Written by David Caldwell ·

The Hell Hound Legends of Britain

Shadows on the Lanes

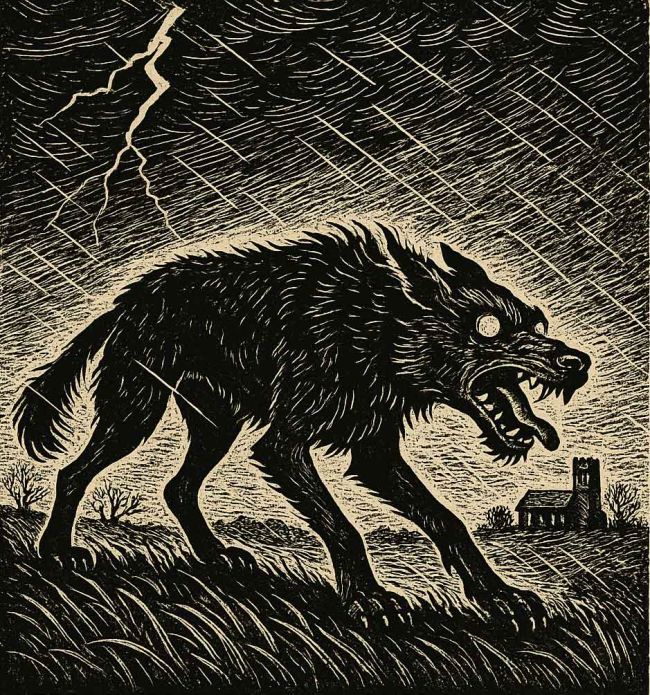

Across the lonely lanes, churchyards, and coastal paths of England, the legend of the hell hound has stalked the imagination for centuries. Known variously as Black Shuck, Old Shuck, the Barghest, Padfoot, or even the Galleytrot, this monstrous black dog is said to appear on stormy nights, its eyes blazing like coals, its breath reeking of fire and brimstone.

For those who encounter it, the hound is no ordinary beast. Its appearance is traditionally regarded as an omen of death, a spectral warning that either the witness or someone close to them will perish within the year. Villagers whispered that to hear its howl on the moors was to invite disaster. Farmers, fishermen, and travellers knew its name with dread.

Though stories of phantom hounds exist across the British Isles, it is in Norfolk, Suffolk, Cambridgeshire, Yorkshire, and the North Country that the Black Dog?s reputation is strongest. These regions still preserve the memory of its hauntings, tied to place-names, ruined churches, and village lore.

Origins in Norse Myth

Folklorists often trace the roots of Black Shuck to the Scandinavian invaders who settled in East Anglia. The Norse brought with them the image of Odin?s hounds, spectral beasts who prowled storm clouds and carried the souls of the dead. In Norfolk dialect, the word shuck is connected to ?shucky,? meaning shaggy or demonic, and is also tied to the Anglo-Saxon scucca - ?demon? or ?evil spirit.?

One Norfolk writer described the phantom dog?s presence vividly: ?With eyeballs glowing like hot coals, teeth phosphorescent in the darkness, and a chain around its neck clanking a horrible melody?? Its appearance was sometimes accompanied by lightning and thunder, strengthening the association with storm deities and the Wild Hunt.

Like its cousin the Moddey Dhoo of the Isle of Man - a black spaniel that haunted Peel Castle - Black Shuck seems to embody the deep-rooted belief in spectral hounds as guardians of liminal spaces: crossroads, churchyards, and the boundary between land and sea.

Bungay and Blythburgh: The Storm of 1577

The most famous of all Shuck stories took place in August 1577, during a violent storm that struck the churches of Bungay and Blythburgh in Suffolk.

At St. Mary?s, Bungay, worshippers gathered for Sunday service when a flash of lightning plunged the church into darkness. According to Abraham Fleming, who recorded the event, a monstrous black dog ran down the nave, striking two men dead and scorching others. The claw marks Shuck left on the wooden north door, known locally as the ?Devil?s fingerprints,? can still be seen today.

On the same day, at nearby Blythburgh, the phantom reappeared. Witnesses said it burst through the church doors with a thunderous crash, leaving deep burns on the door and killing more parishioners before vanishing into the storm. The historian Stowe, writing soon after, declared: ?Immediately thereupon there appeared in a most horrible similitude and likeness to the congregation a black dog, together with fearful flashes of fire, which moved such admiration that they thought doomsday had already come.?

These twin events cemented Black Shuck?s place in East Anglian folklore, linking him with the supernatural violence of thunder, fire, and divine judgment.

Regional Variations of the Hell Hound

While the name Black Shuck is most often tied to East Anglia, the phantom hound takes many forms across Britain. Each region has its own name for the same terrifying archetype: the black dog that walks the night.

Norfolk and Suffolk: Shuck and the Galleytrot

In Norfolk and Suffolk, Shuck is most vividly remembered. Along the coast he stalks lonely beaches and churchyards, and in the fenland he is said to rise from the waters of Wicken Fen or prowl the Peddars Way, the ancient pilgrims? road. A 1929 newspaper even reported a ?phantom bear? with red eyes and a dog?s bark chasing men across fields at Buckenham Tofts - later explained by folklorists as another face of Black Shuck.

Further inland, he becomes the Galleytrot, especially in Suffolk. Geldeston churchyard is still called the ?place of the Hell Beast,? where he is said to frighten travellers on the Bungay?Beccles road.

Yorkshire: The Barghest

In the Yorkshire dales, the hound appears as the Barghest - a massive black dog with glaring eyes and breath like fire. It haunts lonely moorland paths and is said to bring death to those who see it. Villagers in Swaledale once told how a sceptic set out with guns to rid the district of the ghostly terror, only to be found dead the next day on the moors. Local lore declared it was the Barghest that had taken vengeance.

Another Yorkshire tale tells of the Padfoot, a huge white creature resembling a calf, which follows lonely travellers at night. Though it never attacks, it is still regarded as an omen of misfortune.

Wales: The Gwyllgi

The Welsh hills have their own equivalent - the Gwyllgi, literally ?the dog of darkness.? Like Shuck, the Gwyllgi is a great black beast with fiery eyes, stalking lonely roads and mountain paths. Folklorists note how closely this mirrors the English tales, suggesting a shared Celtic and Norse inheritance.

Other Phantom Hounds

Elsewhere in Britain, other spectral dogs carry the same themes. In Cambridgeshire, locals told of a ghostly hound that haunted Spinney Bank and the fens near Wicken. In Somerset, sightings were reported as late as the 1950s. In Ireland, similar tales survive of demonic dogs and fairy hounds, while the Isle of Man preserves the legend of the Moddey Dhoo, a black spaniel haunting Peel Castle, said to bring death to soldiers who challenged it.

The persistence of these regional names and forms suggests not isolated myths, but a deep-rooted belief across the British Isles: that a black hound walks with us in the dark.

Haunted Places and Local Legends

Every county seems to have its own Shuck Lane, Hellhound?s Walk, or tale of a phantom dog at a ruined church or coastal track. A few stand out as especially rich in folklore:

- Beeston and Overstrand, Norfolk: The dreaded ?Shuck Lane,? where a chain was heard clanking on stormy nights.

- Stiffkey, Norfolk: Locals described Shuck as ?big as a donkey, black as pitch, with eyes like bikelamps.? Stiffkey?s reputation was so great that it entered print in the Daily Express.

- Dunwich Abbey: Said to be haunted by Shuck during the Twelve Days of Christmas, when spirits were believed to walk most freely.

- Coltishall Bridge, Norfolk: Another favoured haunt, where villagers swore they heard his howl above the roar of the wind and sea.

- Market Hole, near Norwich: One man swore he saw Shuck appear beside his bicycle and pass straight through the frame.

- Spinney Abbey, Cambridgeshire: Site of a monk?s murder centuries ago, remembered as a place where a spectral hound emerged from the fenland mist.

These sightings were not restricted to the Middle Ages. As late as the 20th century, newspapers reported encounters, gamekeepers told of their dogs fleeing in terror, and councillors in Bungay debated whether Black Shuck should appear on the town?s heraldry.

The Symbolism of the Hell Hound

An Omen of Death

Above all, the Black Dog was an omen of mortality. To see him was to receive a warning - often that the witness would die within the year. This idea echoes through the stories: the Bungay and Blythburgh church disasters of 1577, the Yorkshire Barghest striking down a sceptic on the moors, or the phantom hound that appeared to cyclists and gamekeepers in Norfolk, leaving them shaken for life.

Even when Shuck did not kill directly, he struck terror into those who saw him. In one tale, he passed through a rider?s bicycle as if through mist. In another, he leapt through a church congregation, searing men as though their skin had been scorched in fire. His appearance was a grim reminder that life was fragile and death could arrive unbidden.

Guardian of Boundaries

The hell hound is also closely tied to boundaries - both physical and spiritual. He prowls churchyards, crossroads, bridges, coastlines, and fen paths: all liminal places where the human and the supernatural intersect.

This association reflects ancient beliefs that such spaces were dangerous thresholds, places where spirits gathered and the veil between worlds was thin. Shuck was not simply a beast of the wild; he was the guardian of places where one might slip into another realm.

Pagan Echoes and the Wild Hunt

Many folklorists connect Black Shuck to Odin?s hounds and the Wild Hunt, the storm-riders of Norse and Germanic myth. These spectral packs pursued souls across the sky, their howls heard in winter gales. The very word Shuck derives from the Anglo-Saxon scucca, meaning demon or devil, reinforcing the Norse and pagan roots of the belief.

The ?phantom bear? sighting at Buckenham Tofts in 1929 - a beast with red eyes and a dog?s bark - recalls another link to Odin, who was also associated with bears and wolves. To East Anglians steeped in Norse heritage, a fiery-eyed hound on the road in a thunderstorm was no mere dog, but a visitation from the old gods.

Christian Fear and Demonisation

As England became Christian, the old tales of Odin?s hounds blended with church warnings of Hell. Shuck became a Hellhound, a servant of the Devil, his fiery eyes a mark of infernal origin. Accounts often describe him appearing in churches, striking down worshippers, or leaving claw marks on doors - a clear symbol that the powers of darkness could intrude even upon consecrated ground.

Some suggested these tales were used as religious propaganda. In the turbulent years after the Reformation, a phantom dog striking Protestant worshippers might be interpreted as a Catholic plot or a divine warning. Others saw the stories as parables against scepticism: to mock the supernatural was to invite its wrath.

Black Shuck in Modern Memory

Later Sightings

Though often thought of as a medieval or Tudor superstition, sightings of the Black Dog persisted well into the 19th and 20th centuries.

- In Somerset in 1957, witnesses reported a black hound as large as a calf, causing a minor sensation in the local press.

- In Cambridgeshire, near Spinney Bank and Wicken Fen, gamekeepers told how their well-trained dogs would tremble and flee from invisible terrors.

- In 1929, the so-called ?phantom bear? of Buckenham Tofts - red-eyed and growling like a dog - chased sober men across ploughed fields before vanishing, later reinterpreted as Shuck in disguise.

- Even cyclists in the early 20th century swore they had encountered the beast on lonely Norfolk lanes, watching as it passed clean through the frame of a bicycle like smoke.

In Bungay, the legend became so ingrained that in 1953 the town council officially placed Black Shuck on its heraldry, describing him in Latin as ?the Black Dog courant proper upon a flash of lightning.? Not everyone approved. Some townsfolk felt it unwise to elevate the hell hound to civic emblem, fearing it would only strengthen his power.

From Folklore to Literature

The legend of the spectral hound has inspired countless writers. Most famously, Sir Arthur Conan Doyle drew upon tales of the Black Dog of Dartmoor when crafting The Hound of the Baskervilles (1902). But references stretch further back: Richard Jefferies recorded local sayings about Shuck in the 19th century, while older chronicles and ballads speak of the ?Hellhound? and ?Snarleyow.?

Even today, ghost hunters and folklorists trace the paths of Shuck. Books, songs, and television documentaries continue to retell his story, often linking him with broader European legends of the Wild Hunt.

Why the Legend Endures

What explains the persistence of the hell hound? Perhaps it is the way the stories combine the terror of the wilderness with the mystery of death. For those who lived in rural East Anglia, storms could destroy crops, floods could drown villages, and disease could sweep away families overnight. The phantom dog became a face for these unseen forces - a reminder that life was fragile, that the dark might claim you at any moment.

At the same time, there is something strangely comforting about Shuck. He is feared, but he is also familiar, walking the same lanes as farmers, fishermen, and travellers. He is woven into the very landscape: into Shuck Lanes, into the claw marks on Bungay?s church door, into the memory of every villager who claimed to see eyes like burning coals staring back at them from the night.

Conclusion

From the churches of Bungay and Blythburgh, where lightning and fire once revealed him, to the coastal paths of Norfolk, where fishermen still whisper his name, Black Shuck remains one of Britain?s most enduring phantoms.

He is at once an omen of death, a survival of pagan myth, and a figure of Christian demonology. But above all, he is a story - told and retold for centuries, carrying with it the collective fears and imaginations of those who walked lonely lanes in the dark.

Even today, if you find yourself on a stormy night by the Waveney, the Broads, or the wind-swept coast of East Anglia, take care where you tread. For the old people still say:

?Woe betide the one who meets Black Shuck, the dread hound of the night.?

Related Articles

8 November 2025

How the Conquering Sun Became the Conquering Galilean26 October 2025

Elmet A Brittonic Kingdom and Enclave Between Rivers and Ridges24 October 2025

The Ebionites: When the Poor Carried the Gospel12 October 2025

Queen of Heaven: From the Catacombs to the Reformation4 October 2025

The Ancient Blood: A History of the Vampire27 September 2025

Epona: The Horse Goddess in Britain and Beyond26 September 2025

Witchcraft is Priestcraft: Jane Wenham and the End of England’s Witches20 September 2025

The Origins of Easter: From Ishtar and Passover to Eggs and the Bunny12 September 2025

Saint Cuthbert: Life, Death & Legacy of Lindisfarne’s Saint7 September 2025

The Search for the Ark of the Covenant: From Egypt to Ethiopia5 September 2025

The Search for Camelot: Legend, Theories, and Evidence25 August 2025

The Lore of the Unicorn - A Definitive Guide23 August 2025

Saint Edmund: King, Martyr, and the Making of a Cult14 August 2025

The Great Serpent of Sea and Lake11 August 2025

The Dog Days of Summer - meanings and origins24 June 2025

The Evolution of Guardian Angels19 June 2025

Dumnonia The Sea Kingdom of the West17 June 2025

The Roman Calendar, Timekeeping in Ancient Rome14 June 2025

Are There Only Male Angels?