Written by David Caldwell ·

The Leaping Terror: A Definitive History of Spring-heeled Jack

Introduction

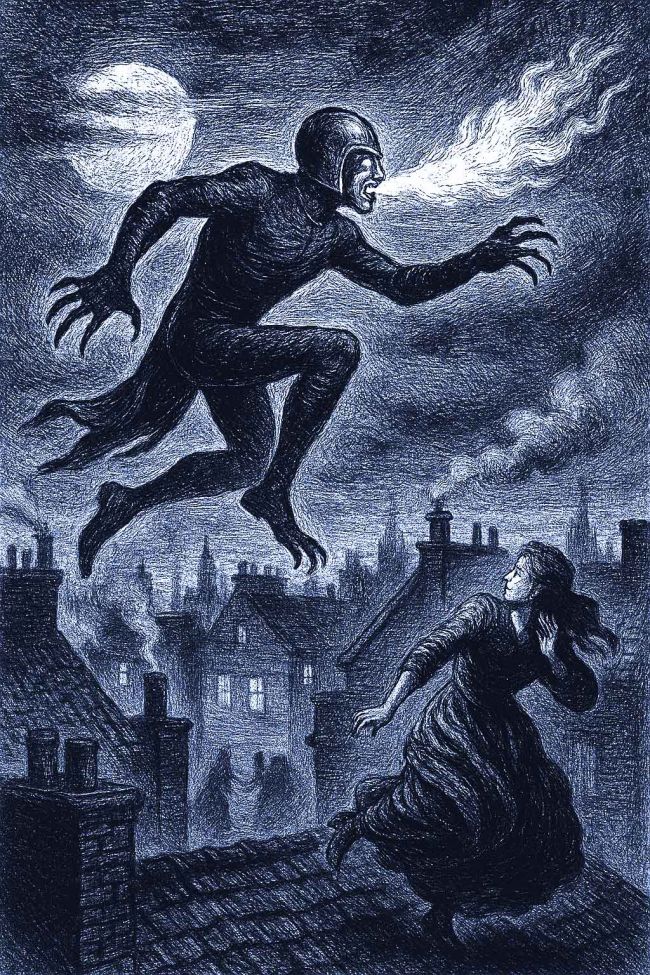

In the shifting shadows of Victorian London and beyond, one mysterious figure came to haunt the popular imagination: Spring-heeled Jack. Sometimes described as a demon, at other times as a prankster or a soldier gone rogue, Jack’s legend took hold in the 1830s and continued to spark sightings, scandals, and speculation well into the 20th century. This article pieces together the phenomenon using primary sources from across the British press, constructing a definitive timeline and examining the social context that gave rise to one of the most enduring phantoms of modern folklore.

Origins of the Name (1824)

The earliest known use of the term “spring-heeled” predates the terror itself by more than a decade, emerging not from folklore but from fashion. In The London Telegraph (15 November 1824), the phrase appears in a witty anecdote involving Lord Byron, who remarks on his friend’s preference for “a pair of Hobby’s best spring-heeled Jacks.” The line refers, not to a supernatural being, but to a finely made pair of boots - fitted with resilient soles or spring-steel heels, a novelty of Regency craftsmanship that promised elegance and agility in equal measure.

Hobby, a bootmaker of Lisle Street, Leicester Square, advertised in the late 1820s as a purveyor of “boots made from the skin of the seal,” combining “elegance with ease.” His clientele were the dandies and gentlemen of London society - the same milieu Byron moved in - who prized footwear that enhanced both comfort and posture. Around this period, bootmakers such as Hobby, Woolfield, and others in London and Birmingham were producing what they called spring-heeled boots or spring heels, a fashionable innovation in leatherwork designed to absorb impact and give a “light step.”

It is entirely plausible that this fashionable expression, once associated with grace and vigour, later resurfaced when newspapers sought a name for the mysterious leaping figure that terrorised London in the 1830s. “Spring-heeled Jack,” then, may have begun as a piece of Regency slang - a term for a nimble gentleman’s footwear - before becoming the nickname of a creature whose unearthly leaps seemed to mock that same image of human refinement.

Before Spring-heeled Jack was a monster, he was a pair of boots - elegant, agile, and aristocratic.

The First Wave: The Panic of 1837-1838

The legend as we know it begins in late 1837. The winter months saw repeated reports of an assailant attacking women in and around London, particularly in suburban areas such as Barnes, Hammersmith, and Blackheath.

Early Attacks

- November 1837 - Hammersmith: According to later retrospectives, laundresses and servants were terrified by a figure that could leap high fences, appeared at times like a baboon, at others like a cloaked man, and emitted an eerie growl.

- Blackheath: Women described being confronted by a “monster of phosphoric lustre,” with horns, claws, and fiery breath. The detail of “springs” in his boots was already being mentioned, giving rise to the moniker Spring-heeled Jack.

The Staffordshire Advertiser (24 February 1838) reprinted one of the earliest and most graphic accounts from London. It described Miss Alsop, aged 18, answering her door to a cloaked visitor who “vomited forth a quantity of blue and white flame” and whose “eyes resembled red balls of fire.” He wore a helmet and a tight-fitting suit “of white oilskin,” and attacked her with “claws of some metallic substance,” leaving her neck and arms lacerated. The account ends with the figure vanishing into the night, establishing the archetypal description that would haunt Britain for generations.

Mansion House Court, January 1838

A key moment came on 10 January 1838, when the Lord Mayor of London announced at Mansion House Police Court that he had received five letters describing the antics of a prowler who terrified young women. One described him as a man who appeared suddenly, often in disguise, breathing flames or wearing armor, and then escaped by leaping away. The Lord Mayor was skeptical, but public outrage was undeniable. A deputation of citizens demanded police action.

Newspaper Accounts

- London Courier and Evening Gazette (22 February 1838) reported the “Outrage on a Young Lady,” Miss Alsop of Lavender Hill, who was attacked by a man breathing fire and clawing at her gown. Her sister confirmed the assault.

- Patriot (22 February 1838) offered a similar account with grisly detail: Jack wore a helmet, breathed flames, and tore at Miss Alsop with metallic claws.

- Morning Herald (7 February 1838) noted that among ice-skaters in St James’s Park was “a person in black, who was named by the spectators as ‘Spring-heeled Jack.’” The figure was already becoming a subject of popular rumor.

Arrests and Hoaxes

Later in February 1838, two men - a bricklayer and a carpenter - were arrested at Lambeth Police Court for playing pranks in disguise, though they were eventually acquitted. Theatrical managers even testified about the chemical substances required to produce “blue and white flame.” The Civil & Military Gazette (28 May 1905), reflecting years later, described these trials as central to the hysteria of the time.

Mid-Victorian Encounters (1840s-1870s)

Though the initial panic subsided, reports of Jack never truly ended. Instead, they evolved geographically and stylistically.

Even in the 1850s, the figure reappeared under similar guises. The Bury and Norwich Post (7 December 1853) reported that in Gorleston, near Yarmouth, “a miscreant, by aid of spring-heeled boots, jumps over walls” to terrify women walking alone. Described as wearing a “hair-skin coat” with a jackass’s head, this local prankster blended rural grotesquery with urban legend - proof that Jack’s myth had spread well beyond London.

The Trickster at Large

Throughout the 1840s and 1850s, Jack’s appearances were sporadic. His image shifted from terrifying demon to practical joker, but always with an undercurrent of menace. By this time, he had become both a bogeyman to frighten children and a tabloid sensation.

The Aldershot Barracks Incidents (1877-1878)

The next great wave came decades later, this time in military settings.

- Cornishman (10 October 1878) and Carlow Sentinel (12 October 1878) both reported that a figure identified as Spring-heeled Jack was tormenting soldiers at Aldershot. Guards fired at him multiple times, but he was never hit. Descriptions emphasized his athleticism and uncanny leaping powers.

- He was described as a “tall, powerful man” with extraordinary pedestrian abilities, clad in oilskin or armor. Some reports suggested a soldier in disguise.

- Private Jackson of the 41st Regiment allegedly fired at Jack four times without effect.

These military sightings brought renewed seriousness to the legend. Jack was no longer only a prankster in London alleys; he was now a figure who humiliated the armed forces.

Regional Variations (1860s-1900s)

Windsor, 1885

The St James’s Gazette (23 January 1885) reported a sighting near Windsor. A policeman was attacked by a leaping assailant, who was caught but released with only a caution. Again, the strange leniency of the law in these cases added to the mystery.

Guernsey, 1897

The Guernsey Star (28 October 1897) described young men dressed in black and white with springs in their boots terrorizing pedestrians. Vigilantes captured one and beat him severely. Here, Spring-heeled Jack was clearly a fad among pranksters imitating the legend.

Jersey, 1893

The Jersey Express (14 September 1893) connected Jack to local lore in St Helier. Residents spoke of a leaping figure, while the writer compared him to “Slippery Jack” in Ontario, Canada, suggesting the legend had crossed oceans.

Early 20th-Century Memory and Folklore

By the dawn of the 20th century, Spring-heeled Jack had become a creature of retrospectives, half-remembered but still unsettling.

- Tower Hamlets Independent (11 June 1904) recounted his many disguises: white bull, baboon, steel-armored devil, and brass-clawed monster. The piece stressed that his true identity was never discovered.

- Orcadian (14 May 1904) carried a nearly identical retrospective, showing how newspaper lore repeated itself across regions.

- Norfolk Chronicle (15 September 1906) included Jack in a meditation on phantoms and Norwich ghost stories. Here, Jack was one of many folkloric “sprites” of an older England.

Between the Wars (1910s-1930s)

Jack’s legend did not die with the Victorians.

- Potteries Examiner (28 December 1878) had earlier speculated Jack was a soldier, but by the 1920s and 30s, writers increasingly linked him with pranks, hoaxes, and mischief.

- Lancashire Evening Post (12 October 1929) reported Stockport police believed Spring-heeled Jack to be nothing more than mischievous boys. Two youths were caught carving “S.H.J.” into a shop doorway.

- Linlithgowshire Gazette (3 January 1930) linked Jack to a Cheshire dog-poisoner and to a mysterious “Epping Ghost.”

By this stage, Jack was less a literal terror than a cultural shorthand for strange nocturnal mischief.

Later Reminiscences (1940s)

As late as 1942, letters in regional newspapers showed Jack’s grip on memory:

- In the Dumfries and Galloway Standard (23 May 1942), a man recalled a Spring-heeled Jack encounter in 1887, when his brother saw the figure leaping an eight-foot wall in the gloaming near St Michael’s New Cemetery. The parcel of groceries he carried was left untouched, suggesting the motive was fear, not theft.

This indicates that even a century after his supposed first appearance, the tale was still alive in oral history.

Analysis: Who (or What) Was Spring-heeled Jack?

Theories

- Aristocratic Prankster - Rumors abounded that a nobleman, even the Marquess of Waterford, might be responsible. His reputation for wild behavior fueled speculation.

- Military Hoaxer - The Aldershot sightings lend weight to the idea of a soldier or officer testing his daring against authority.

- Mass Hysteria - Many accounts fit the pattern of moral panic, where stories spread faster than facts.

- Copycats - By the 1890s, pranksters imitating Jack in costume were caught repeatedly.

The association between “spring-heeled” footwear and the Regency elite has given weight to the theory that Jack began as an aristocratic prank. Bootmakers like Hobby and Woolfield catered to men of fashion - the same circles that produced Byron, Brummell, and the Hell-Fire Club’s spiritual descendants.

The idea of a nobleman equipped with experimental boots and pyrotechnic tricks fits both the technology and temperament of the time. The Marquess of Waterford, notorious for drunken escapades and cruel humour, remains the most frequently accused.

Timeline Summary

- 1824 - “Spring-heeled Jacks” mentioned as boots (London Telegraph).

- 1837-1838 - First major wave of attacks in London; Mansion House letters, Alsop assault, public panic.

- 1840s-1850s - Sporadic sightings; legend spreads.

- 1877-1878 - Aldershot Barracks hauntings; soldiers fire on Jack.

- 1885 - Windsor policeman assaulted.

- 1893 - Jersey sightings; comparisons with Canada’s “Slippery Jack.”

- 1897 - Guernsey pranksters punished.

- 1904-1906 - Newspaper retrospectives fix Jack as folklore.

- 1929-1930 - Stockport police dismiss Jack as boys’ mischief.

- 1942 - Reminiscence of 1887 sighting in Dumfries.

Conclusion

Spring-heeled Jack is one of Britain’s strangest cultural spectres. Emerging from the slang of fashionable boots, magnified by scandal-hungry newspapers, and sustained by decades of sightings and copycats, he is part phantom, part prankster, and part social mirror. Jack is a story of how modern folklore is made: from boots to bogeyman, from panic to parody, from terror to nostalgia.

Even today, he leaps through the pages of history - not because he was ever caught, but because he perfectly embodied the fears, fancies, and fascinations of his age.

Related Articles

4 October 2025

The Ancient Blood: A History of the Vampire27 September 2025

Epona: The Horse Goddess in Britain and Beyond26 September 2025

Witchcraft is Priestcraft: Jane Wenham and the End of England’s Witches20 September 2025

The Origins of Easter: From Ishtar and Passover to Eggs and the Bunny12 September 2025

Saint Cuthbert: Life, Death & Legacy of Lindisfarne’s Saint7 September 2025

The Search for the Ark of the Covenant: From Egypt to Ethiopia5 September 2025

The Search for Camelot: Legend, Theories, and Evidence1 September 2025

The Hell Hound Legends of Britain25 August 2025

The Lore of the Unicorn - A Definitive Guide23 August 2025

Saint Edmund: King, Martyr, and the Making of a Cult14 August 2025

The Great Serpent of Sea and Lake11 August 2025

The Dog Days of Summer - meanings and origins24 June 2025

The Evolution of Guardian Angels19 June 2025

Dumnonia The Sea Kingdom of the West17 June 2025

The Roman Calendar, Timekeeping in Ancient Rome14 June 2025

Are There Only Male Angels?