Written by David Caldwell ·

Elmet A Brittonic Kingdom and Enclave Between Rivers and Ridges

Elmet was a small Brittonic kingdom that endured for roughly two centuries after the end of Roman rule. Its heartland lay on the magnesian limestone between the Wharfe, Aire and Ouse - a naturally defensible triangle where dry ridges, wet lowlands and difficult crossings shaped political choices. Although the written record is sparse, the landscape, early place-names, early medieval churches and a handful of reliable notices allow a coherent account of where Elmet was, how it formed, and why it disappeared.

This article sets Elmet in its physical setting; outlines the Roman and sub-Roman background; draws together the principal textual testimonies (Bede, early Welsh poetry, later hagiography) with enduring field evidence (entrenchments, fords, minster sites); and considers the kingdom’s absorption into Northumbria. It also notes how later memory - dedications to St Oswald, wapentake names, and “in-Elmet” place-names - preserved aspects of the older polity.

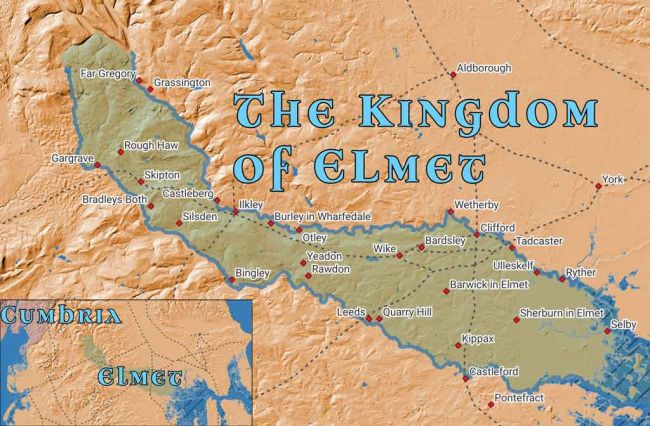

A map showing the location of Elmet, situated between the Rivers Aire and Wharfe

1) Physical geography: ridges, rivers and wetlands

Any realistic map of early medieval Yorkshire must begin with topography and hydrology, both very different in effect from the modern landscape.

- Ridges and dry ground. A narrow band of magnesian limestone runs north-east to south-west between the Wharfe and the Aire. It provides well-drained ground, abundant building stone and commanding views. Settlements, roads and later defensive earthworks repeatedly favour this spine.

- Wetlands as boundaries. Before large-scale drainage and canalisation, the lower Aire–Ouse basin was a mosaic of meres, marsh and floodplain carr. The lower Ouse and Humber formed broad, seasonally unpredictable waterways. Such wetlands were not marginal; they were strategic. They constrained movement, steered roads to high spurs, and separated political units as surely as any wall. In effect they placed York (Eboracum) on a dry island between river and marsh, and the Lincoln (Lindum) upland on a limestone escarpment with wet lowlands to north and east. In between lay extensive watery barriers that had to be skirted or crossed at known fords.

- Pennine backdrop. To the west the Pennines present a high, dissected upland. Valleys breaking east - Aire, Wharfe, Calder - carry routes and communities down to the lowlands. Elmet occupies the transition zone: a defensible ridge at the foot of the Pennine slope, looking across wet country to the Ouse.

These conditions explain why a compact, defensible polity could persist here after Rome. The rivers and wetlands created natural frontiers; the limestone provided the spine on which to organise defence.

2) Before Rome: later prehistoric occupation

Archaeology on the western and northern edges of the study area shows dense later-prehistoric activity:

- Grassington Moor / Cam Pasture / Bordley. Extensive field systems, ring-cairns and round-house platforms cover the moors above Wharfedale. Nineteenth-century maps label some rings “Druidical circle”; modern interpretation regards these as Bronze-Age ring cairns or small ceremonial circles, not Iron-Age temples. This upland is important long before Elmet, but it is not a Brigantian “capital”.

- Castleberg (Nesfield). A promontory fort above the Wharfe, locally significant, not Roman.

- Adel Moor and the Leeds ridge. Prehistoric hut circles and cup-and-ring stones occur on the high ground; a later Roman road (Tadcaster–Ilkley) runs close by. The ridge is repeatedly occupied in all periods because it is dry and strategically placed.

This background matters because later lines of defence and early church foundations often reuse, or sit adjacent to, long-established high places.

3) Roman period: a corridor on the Wharfe and a rural middle

The Roman military corridor is clear:

- Eboracum (York) anchors the regional network; Calcaria (Tadcaster) sits on the Wharfe; Isurium (Aldborough) lies further north; and Olicana/Ilkley (a Flavian-origin fort later rebuilt in stone) watches the Wharfe on the north-west fringe. Inscriptions record the Second Cohort of Lingones at Ilkley and altars to Verbeia, the river deity, with an associated civilian settlement (vicus). Anglo-Saxon crosses at Ilkley indicate later continuity.

- Between Wharfe and Aire the interior remained sparsely Romanised. Coin finds and occasional road traces show passage, but there is little sign of intensive imperial exploitation. The Romans preferred hard verges and dependable crossings; the wooded, clayey middle - where Elmet later cohered - remained largely rural.

- Claims of a Roman bridge near the Wharfe–Cock confluence (Kettleman’s Bridge) reflect long-standing crossing traditions at that point, whatever the precise date.

The effect is that Roman administration and movement shaped the northern edge of Elmet’s later heartland, while leaving the interior ecology and local organisation essentially intact.

4) Sub-Roman formation: Elmet as a defensive response (c. 410–600)

With imperial administration withdrawn in the early fifth century, Brittonic communities reorganised around defensible districts. In the Aire–Wharfe–Ouse triangle this produced Elmet.

Key features:

- Natural enclosure. The Wharfe to the north, Aire to the south and Ouse to the east present wide river obstacles, in parts bordered by wetland. The Pennine slope closes the western approach. Inside this enclosure the magnesian limestone provides a continuous dry crest.

- Linear earthworks. Along that crest run long, irregular banks and ditches commonly grouped under Aberford Dykes / Woodhouse Rein. Their precise dating varies by segment (late prehistoric to early medieval), but as a system they exploit the same logic: watch the fords, block the easy lines across the ridge, and fight with your back to dry ground. Subordinate scarps and short dykes appear elsewhere on the ridge (e.g., north of Kippax and Great Preston), reinforcing the picture of a defended spine.

- Internal water line. Cock Beck is the key internal stream, a shallow valley running below the ridge between Saxton and Aberford. Even today its fords are limited. As an obstacle inside the enclosure it adds depth to the defensive scheme.

- Settlement pattern and early churches. The later in-Elmet place-name cluster - Barwick-, Sherburn-, Saxton-, with medieval echoes of Micklefield-, Kirkby (Wharfe)-, Clifford- and Sutton-in-Elmet - sits precisely along the ridge and river margins where defence would focus. Early ecclesiastical traditions at Bardsey and Sherburn suggest that strong-points were quickly paired with minster-type churches. The sacral geography appears to inherit earlier strategic geography.

- Isolation through warfare. Battles in the early 7th century associated with Æthelfrith (e.g., near Chester) severed links between Brittonic polities in Gwynedd, Cumbria/Strathclyde and the Yorkshire interior. Elmet, between Deira on the east and the Pennines on the west, became increasingly isolated.

In short, Elmet is best understood as a landscape-driven polity: a small kingdom crystallising around a defensible ridge and using wetlands and rivers as outer walls.

5) Names, texts and chronology

Bede

The most authoritative written notice is Bede’s statement that King Edwin of Northumbria “expelled Ceretic/Ceredig, king of the Britons, from the region of Elmet” and took the land (usually dated 626–627). This establishes three critical facts: Elmet existed as a Brittonic kingdom; it had a named ruler; and it was annexed by Northumbria in the early 7th century.

Early Welsh poetry

Philological work aligns Welsh Elfed with English/Latin Elmet/Elmete. Poems of the “Old North” (the Gododdin corpus transmitted under Aneirin’s name, and pieces preserved in the Book of Taliesin) place Elfed within a matrix of northern Brittonic polities. Figures such as Gwallog ap Llaenog occur in praise poetry; later genealogical tradition remembers Ceredig ap Gwallog, which aligns - cautiously - with Bede’s Ceretic. These poems are not chronicles, but their onomastics and geographical hints are consistent with a compact Elmet on the Aire–Wharfe–Ouse axis whose borders had already contracted by the 620s. Modern reassessment by R. Geraint Gruffydd (In Search of Elmet, Studia Celtica 28, 1994) sharpens this picture, combining philology, place-names and careful reading of the verse.

Later hagiography (use with caution)

A late medieval Life of St Gildas states that his brother Mailoc/Maeloc came to “Luihes, in the district of Elmail”, built a monastery and died there. Edmund Bogg suggested the toponyms were corrupt and should read Loidis (Leeds) and Elmet, implying a monastery at Leeds within Elmet. The emendation is linguistically attractive - Loidis is the regular Latin for Leeds; Elmet/Elmete is well attested - but it lacks independent early corroboration and must be treated as conjecture. It is nevertheless a useful pointer to where one might look for early ecclesiastical foundations on the Leeds ridge.

6) Sites and lines on the ground

A concise gazetteer aids orientation:

- Barwick-in-Elmet. Massive earthworks and ringworks dominate the village, long seen as the probable politico-military centre in the kingdom’s final phase.

- Bardsey. Early ecclesiastical focus complementary to Barwick.

- Sherburn-in-Elmet. Royal/minster site with heavy later use: after Brunanburh (937) Æthelstan granted Sherburn and Cawood to the archbishops of York. The Hall Garth / Manor Garth complex immediately north of All Saints’ preserves platforms, banks and ditches of the archiepiscopal residence, demolished in 1361 for stone to build the choir of York Minster.

- Aberford Dykes / Woodhouse Rein. The principal linear earthworks along the limestone ridge above Cock Beck between Saxton and Aberford; subordinate scarps occur elsewhere on the ridge.

- Cock Beck. The internal defensive stream, running from Saxton/Towton Field towards Aberford; critical fords sit below the ridge.

- Kippax. Hall Tower Hill (motte/prospect mound), moated site and park pale of Kippax Hall (medieval). Short linear scarps on the ridge echo earlier defensive logic.

- Ilkley (Olicana/Verbeia). Roman fort on the Wharfe with altars to Verbeia; late crosses in the churchyard. Serves as the north-western hinge of movement along the river.

- Grassington Moor / Cam Pasture. Later-prehistoric field systems and ring-cairns; extensive lead-mining hushes of post-medieval date. Important in the long view but not an Iron-Age or sub-Roman capital.

- Castleberg (Nesfield). Prehistoric promontory fort; not a Roman camp.

- Dewsbury. Edge of Elmet where Bede’s account places Paulinus preaching and baptising in rivers; local tradition and carved stones in the churchyard preserve the memory.

This suite of sites shows how Elmet is read from the ground: the kingdom’s lines are still visible in ditches, fords and enduring church centres.

7) Annexation and after-history (c. 627 onwards)

Edwin’s annexation ended Elmet’s political independence. The physical structures and their uses evolved rather than vanished.

- Defences to boundaries. Banks and ditches that once divided war-bands often became parish, township or wapentake lines. The infix in-Elmet persisted in place-names as a quiet record of earlier identity.

- Ecclesiastical continuity. Sites such as Bardsey, Sherburn, Ledsham and Saxton show early ecclesiastical fabric or traditions; churches continued to occupy commanding or long-used positions on the ridge, effectively re-sanctioning a defensive landscape.

- St Oswald and the re-mapping of memory. Within a decade of annexation Oswald - reared in exile at Iona - restored and expanded the Christian mission from Lindisfarne. Dedications to St Oswald at Guiseley and Methley, and the former Oswaldcross wapentake at Pontefract, show how the district’s religious and administrative map adopted Anglian royal saints. This did not obliterate earlier Brittonic Christianity, but absorbed it into a Northumbrian narrative.

- Winwæd. The great battle of 655, in which Oswiu defeated Penda of Mercia, is placed by later Yorkshire tradition at Whinmoor/Winn Moor, on the limestone near Barwick-in-Elmet. Other locations have been suggested; the identification should be presented as traditional rather than proven. If correct, it would mean that the ridge which once guarded Elmet also witnessed the decisive Northumbrian–Mercian reckoning.

8) York, Lincoln and the wetland divide

The geography that sustained Elmet also shaped the fates of York and Lincoln in the post-Roman centuries:

- York sits on a gravel terrace beside the Ouse. In late and immediately post-Roman times, extensive wetlands to east and south constrained movement. Control of ford and causeway approaches - particularly from the west via Tadcaster/Wharfe and from the south via the Aire–Ouse - was strategic. The Wharfe corridor (Ilkley–Tadcaster–York) remained vital; the defended ridge of Elmet lay between York and the Pennine routes.

- Lincoln occupies a limestone ridge above the Witham valley. To its north-west lay low wet country and the wide Trent/Humber system. In the early medieval period, water discouraged direct overland movement between the two old cities except at known corridors. Elmet’s location on dry ground among these watery obstacles is one reason it could persist as a separate jurisdiction for as long as it did.

Understanding these wetlands as functional frontiers helps explain the survival of small polities in northern and eastern Britain in the fifth to seventh centuries.

9) A note on names and modern misreadings

- Ben Rhydding (Ilkley). The settlement east of Ilkley, originally Wheatley, took the name Ben Rhydding from the hydropathic establishment opened in 1844. The form looks Welsh (pen, rhyd), but in practice it is a Victorian coinage/branding that likely plays on northern ridding (“clearing”). It should not be used to infer a Welsh-speaking enclave.

- “Roman camps” on old maps. Nineteenth-century sheets sometimes label earthworks generically as “Camp” and small rings as “Druidical.” Many such features around Grassington and Nesfield are prehistoric (or even post-medieval mining) rather than Roman.

These clarifications matter because Elmet research relies on consistent reading of terrain and toponyms: later romantic labels can mislead.

10) Summary: what Elmet was

Elmet was a Brittonic kingdom that formed after Rome within a triangle of rivers - the Wharfe, Aire and Ouse - whose wetlands and wide channels acted as outer defences. A narrow magnesian limestone ridge provided the kingdom’s spine, still legible today in the line Barwick–Aberford–Saxton–Sherburn, above the internal water obstacle of Cock Beck and guarded by long earthworks (Aberford Dykes/Woodhouse Rein). The polity probably began larger and contracted under Anglian pressure. It was Christian by the early seventh century, and Bede records its last known ruler, Ceretic/Ceredig, expelled by King Edwin c. 626–627. Thereafter the landscape was re-inscribed by Northumbrian Christianity (notably through St Oswald), and by ecclesiastical and administrative structures that adopted the old strong-points. The name endured in in-Elmet place-names; aspects of its legal and religious memory persisted in Oswald dedications and in the Oswaldcross wapentake.

11) Working bibliography (for orientation)

- Bede, Historia Ecclesiastica Gentis Anglorum - principal historical notice of Elmet’s annexation; accounts of Paulinus, Oswald and Oswiu relevant to the district.

- Early Welsh poetry (the Gododdin corpus; poems in the Book of Taliesin) - onomastic and geographical references to Elfed, Gwallog and the “Old North”; to be used cautiously as historical evidence.

- R. Geraint Gruffydd, “In Search of Elmet,” Studia Celtica 28 (1994), 63–79 - modern philological and onomastic reassessment of Elmet’s name, location and context; argues for a core on the Aire–Wharfe–Ouse axis and a contracting frontier.

- Edmund Bogg, The Old Kingdom of Elmet (1902/1904) - antiquarian but valuable for detailed topographical observations (Aberford Dykes, Cock Beck crossings, Sherburn church and Hall Garth). Includes the emendation of “Luihes in Elmail” to “Loidis in Elmet” (plausible but unproven).

- Local historical notices and lectures (late 19th–20th c.) - preserve early traditions: Paulinus at Dewsbury; St Oswald dedications at Guiseley and Methley; Oswaldcross wapentake; and summaries of the Barwick–Aberford–Saxton earthworks.

12) Practical mapping notes

For readers visualising Elmet:

- Show a core zone (solid tint) within the Wharfe–Aire–Ouse triangle, and an outer possibility (lighter wash) westwards towards Ilkley and south towards the Don to reflect antiquarian and philological reconstructions.

- Emphasise Cock Beck and the Aberford Dykes/Woodhouse Rein, with Barwick, Bardsey and Sherburn as major nodes.

- Mark Ilkley, Tadcaster and Aldborough to clarify the Roman corridor; and indicate wetlands around the lower Aire–Ouse–Humber to show how water separated polities and conditioned access to York and Lincoln.

- Include the in-Elmet toponym cluster as evidence points.

Elmet can be reconstructed without romanticising. Its existence is a measured inference from the terrain, a small number of reliable texts, and enduring place-names and earthworks. In a landscape where wetlands divided as much as hills, Elmet’s ridges and rivers explain its appearance, its persistence and its eventual absorption into a larger Northumbrian order.

Related Articles

8 November 2025

How the Conquering Sun Became the Conquering Galilean24 October 2025

The Ebionites: When the Poor Carried the Gospel12 October 2025

Queen of Heaven: From the Catacombs to the Reformation4 October 2025

The Ancient Blood: A History of the Vampire27 September 2025

Epona: The Horse Goddess in Britain and Beyond26 September 2025

Witchcraft is Priestcraft: Jane Wenham and the End of England’s Witches20 September 2025

The Origins of Easter: From Ishtar and Passover to Eggs and the Bunny12 September 2025

Saint Cuthbert: Life, Death & Legacy of Lindisfarne’s Saint7 September 2025

The Search for the Ark of the Covenant: From Egypt to Ethiopia5 September 2025

The Search for Camelot: Legend, Theories, and Evidence1 September 2025

The Hell Hound Legends of Britain25 August 2025

The Lore of the Unicorn - A Definitive Guide23 August 2025

Saint Edmund: King, Martyr, and the Making of a Cult14 August 2025

The Great Serpent of Sea and Lake11 August 2025

The Dog Days of Summer - meanings and origins24 June 2025

The Evolution of Guardian Angels19 June 2025

Dumnonia The Sea Kingdom of the West17 June 2025

The Roman Calendar, Timekeeping in Ancient Rome14 June 2025

Are There Only Male Angels?