These pocket dials used a gnomon and latitude adjustments to read solar time. Some, like the ram-shaped dial, included inscribed zodiac signs and month names, allowing users to track both time and season.

More sophisticated fixed sundials were designed with conical or hemicyclium shapes, calibrated for specific latitudes, with engraved lines for hours, seasons, and solstices. One such example found in France included inscriptions in Greek and Latin, reflecting the fusion of Roman and Hellenistic knowledge.

Romans also adopted the water clock or clepsydra, a device far older than Rome itself, originating in Egypt and Babylon. A clepsydra consisted of a stone or metal bowl with markings inside and a hole to let water drip out at a steady pace. The level of water indicated the hour. They were used in courts, military camps, and night vigils, anywhere sundials were impractical. One clepsydra on display in the British Museum shows refined calibration and use of numerals and lines etched in cinnabar.

These devices helped regulate time in an empire where precision increasingly mattered for law, religion, and military coordination.

Superstitions and Sacred Days

Who Had More Days Off?

One of the most surprising facts of historical timekeeping is just how much time off the ancients and medievals had compared to today’s modern worker. A typical modern office worker in the Western world might enjoy 25 to 30 days of holiday annually, but when factoring in weekends, this rises to about 129–134 days off per year.

A medieval peasant, however, often observed 80 to 100 days where work was either forbidden or significantly reduced due to religious feast days, saints’ days, and local festivals. Additionally, Sundays were days of rest, enforced more strictly over time by the Church. This could bring their total to 130 or more days of reduced labour, though within the constraints of agrarian hardship and seasonal demands.

A Roman citizen also enjoyed a significant number of holidays. By the late Republic and early Empire, the calendar contained around 120 public festival days (feriae), including religious rites, games (ludi), and civic observances. While not all these were full holidays for every citizen, they often suspended court sessions and political business.

So, while none of these societies enjoyed the modern concept of the "weekend," it's fair to say that medieval peasants and Roman citizens may have had more frequent holidays than many modern employees, though the experience of leisure was shaped very differently by their cultural and material worlds.

From Rome to the Middle Ages

The Julian Calendar persisted through the fall of the Western Roman Empire and became the bedrock of medieval timekeeping. Yet the medieval calendar was a patchwork of local customs, saints’ days, agricultural observances, and older pagan solstices.

In Christian Europe, Lady Days, the feasts of the Virgin Mary, became major calendar markers. The Annunciation (March 25th) was treated in many places as New Year's Day, as was Easter, Christmas, or January 1st, depending on region and century. This inconsistency created widespread confusion in legal and financial documents.

Equinoxes and Solstices continued to hold spiritual significance. Midsummer (the summer solstice), Yule (winter solstice), and the spring and autumn equinoxes were layered with Christian symbolism but retained their ancient power.

The practice of April Fool’s Day likely originated in the confusion surrounding New Year’s Day. Those who still celebrated New Year in March (Annunciation style) were mocked by those who had adopted the new Gregorian reckoning in January.

In the Roman calendar, New Year’s Day was originally March 1st, marking the start of the consular year. This lingered in usage even after the Julian reform, especially in legal contexts.

From Caesar’s blood-soaked arrival in Egypt to the dusty scrolls of the Library of Alexandria, from sundials and market days to saints and fools, the Roman understanding of time has shaped our own in ways both rational and mystical. Time in Rome was not merely a measurement, it was a ritual, a negotiation with the cosmos, a tool of empire and belief. And it continues, in curious fragments, to tick on, drip or cast it's shadow.

Related Articles

4 October 2025

The Ancient Blood: A History of the Vampire27 September 2025

Epona: The Horse Goddess in Britain and Beyond26 September 2025

Witchcraft is Priestcraft: Jane Wenham and the End of England’s Witches20 September 2025

The Origins of Easter: From Ishtar and Passover to Eggs and the Bunny12 September 2025

Saint Cuthbert: Life, Death & Legacy of Lindisfarne’s Saint7 September 2025

The Search for the Ark of the Covenant: From Egypt to Ethiopia5 September 2025

The Search for Camelot: Legend, Theories, and Evidence1 September 2025

The Hell Hound Legends of Britain25 August 2025

The Lore of the Unicorn - A Definitive Guide23 August 2025

Saint Edmund: King, Martyr, and the Making of a Cult14 August 2025

The Great Serpent of Sea and Lake11 August 2025

The Dog Days of Summer - meanings and origins24 June 2025

The Evolution of Guardian Angels19 June 2025

Dumnonia The Sea Kingdom of the West14 June 2025

Are There Only Male Angels?