Written by David Caldwell ·

The Invisible Threads: A Cultural and Historical Journey Through Ley Lines

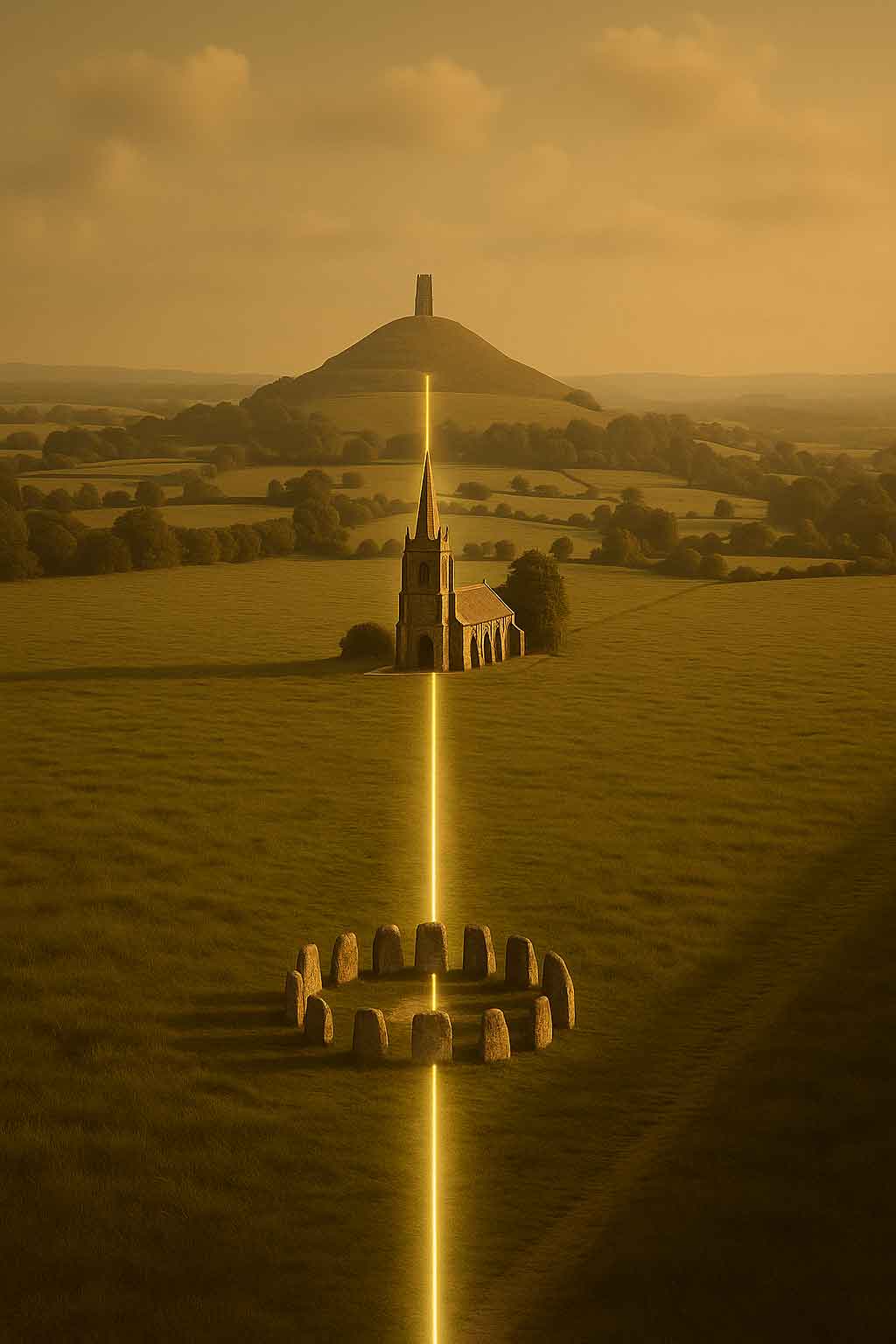

Sacred Landscapes and the Geometry of the Ancients

Sacred landscapes have been buried beneath churches, destroyed by the plough, lost to gravel extraction, or built over by our ever-expanding towns and cities.

What remains are isolated survivors, stone circles, burial mounds, and forgotten markers, perched on hilltops or standing at ancient crossroads. With the larger picture obscured or erased, our pattern-seeking minds take over. We begin to join the dots with lines, tracing imagined or rediscovered alignments across the land.

These lines, often called ley lines, have long captured the imagination. Emerging from the intersection of archaeology, folklore, and mysticism, they offer a tantalising glimpse into the possibility of a lost system of landscape geometry?one that connected sacred sites with precision, purpose, and power.

In 1921, a Herefordshire antiquarian named Alfred Watkins stood atop a hill near Blackwardine and experienced a vision that would redefine the British landscape for generations. He claimed to see a network of ancient straight tracks criss-crossing the countryside, threading through prehistoric mounds, standing stones, old churches, and hilltops. He called them "ley lines" and proposed that they were remnants of a forgotten infrastructure used by ancient peoples to navigate or mark sacred geographies. His book The Old Straight Track became the cornerstone of modern ley line theory, sparking both fervent belief and scientific scepticism.

Pre-Roman Pathways and the Foundations of Alignment

Even before Watkins, Roman engineers observed that their roads often followed existing straight tracks across Britain. These older tracks, sometimes called "green roads" or "corpse roads," were often remarkably direct, linking high places, stone circles, and barrows. In Somerset, for example, many Roman roads run atop these ancient alignments, and in Sussex and Shropshire, researchers have walked the land and verified straight-line connections between Iron Age sites, medieval churches, and even modern buildings. These patterns suggest that Britain once possessed a pre-Roman network of trackways possibly used for spiritual processions, trade, or seasonal migrations.

Some scholars believe the trackways had astronomical or ceremonial importance. David Stanley of Wanstrow described how sites such as Temple Copse, Cole Hill, and Burrow Mump in Somerset seem aligned in a ritual pattern, with beacons or churches marking nodes in an ancient web. A pilgrimage recounted in the 1970s from St Michael's Mount to Glastonbury followed a series of such aligned St Michael churches, suggesting a long-standing connection between ley lines and the veneration of landscape.

The Emergence of Sacred Geometry and the Terrestrial Zodiac

By the mid-20th century, ley line theory evolved beyond Watkins' utilitarian explanation and embraced more mystical dimensions. Writers like John Michell and Anthony Roberts explored the concept of terrestrial zodiacs: vast land-based star maps allegedly marked by natural features and ancient sites. The Glastonbury Zodiac, first proposed in the 1930s and elaborated by a number of esoteric authors, is perhaps the most famous. It overlays the Somerset landscape with immense representations of zodiac signs, said to be outlined by rivers, hedgerows, and paths.

Further north, John Billingsley identified a similar phenomenon in West Yorkshire, which he dubbed the Hebden Bridge Zodiac. He later travelled to Japan to investigate comparable geomantic traditions and discovered that some Japanese researchers had been exploring their own ancient site alignments.

Ley Lines in Japan: A Cross-Cultural Connection

In the early 1990s, Billingsley lived for several months in Osaka, where he connected with Japanese scholars interested in prehistory and sacred geography. He reported the existence of "leyjins", ancient Japanese alignments of temples, shrines, and megalithic sites, that mirrored the British fascination with straight lines and spiritual geography. Some of these lines appeared to connect Shinto shrines and burial mounds, forming geometric patterns reminiscent of British ley theories. Though Japanese archaeology traditionally focused on the past 2,000 years, there was growing interest in earlier sacred landscapes and their possible connections to energy or cosmological design.

Dowsing, Energy, and the Invisible Landscape

While many scientists dismiss ley lines as coincidental or imaginary, some researchers have attempted to measure them using dowsing rods and electromagnetic instruments. Dr. J. Havelock Fidler, an agricultural scientist, used electrostatic field meters to record energy anomalies at standing stones and Roman sites in Sutherland. He claimed that charged stones could be distinguished from uncharged ones and suggested that negative electrostatic fields might explain the sensations reported by dowsers.

David Cowan of Crieff in Scotland went further, mapping a hexagram of energy currents around his hometown. He linked this geometry to Masonic and sacred symbols, identifying alignments between churches, ancient crosses, and hillforts. His work echoed earlier suggestions that ley lines form part of a hidden energetic grid, recognised by ancient builders and preserved in folklore.

From Sacred Paths to Modern Myths

Ley lines have also been associated with darker folklore. A tabloid report once linked the town of Coggeshall in Essex, described as the "murder capital of Britain", to the intersection of two major ley lines. Ghost sightings, poltergeist activity, and even mysterious road gradients like the Electric Brae in Ayrshire have all been ascribed to earth energy fields. Lionel Stanbrook of the Society of Ley Hunters noted that many traditional sightings of headless horsemen and black dogs occur along ancient trackways, often coinciding with corpse roads or burial paths.

Despite the scepticism, ley lines continue to fascinate because they offer an alternative way of reading the landscape. They weave together archaeology, folklore, spirituality, and geography into a holistic framework that transcends modern divisions of knowledge. Whether seen as relics of prehistoric navigation, channels of earth energy, or projections of the human imagination onto the land, ley lines persist as one of the most enduring and mysterious aspects of Britain's sacred geography.

Sources referenced:

- Alfred Watkins, The Old Straight Track

- David Stanley, Somerset Guardian (1974)

- John Michell, View Over Atlantis

- John Billingsley, Hebden Bridge Zodiac research

- Anthony Roberts (ed.), Glastonbury: Ancient Avalon ? New Jerusalem

- David R. Cowan, letters on Crieff hexagram

- Dr. J. Havelock Fidler, Ley Lines: Their Nature and Properties (reviewed by A. C. McKerracher)

- Experience Sussex magazine (2002)

- Assorted local newspaper clippings from Shropshire, Essex, Perthshire, and West Yorkshire

Related Articles

8 November 2025

How the Conquering Sun Became the Conquering Galilean26 October 2025

Elmet A Brittonic Kingdom and Enclave Between Rivers and Ridges24 October 2025

The Ebionites: When the Poor Carried the Gospel12 October 2025

Queen of Heaven: From the Catacombs to the Reformation4 October 2025

The Ancient Blood: A History of the Vampire27 September 2025

Epona: The Horse Goddess in Britain and Beyond26 September 2025

Witchcraft is Priestcraft: Jane Wenham and the End of England’s Witches20 September 2025

The Origins of Easter: From Ishtar and Passover to Eggs and the Bunny12 September 2025

Saint Cuthbert: Life, Death & Legacy of Lindisfarne’s Saint7 September 2025

The Search for the Ark of the Covenant: From Egypt to Ethiopia5 September 2025

The Search for Camelot: Legend, Theories, and Evidence1 September 2025

The Hell Hound Legends of Britain25 August 2025

The Lore of the Unicorn - A Definitive Guide23 August 2025

Saint Edmund: King, Martyr, and the Making of a Cult14 August 2025

The Great Serpent of Sea and Lake11 August 2025

The Dog Days of Summer - meanings and origins24 June 2025

The Evolution of Guardian Angels19 June 2025

Dumnonia The Sea Kingdom of the West17 June 2025

The Roman Calendar, Timekeeping in Ancient Rome14 June 2025

Are There Only Male Angels?