Written by David Caldwell ·

The Knights Templar: Heresy, Cats, and the “Head” - Rereading an Order We Thought We Knew

Prologue: What if the “warrior monks” were learners first?

The Knights Templar live rent-free in the Western imagination. To some they are the prototype of the international banker, to others the custodians of an occult current opposed to Church and crown, to others still a convenient morality tale about greed and royal jealousy. But what if another thread-obvious in scattered sources once you join them-has been hiding in plain sight? What if the Templars were less a satanic cult with a secret idol, and more a brotherhood that absorbed knowledge and practices encountered in the Islamic world-and then paid the price for looking east rather than only west?

This essay follows the Templars from their ordinary, almost unimpressive birth in Jerusalem, through their dizzying reach across Europe, into the furnace of accusation and trial, and out again into the cold air of dispersion and legend. Along the way we’ll test the Baphomet riddle, a now-forgotten “cat theory” of heresy, Victorian re-readings of the whole affair, and the stubborn belief that remnants sailed to Scotland and Ireland to fight under Robert the Bruce. Our aim is not to debunk the orthodox story so much as to widen it, and to let some neglected possibilities back into the light.

I. Humble origins at the edge of empire

The first Templars were not titans. Around 1119/1120, Hugues de Payens and a handful of companions vowed to protect pilgrims on the perilous roads of the newly conquered Kingdom of Jerusalem. Their “headquarters,” such as it was, sat on the Temple Mount-hence their formal title, the Poor Fellow-Soldiers of Christ and of the Temple of Solomon. Only later would the white mantle with the red cross (authorized after 1148) become a European status symbol, restricted to those of knightly birth.

Bernard of Clairvaux’s advocacy in the 1120s gave the little militia a theological chassis. What followed was a long, practical apprenticeship in administering risk at the frontiers: convoying pilgrims through bandit country, maintaining castles and outposts, negotiating with Muslim rulers for safe passage when force made poor sense, keeping custody of travelers’ valuables, and-eventually-moving money by paper instead of by packhorse. What crusade narratives call “zeal,” account books call “infrastructure.”

By mid-century, papal exemptions released the Order from tithes and episcopal jurisdiction. A node in France could answer directly to a commander in Jerusalem and ultimately to the Grand Master; a priory in England could advance funds against revenues in Aragon. In the dry language of a local newspaper many centuries later, the Order “established the world’s first formal credit system” and ran a continent-wide logistics chain of lodges, ships, and granaries. That precision-and the independence it bought-bred admiration and resentment in equal measure.

II. Power as a spiritual problem

Templars took monastic vows, but they lived like soldiers. They were expected to fast, to confess, to avoid women-and to fight, ride, and kill. The mixture makes theological sense in a Bernardine age: penitence through combat, poverty through corporate wealth, purity amidst tents and carnage. But that hybrid life exposed them to the very temptations their rule tried to fence out. Medieval critics did not have to invent pride or avarice among Templars; they only had to notice them.

By the late thirteenth century, the Order’s balance sheet was formidable and its political value ambiguous. Kings borrowed from them; bishops complained they answered only to Rome; refugees from the last Levantine catastrophes wanted pay and purpose. The Templar model-mobile capital, permanent exemptions, and a pan-European brand-looked less like a crusading tool and more like a rival jurisdiction.

It is here that narrative often snaps straight to 1307 and a greedy Philip IV. The “jealous king” explanation is tidy, but it cannot do the whole job. Accusations need a cultural soil to sprout in, a vocabulary of suspicion. That vocabulary had been evolving for centuries.

III. What, exactly, were they accused of?

The bill of particulars assembled in France after the mass arrests of Friday, 13 October 1307 is infamous: spitting on the cross during initiation, kissing obscenely, denying Christ, worshipping a mysterious head or idol, and committing “unnatural vices.” Variants proliferated-mock masses, cat worship, sorcery. A great deal of this was extracted under torture, and a great deal contradicts itself when the threat is removed. But the clustering is instructive. Three themes dominate:

Reversed ritual: A deliberate humiliation of Christian symbols-spitting on the crucifix, trampling the host, renouncing Christ’s divinity.

Improper bodies: Sexualized kisses at the base of the spine or on the mouth, sodomitical acts.

Forbidden images: A head-sometimes bearded, sometimes with multiple faces, sometimes female-venerated in secret.

Seen from a distance, this looks less like a detailed ethnography of Templar practice and more like a medieval “grab-bag” of charges reliably used to blacken an enemy: the same cocktail thrown at early Christians by pagans, at Jews in Christian cities, at witches later on. One sharp Victorian reviewer noted that in “all these cases, heretical opinions and monstrous vices are coupled together, as if one implied the other.” The formula was off-the-shelf.

Even so, two strands deserve patient attention because they echo realities the Templars actually lived with: Baphomet and the cat.

IV. Baphomet, Mahomet, and what a misspelling can hide

Baphomet enters history through depositions; it exits through centuries of speculation. In the French trial records the word hovers between idol and cipher. Later writers made of it everything from a goat-headed demon to the key to a lost gnostic rite. But nineteenth- and early twentieth-century observers-less bewitched by occultism than many today-were blunt: “Baphomet is only Mahomet badly spelt,” said one London daily; the name, wrote another, was “probably a corruption of that of Mahomet,” the common medieval Latinization of Muhammad.

That prosaic possibility matters. If the interrogators heard Mahomet where a Templar mentioned Muhammad (or if hostile witnesses deliberately used the crusader slur), then the alleged “idol” shrinks from demon to mishearing-from a horned head to a name spoken in the wrong company. Add to this the order’s long habit of practical dealings with Muslim powers-truces, ransoms, safe-conducts, resale of captives, even local accommodations in dress and language-and you have a credible source for a thin thread of “Eastern” teaching moving west along Templar lines of communication.

That hypothesis hardly requires a secret cult. A knight who had sworn on the Qur’an to secure a truce, or who admired a Muslim scholar’s astronomy, or who found the Prophet’s critique of Christian image-worship disturbingly sharp, might speak in ways that sounded like unbelief back in Paris. A scribe writes “Baphomet.” A judge supplies horns.

Victorian and Edwardian writers who revisited the affair-stripped of the rage of the trials-often came to similar conclusions: the Order as such was not diabolical; many confessions were tortured; “head” stories multiply in inquisitorial settings; and the Baphomet problem is philology more than demonology. Even harsh critics of Templar pride conceded that the official case could not stand in a neutral court. Against baroque occult reconstructions, sober voices kept repeating: the simplest reading is probably the right one.

V. The cat, the heretic, and how language remembers fear

Then there is the cat. In German, Ketzer means “heretic.” A curious etymology, recorded in nineteenth-century essays and provincial papers, notes a long-standing folk link between Katze (cat) and Ketzer: Waldensians and Albigensians were mocked as cat-worshippers; even Templars were said to adore a “large black cat.” In parts of Italy, cats on roofs in February were thought to be witches in disguise-game for stones or arrows. We are a long way here from Parisian trial minutes, but we are deep inside the medieval palate of suspicion in which the Templar case was seasoned.

What to do with such lore? At minimum it shows how easily any “secret” fraternity could be painted with the same brush used on witches: reversed crosses, obscene kisses, animal familiars. Once the Templars had been publicly accused, old images came to the surface: heads, goats, cats-anything the crowd could picture. Modern readers should hear the echo of older scapegoats in the Templar dossier.

VI. Heads that talk and reliquaries that don’t

What about the “head”? Medieval Europe loved heads-saints’ skulls in silver cases, John the Baptist’s face painted on cloth, talking heads in romances. Some Templars did indeed keep reliquary heads; so did their neighbors. The leap from reliquary to idol is a short one when prosecutors need a narrative. Later romantics embroidered the tale with the Baptist’s severed head; commentators in 1930s newspapers coolly repeated that “the Saracen’s Head” signs in Britain were “reminiscences” of Baphomet-more myth folding into myth.

Strip the embroidery away and a commonsense picture remains: an order steeped in relic-culture is accused of having a relic that speaks-because that is what enemies say when they want your relics taken away.

VII. How the nineteenth century changed the file

If you read the case through Victorian eyes, the baseline shifts. Anglican and Catholic historians, working without royal pressure and with a rising taste for source criticism, often acquitted the Order of the worst charges. One authoritative dean gave a thin but devastating account: the Order’s wealth, pride, and political uselessness after 1291 made it vulnerable; the claims of blasphemy and sodomy rest on coerced confessions; the “mystical” reconstructions that turn Templars into custodians of perennial gnosis rest on air. Another reviewer mocked the way “Gnostic mysteries” and “Baphomet” theories let writers make the Templars into whatever they needed them to be.

This was not hagiography. Many nineteenth-century scholars were frank that the Order could be brutal and vain; that some men surely sinned; that corporate righteousness was unlikely in a brotherhood of armed monks. But they insisted on a distinction medieval prosecutors blurred: between the vices of individual Templars and the doctrine of their Order. That distinction-now basic to historical method-was precisely what royal policy in 1307 forbade.

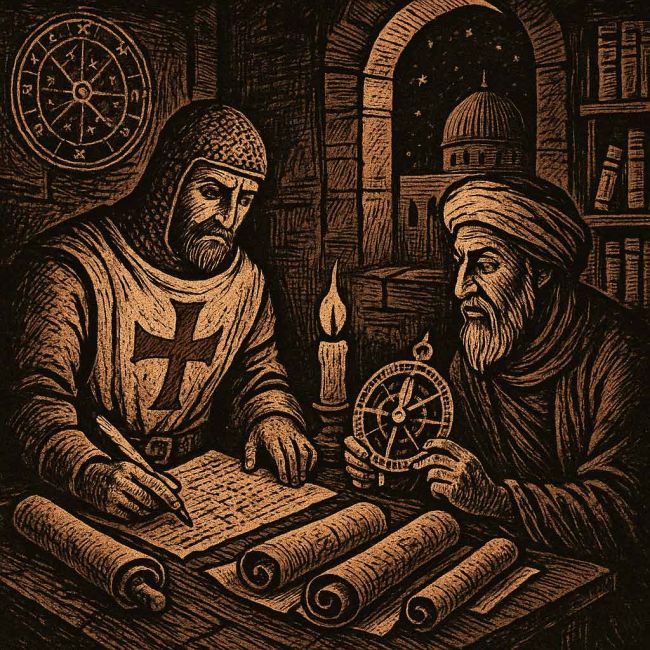

VIII. Islam in the background: contact, imitation, and threat

Return, then, to the “misspelling” and its implications. If Baphomet - Mahomet, then the most interesting “heresy” in the Templar file might not be witchcraft at all, but a kind of informal Islamicate acculturation-knowledge, habits, and phrases picked up in long contact with Arabic-speaking societies.

Historical commonplaces suddenly look different:

Pragmatic truces and safe-conducts: A soldier who sees honest dealing across a frontier can unlearn convenient hatreds.

Dress and demeanor: Chroniclers noted fraternization, borrowed garments, shared meals. Outsiders saw “adoption of Saracen ways.”

Science and craft: Navigation, court medicine, fortification, and astronomy were flourishing in the Islamic East while Europe relearned them. Military orders sat at those ports of transfer.

Is this “heresy”? To certain audiences in 1307, yes. A brother who admits that Muslims possess truths worth learning threatens a neat crusader worldview. An order that had once defined itself against the infidel can look compromised when it negotiates too well, reads too widely, or prays too quietly. The line between prudence and betrayal moves with the politics.

Here is a provocative inversion: modern far-right mythologizing casts the Templars as archetypal warriors against Islam. The record admits an alternative: that some Templars were unusually ready to acknowledge and use Islamic knowledge. If the Order harbored a “heresy,” perhaps it was competence without prejudice.

IX. Suppression, executions, and a curse that never dies

The machinery of destruction is well known. Philip IV coordinated arrests; inquisitors collected confessions; Pope Clement V, after hesitation and pressure, shifted from inquiry to suppression. In 1314 the last Grand Master, Jacques de Molay, was burned in Paris. Legend says he cursed king and pope; within a year both were dead. The line between poetic justice and coincidence has never been policed.

What followed in Europe was administrative more than dramatic: properties transferred to Hospitallers or to the crown; pensions for some brothers; prison or pyre for others. The brand “Templar” went dark, only to blaze again in secret-society lore, Protestant polemic, Catholic cautionary tales, and-much later-popular fiction. Even Victorian temperance groups adopting the name “Good Templars” found themselves denounced in print by a Catholic bishop as if the medieval file had been reopened.

X. Dispersal: Scotland, Ireland, and the white-clad strangers

Did Templars flee to Scotland and fight under Robert the Bruce at Bannockburn (1314)? Did a fleet slip into Irish or Scottish coves with gold and relics? Did a stern brotherhood, stripped of its banner, reappear as protectors of a king cast out by Rome? The archive is thin; the legend is fat.

Seventeenth- to nineteenth-century local histories and newspapers rehearse a cluster of claims:

Scotland as haven: With Bruce excommunicated and English power menacing, Scotland looked like a place where Rome’s edicts had limited reach.

Bannockburn auxiliaries: Vague references to “white-clad, armoured knights” in Bruce’s retinue invited identification with Templar survivors.

Antrim landings: Ulster traditions place foreign galleys on the North Antrim coast, carrying men and chests ashore.

Gatepost crosses: Antiquarian notes describe a Latinized knightly cross carved into stones or gateposts, later remembered as “Templar marks.”

Temple Church whispers: In London, wardens of the Round Church pointed visitors to suggestive carvings and recited initiation myths that owe more to Victorian taste than to twelfth-century statutes.

A rigorous historian will file these as folklore-valuable evidence for belief, not for fact. A sympathetic reader can do more: see how badly Europe wanted a company of disciplined, mobile, armed outsiders who owed fealty only to one another and to God. If no such corps survived intact, people invented one to bless the victors and to hide treasure in the hills.

XI. Afterlives: from “Palladium” to paperback

The Templar name never lay quiet. Nineteenth-century anti-Masonic fantasy spun a lineage from crusader lodges to a world-conquering “Palladium” that worshipped Lucifer and Baphomet; editors soberly marked the claims as “not proven,” but the story ran. Popular magazines linked cats to heretics and heretics to Templars, delighting in the way language keeps old fears alive. Twentieth-century newspapers recycled the “Baphomet is Mahomet” line alongside sharp skepticism of giant idols and goat gods. The same articles that dismissed idol-worship as invention still granted that the Order could look “non-Christian” to men who wanted it to be.

If there is a thread through these afterlives, it is this: the Templar problem remains a mirror for whichever century is staring at it. To Victorians, the Order became a test case for source criticism; to conspiracy theorists, a hidden hand; to modern culture warriors, a mascot. The medieval brothers-chaste, hungry, sun-burnt, quarrelsome-rarely get a hearing.

XII. A counter-thesis: not Satan, not simple greed-something harder

Let’s try a clean hypothesis that honors what we know without pretending to more:

The Order’s structure and wealth made it politically expendable once its crusading function collapsed. Philip’s policies were opportunistic, but they succeeded because many in Europe were ready to believe the worst.

The accusations bundled stock charges with specific irritants. Stock: sodomy, blasphemy, obscene kisses. Specific: reversed rituals reported (and denied) in confession; vague rumors of a “head”; the whisper “Baphomet.”

Baphomet was usually a misspelling (or deliberate slur) for Mahomet. It sometimes got clothed with imagery-goat of Mendes, severed head-but that dressing belongs to later myth, not to a stable inner Templar theology.

Cultural transfer from the Islamic world through long contact is a likelier seed for talk of “heresy” than diabolism is. A brother saying respectful things about Muslims or using an oath formula heard in Arabic could, through fear and malice, be made to sound like an idolater.

Folklore of dispersal-Bannockburn knights, Antrim hoards-tells us chiefly that Europe wanted the Order to survive somewhere, as conscience or resistance or hope.

None of this canonizes the Templars. It makes them interesting again. It cuts through both the satanic fog and the tidy “jealous king” story to uncover a harder, more human possibility: that the brotherhood’s real “heresy” was competence unconfined by prejudice-learning from enemies, contracting with them, sometimes even admiring them-and that this posture, once named aloud, was intolerable to powers that needed the Crusade to remain a morality play.

XIII. The cat comes back (and why it matters now)

Why carry the “cat theory” with us? Because it shows how an image can become a verdict. If, in German mouths, cat could slide into heretic, then centuries later Templar can slide into symbol-for whatever a movement wants to defend or attack. Modern far-right groups rally behind a fantasy of the Templars as pure border-guards against Islam. The record we’ve traced suggests an ironical corrective: that some of the men they celebrate were exactly the kind of pragmatic intermediaries-deal-makers, language learners, borrowers of science-whom the far right now derides.

Language remembers. A village rumour about a black cat, a scribe’s “Baphomet,” a Paris clerk’s entry about a head-each can still wag the historical dog. We do better when we hold them up to the light, smile, and then ask what real lives might lie underneath.

Coda: What if?

What if the Templars’ most dangerous instinct was curiosity? What if their lodges were not covens but classrooms of the marchlands-where an Iberian brother could learn an Arabic star-name from a Syrian pilot, where a knight who had bargained with an emir for safe passage could say, without shame, that God had given wisdom to more than one people? What if this way of talking-ordinary for men who lived between cultures-sounded, in a Paris court, like profanity?

Strip away the legend and a sober possibility stands: the Templars were suppressed by kings and princes who resented their wealth, yes; but also by a Christian mainstream that could not abide the thought that learning might cross the frontier as easily as caravans did. If so, then the last lesson of the order is not about treasure maps or talismans. It is about how societies punish the translators who make enemies understandable.

That, more than any idol with a carved beard, may be the secret that still makes the Templars feel heretical

Related Articles

8 November 2025

How the Conquering Sun Became the Conquering Galilean26 October 2025

Elmet A Brittonic Kingdom and Enclave Between Rivers and Ridges24 October 2025

The Ebionites: When the Poor Carried the Gospel12 October 2025

Queen of Heaven: From the Catacombs to the Reformation4 October 2025

The Ancient Blood: A History of the Vampire27 September 2025

Epona: The Horse Goddess in Britain and Beyond26 September 2025

Witchcraft is Priestcraft: Jane Wenham and the End of England’s Witches20 September 2025

The Origins of Easter: From Ishtar and Passover to Eggs and the Bunny12 September 2025

Saint Cuthbert: Life, Death & Legacy of Lindisfarne’s Saint7 September 2025

The Search for the Ark of the Covenant: From Egypt to Ethiopia5 September 2025

The Search for Camelot: Legend, Theories, and Evidence1 September 2025

The Hell Hound Legends of Britain25 August 2025

The Lore of the Unicorn - A Definitive Guide23 August 2025

Saint Edmund: King, Martyr, and the Making of a Cult14 August 2025

The Great Serpent of Sea and Lake11 August 2025

The Dog Days of Summer - meanings and origins24 June 2025

The Evolution of Guardian Angels19 June 2025

Dumnonia The Sea Kingdom of the West17 June 2025

The Roman Calendar, Timekeeping in Ancient Rome14 June 2025

Are There Only Male Angels?