Written by David Caldwell ·

The Lore of the Unicorn - A Definitive Guide

Ancient Descriptions and Early Reports

Greek and Roman authors describe a one-horned beast native to India. Ctesias (c. 400 BC) speaks of a wild ass with a single horn.

Aristotle mentions an "Indian ass" among the few solid-hoofed animals that may have a single horn.

Pliny the Elder adds vivid detail: the monoceros has "the body of a horse, the head of a deer, the feet of an elephant, and the tail of a lion," with one horn on the forehead. In some accounts it is exceptionally swift.

A later summary lists colours ascribed to the creature: body white, head red, eyes blue, and a horn whose base is white,

?middle black, and tip red.

These classical portraits may derive from real animals: the Indian rhinoceros and the oryx. Observers note that the oryx can look one horned in profile; males sometimes break one horn in combat, leaving a single remaining horn.

An African anecdote explains how such sightings fuelled the legend: hunters describe long, straight antelope horns prized as trophies; from afar, an antelope with one broken horn appears truly one horned. This "single horn" could then be carried ceremonially like a sceptre, and stories accreted around it.

The Biblical 'Unicorn' and the Aurochs

The Hebrew Re?em entered Greek as monokeros ("one horned") and into Latin and English Bibles as "unicorn."

Later writers stressed that Re?e better fits a two horned wild ox, the aurochs (urus). Boethius describes white bulls?with crisp curling manes, fierce and untameable - creatures captured only by crafty labour and said to die of "insupportable?dolour" once taken. The aurochs likely survived in parts of Europe into the fifteenth century.

How the Medieval Unicorn Took Shape

Crusader era artists and "monkish" copyists refined crude earlier sketches into the familiar heraldic form. Travellers brought?home exotic horns - chiefly narwhal tusks - displayed as unicorn relics. A "fine" example could be seen at St. Denis; others appeared across Europe.

Seventeenth century writers recorded what they took to be unicorn horns. Thomas Fuller writes of horns "plain" (such as one?in St. Mark's, Venice) and others "wreathed"-"wrinkles of most vivacious unicorns," he speculated - with colour turning from white when new to yellow with age (like one formerly in the Tower).

One Victorian essay calls the narwhal the "sea unicorn," explicitly tying carved "unicorn horns" to that marine mammal.

Medieval bestiaries gave the unicorn moral character: fierce and uncatchable, yet irresistibly drawn to a maiden. Seated alone in the forest, the maiden lures the beast; it lays its head on her lap and sleeps, whereupon hunters seize it. Shakespeare nods?to another capture tale: "Unicorns may be betray?d with trees," the beast impaling its horn in a trunk during a charge.

The horn was credited with astonishing virtues: cups made from it would 'sweat' in the presence of poison; water stirred with?the horn was purified; powdered horn was a remedy for epilepsy, plague, hydrophobia, drunkenness, and even tooth whitening.

Some bestiaries picture the unicorn leaping at an elephant and driving its horn into the throat - an emblem of purity conquering?brute strength.

The Lion and the Unicorn

A persistent legend makes the lion the unicorn?s arch foe. An early modern naturalist (Topsell, quoted in a clipping) claims?the lion hides behind a tree; the charging unicorn pins its horn in the trunk; the lion then kills it "without all danger."

The later nursery rhyme - "The lion and the unicorn were fighting for the crown" - echoes the heraldic pairing that would come to?symbolise England (lion) and Scotland (unicorn).

Heraldry, Coins, and National Identity

The unicorn appears in Scottish heraldry long before union with England. Gold coins from the reign of James III (1486?1487) show a unicorn sejant or couchant supporting a shield.

Sir David Lindsay of the Mount, Lord Lyon King of Arms under James V, records the unicorn in the heraldic tradition and repeats?the maiden capture legend.

Hector Boece even asserted that unicorns were seen in the forests of Scotland.

As a supporter of the Royal Arms of Scotland, the unicorn was well established when James VI of Scotland acceded to the English throne in 1603. The unified Royal Arms paired the English lion with the Scottish unicorn - "facing the English lion" - to?signify union of the two kingdoms.

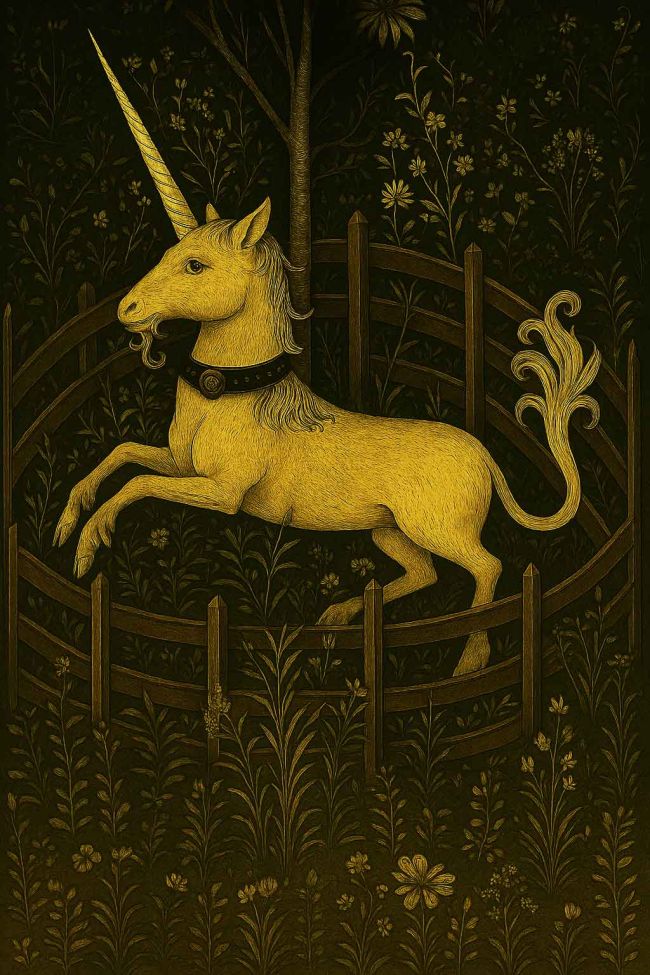

In heraldry the unicorn is commonly shown **chained**: a sign of ferocious, untameable power brought into the service of lawful authority - "chained, yet untamed."

The unicorn became a widely used inn sign. One clipping dates its popularity to 1604, on the accession of James I.?Some inn signs showing a unicorn with its head on a maiden?s lap may even pre date the political union.

The Unicorn in Art - The Hunt and the Garden

A set of great tapestries - described in detail - presents the unicorn cycle: the beast at a fountain (whose waters it can purify),?brought to bay by hounds; captured (a missing panel likely showed the maiden with the unicorn in her lap); carried home on a?horse; and finally resurrected within a fenced garden or park, alive and vigorous forever.

The "mythical chase" was especially popular in German art of the fifteenth and sixteenth centuries. In Christian symbolism?the unicorn stands for the Incarnation: the Son of God, as unicorn, seeks refuge with the Virgin.

The famous French set at the Mus?e de Cluny - rich reds, lions, hounds, hunters, musicians, and ladies - became emblematic of the subject. Municipal purchase in 1852 preserved them for public display.

Tudor - Stuart and Later Lore

Popular accounts stress that "unicorns" were catalogued in natural histories as late as the seventeenth century.?

Writers conflated exotic quadrupeds and trophies; crusader tales and heraldic needs fixed the now familiar form -?a spirited, horse like creature with a long, spiral horn, sometimes shown with the tail of an ass, a goatish beard, and hind legs like an antelope.

The unicorn?s supposed gentleness "at mating time" was thought to explain the virgin lure motif. Cups engraved with unicorns symbolised the horn?s power against poison.

Eastern Parallels - Tibet and Nepal

Multiple sources claim that a one horned animal exists in Tibet. Local names include: Thibetan serou; Mongol keer; Chinese too ki seou ("one horned animal") and ki touou ("straight horn"); Manchu bokoo; Sanskrit khadga. Mongols?sometimes conflated it with the rhinoceros, but other accounts clearly describe an antelope like creature.

Serou Dzong, means "the village of the land of unicorns," in Kham (eastern Tibet).

A manuscript examined by Major Latter mentions the one horned too po and records a horn: ~50 cm long, ~12 cm in circumference at the base, black, smooth, knife like, and almost straight.

Resident naturalist B. H. Hodgson identified the animal with a high mountain antelope (also referred to as Antelope Hodgsonii). Descriptions emphasise elegance; upper body white, darker below; exceptionally soft, insulating hair; long pointed black horn with small undulations; herds frequent high valleys and riverbanks; the animals are shy, swift, and courageous when pressed.

A Mongol chronicle tells how, as Timur ascended Mount Djindjipala, a one horned serou approached three times as though in?homage - used as rhetorical flourish to show the monarch?s destined success.

From Africa comes another naturalistic basis: the oryx. Observers note that males break horns in battle; from a distance an oryx with a missing horn looks like a true one horned beast.

Narwhals and 'Unicorn Horns'

Numerous trophies long displayed as unicorn horns were actually narwhal tusks - "sea unicorn" relics carved and mounted.

?A notable specimen was kept at St. Denis; others were shown in European treasuries. Fuller and later writers comment on?horns plain and spiral, white when fresh and yellow with age.

The practice fed the trade in "unicorn cups" and the belief that such material neutralised poison and purified food and drink.

The Lion & Crown - Politics and Rhyme

The heraldic pairing of lion and unicorn - England and Scotland - filters into popular memory in the nursery rhyme:

"The lion and the unicorn were fighting for the crown?"

Earlier prose keeps the predatory dynamic: the lion exploits the unicorn?s charge to trap the horn in a tree and kill it.

A Modern 'Unicorn'

In 1936 Dr. Franklin Dove (Maine University) surgically transplanted the horn buds of a day old calf so that they grew?together into a single central horn - a living "unicorn." He proposed that similar procedures by earlier peoples could have?helped seed or sustain the legends, and even speculated on how such a practice might symbolically strengthen a bull in combat, an echo of the age old lion and unicorn contest for the crown.

Meanings and Emblems

Beyond bestiaries, the unicorn becomes an emblem of chastity and is associated with the Virgin Mary in medieval art (the Annunciation depicted with an angel and a unicorn). In Christian readings the unicorn also symbolises Christ himself, passing into art as a sign of purity and sacrifice.

As a national symbol of Scotland, the chained unicorn on the Royal Arms remains a potent device: fierce power harnessed, independence with loyalty -"chained, yet untamed."

The unicorn may be the animal "that never was," yet in lore, symbol, art, and armorial splendour, it remains triumphantly, indelibly real.

Related Articles

8 November 2025

How the Conquering Sun Became the Conquering Galilean26 October 2025

Elmet A Brittonic Kingdom and Enclave Between Rivers and Ridges24 October 2025

The Ebionites: When the Poor Carried the Gospel12 October 2025

Queen of Heaven: From the Catacombs to the Reformation4 October 2025

The Ancient Blood: A History of the Vampire27 September 2025

Epona: The Horse Goddess in Britain and Beyond26 September 2025

Witchcraft is Priestcraft: Jane Wenham and the End of England’s Witches20 September 2025

The Origins of Easter: From Ishtar and Passover to Eggs and the Bunny12 September 2025

Saint Cuthbert: Life, Death & Legacy of Lindisfarne’s Saint7 September 2025

The Search for the Ark of the Covenant: From Egypt to Ethiopia5 September 2025

The Search for Camelot: Legend, Theories, and Evidence1 September 2025

The Hell Hound Legends of Britain23 August 2025

Saint Edmund: King, Martyr, and the Making of a Cult14 August 2025

The Great Serpent of Sea and Lake11 August 2025

The Dog Days of Summer - meanings and origins24 June 2025

The Evolution of Guardian Angels19 June 2025

Dumnonia The Sea Kingdom of the West17 June 2025

The Roman Calendar, Timekeeping in Ancient Rome14 June 2025

Are There Only Male Angels?