Written by David Caldwell ·

Saint Edmund: King, Martyr, and the Making of a Cult

I. The Christianisation of East Anglia

When we trace the story of Saint Edmund, we must first step back to the early 7th century, when Christianity was still young in the eastern kingdoms of England. East Anglia, with its royal centre at Rendlesham and its fortress towns along the Suffolk coast, was gradually drawn into the Christian orbit through the efforts of two remarkable missionary saints.

St Felix of Burgundy arrived around 630, invited by King Sigebert, himself newly converted. Felix established his bishopric at Dunwich, then a thriving port and now lost beneath the waves. There he built churches, founded schools, and taught the Psalms - the foundations of Christian kingship and learning. Bede praised him as the ?apostle of East Anglia,? who turned an entire people from darkness to faith.

A few years later came St Fursa, an Irish monk and mystic, who founded a monastery at Burgh Castle near Yarmouth. Fursa was famed for visions of angels and devils that shaped medieval ideas of the afterlife. He too had the support of King Sigebert, who would later retire as a monk himself.

Thus, by the mid-7th century, East Anglia was a Christian kingdom, with churches, schools, and monasteries. Yet it was also vulnerable - caught between Mercia, Wessex, and Northumbria, and, by the late 8th century, the increasing menace of the Vikings.

II. The Life and Martyrdom of Edmund

Origins and Accession

Edmund?s beginnings are shrouded in mystery. Some accounts describe him as a descendant of the old Anglo-Saxon royal line of East Anglia; others claim he was the son of Alkmund of Saxony, brought over the sea to inherit. According to Catholic biographers recorded by later writers, he was ?a German prince, sent in Saxon times to help his countrymen in England.?

What seems likely is that he was born c. 841?842, and brought to England as a youth. In 855 or 856, he was crowned at Bures St Mary, Suffolk, in a ceremony led by Bishop Humbert of Elmham. A boy-king of only 14, he first spent a year in religious retreat, committing the Psalms to memory before assuming full rule. His piety, justice, and simplicity of life made him beloved of his subjects.

The Viking Advance

The Great Heathen Army, a vast coalition of Viking forces, landed in 865 and cut a bloody swathe through England. Northumbria was crushed, Mercia humbled. By 869/870 they returned to East Anglia, demanding submission.

Some sources name Ingvar (Ivar the Boneless) as leader, others mention a Danish king called ?Lothparch,? described by tradition as a kinsman of Edmund. It was said that Lothparch was slain in Denmark by Edmund?s own falconer, who, having landed there earlier, laid the blame for hostilities on his royal master and struck down the Danish king.

When the Danes came to Thetford they were led by Ingvar and Hubba, who sent messengers to Edmund at Hoxne. The terms they offered were stark: peace could only be secured by the surrender of half the kingdom?s treasure and the subservience of Edmund and his people to the Danes.

Edmund refused such a one-sided bargain. A fierce battle was fought at Snarehill, near Thetford. Saxon accounts claimed it ended indecisively: the English may have had the better but suffered fearful losses, unable to press their advantage. In the aftermath, Edmund withdrew to Hegelisdun (Hoxne), one of his favoured residences, surrounded by forest and with a church nearby.

Betrayal and Arrest

At Hegelisdun, Edmund entered the church ?to show himself a member of Christ.? With him was Bishop Humbert of Elmham. Surrounded by Danes and pressed to submit, Edmund again refused, declaring that he would not save his kingdom by betraying Christ. He was dragged from the altar with Humbert at his side.

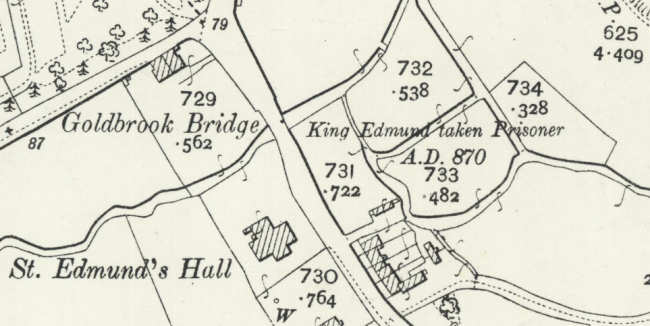

Some accounts say Edmund hid under Gold Brook Bridge and a newly married couple betrayed his hiding place to the Danes, a treachery later remembered in local superstition: bridal couples who crossed Goldbrook Bridge at Hoxne were thought to bring doom upon themselves.

The Passion of Edmund

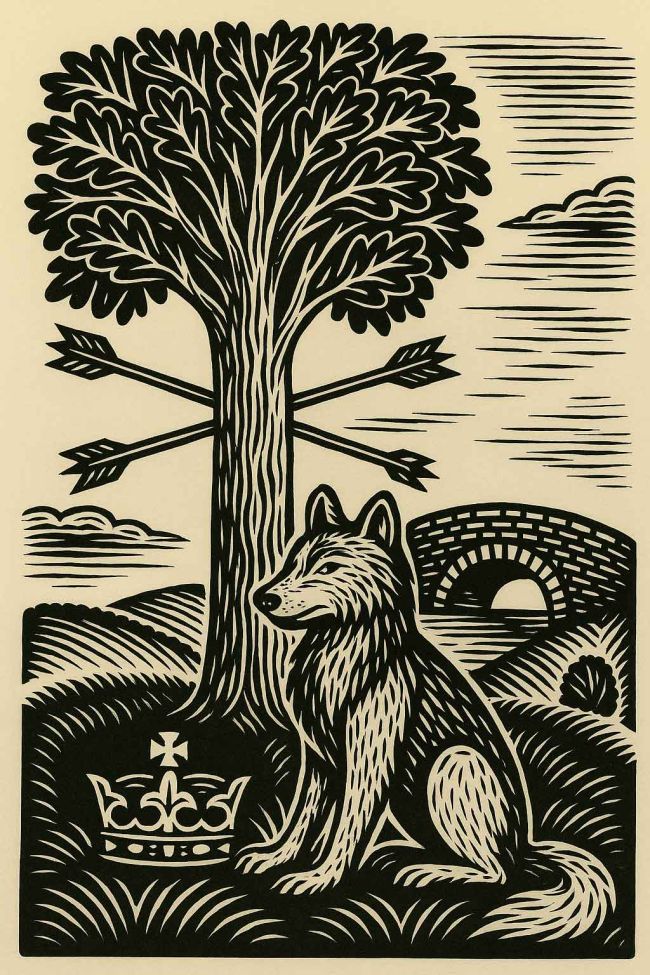

Edmund was struck in the face by his tormentors; when his head was later found, several of his teeth were missing. He was bound to a tree, scourged, and mocked. Then he was set up as a target for the archers, their grey goose shafts piercing him until ?he resembled a thistle covered with prickles, or a hedgehog bristling with spines.?

Yet still he lived. His executioners deliberately spared the vital parts. At last, they beheaded him, and Bishop Humbert met the same fate. Their bodies were thrown into the depths of the forest or hidden by friends - accounts differ.

The Cry of the Head

The date was 20 November 870. Edmund was not yet 29 years old, and had reigned for 15. Forty days later, his followers sought the body. They found it lying in the open field, uncorrupted, but the head was missing.

Only when they entered the forest did they hear a voice crying, ?Here! Here! Here!? They followed the sound and discovered the head guarded by a wolf. The beast yielded it willingly. The head was reunited with the body, the seam miraculously healed so that the two grew together, leaving only a red line as proof of the martyrdom.

The grateful people, remembering the loyalty of the beast, preserved its remains as well. At Bury, a small casket was said to contain the bones of the very wolf that had guarded Edmund?s head. In this curious relic, piety and folklore were entwined: the faithfulness of the animal seen as part of divine providence.

The Wolves and the Sacred Oak

Local tradition wove yet another strand into the memory of St. Edmund?s Oak. It was said that when wolves still roamed the forests of Suffolk, an aged or wounded beast would make its final journey to the tree. Beneath the shadow of the sacred oak.

Reproduced with kind permission of the National Library of Scotland https://maps.nls.uk/

Incorruption and Translations

For years, the saint?s relics were kept at Hoxne. Later they were translated to Beodricesworth (Bury St Edmund?s). When the coffin was opened a century later, the body was found to be whole and incorrupt. The head had knit again to the trunk, and the saint?s features were unchanged.

In 1010, during another Danish invasion, Edmund?s relics were carried to London for safekeeping. For a time, he was regarded as patron saint of the city, and miracles were reported at his shrine there. Later, the relics were returned to Bury, where the cult flourished until the Reformation.

The shrine at Bury grew to be one of the greatest in medieval Europe, famed for the number and splendour of its miracles. The Cluniac monks of Thetford treasured coffins and relics associated with the saint, ensuring his veneration continued through the Middle Ages.

III. From Grave to Shrine: The Making of a Cult

First Burial at Hoxne

For thirty-three years, Edmund?s body lay at Hoxne, close to the place of his martyrdom. A humble wooden chapel sheltered the grave, and traditions grew rapidly around it.

The bridge across Goldbrook carried a dark reputation. Tradition held that Edmund was betrayed by a newly married couple who revealed his hiding place to the Danes. As punishment, local superstition warned that any bridal pair who crossed the bridge on their wedding day would be cursed. The brook itself was said to have swallowed the golden bracelet the king wore when bound to the tree - giving the place its name, Goldbrook.?Another account said that it was the sun glinting off his gold spurs which revealed his hiding place.

On the old reading room now a village hall is a carving depicting the King hiding under the bridge while a wedding party crosses above.

The oak to which Edmund had been tied became a relic in its own right. Crosses and beads were fashioned from its wood. When the tree finally collapsed in 1848, workmen discovered within its trunk a skeleton and an arrowhead, a startling confirmation, so it was claimed, of the ancient story. Portions of the oak were preserved: Sir Edward Kerrison and Lady Bateman both held fragments; Hoxne church displayed relics; and the English Benedictines at Downside Abbey treasured a piece bearing the inscription: ?St. Edmund?s Oak, Hoxne, Suffolk.? A chair made from the oak was kept at Hoxne, a solemn memorial to the martyr.

At the foot of the hill, where the road crosses the Goldbrook, stood St. Edmund?s Hall, an inn closely tied to the tradition. Its sign showed a wolf holding a crown in its mouth - a direct reference to the beast that guarded the king?s severed head.

Abbey Farm and Hoxne Abbey

Nearby, in Cross Street, was Abbey Farm, the first tangible reminder of the ancient cult. The chapel built over Edmund?s tomb had belonged to the Benedictines of Norwich, who rebuilt it as the cell or chapel of St. Edmund, King and Martyr. It was dependent on the Benedictine priory at Norwich, later leased to Sibton Abbey, and eventually passed into the hands of successive bishops.

By Clarke?s time, only partial ruins remained: fragments of wall and grass-covered mounds marked the spot of the old chapel. The farmhouse bore a later front, but behind it stood striking Elizabethan features - lofty clustered chimney stacks and a great porch fifteen feet high, built with alternating vertical lines and brick courses. Above the porch door hung a huge pair of antlers, probably of the red deer.

Most curious of all was a doorway flanked by four bizarre painted figures, life-sized, about six feet tall. Though faded, their colours hinted at former brilliance. One held a sickle, another a posy of flowers. A male figure appeared in shirt, hose, and hat, while another, moustached and crowned, dressed as a knight, seemed to measure his stature against his sword. Local lore claimed this last figure represented Edmund himself; antiquaries speculated the group might depict Ceres and Flora, alongside Hercules and the sainted king - a strange mingling of Christian and pagan imagery.

Carvings of Falconer, Eagle, and Stag

Inside the porch was a holy-water stoup. Above the inner doorway was a carving of a falconer, with hawk perched on his wrist and a hound at his side - a vivid glimpse into medieval life and symbolism.

Another doorway, later leading into a dairy, carried the carving of a spread-winged eagle, measuring three feet from tip to tip. Over the staircase turret window, a finely executed stag, its head turned backward, looked out across the yard.

These carvings, along with the porch figures, made Abbey Farm one of the most remarkable survivals of East Anglian popular devotion. Here, folk memory of Edmund was mingled with rural art, hunting motifs, and even pagan echoes, rooting the Christian martyr within the deeper layers of Suffolk tradition.

IV. The Translation to Bury and the Growth of the Shrine

Removal from Hoxne to Bury

In time, the body was removed from Hoxne to Beodricesworth - the town that would soon be known as Bury St. Edmund?s. The translation was overseen by Bishop Theodred. Once installed at Bury, Edmund?s incorrupt relics became the focus of one of the greatest shrines in medieval England.

Miracles multiplied. Pilgrims of every class - peasants, merchants, nobles, and kings - flocked to his tomb. Gifts of treasure and land poured in. Bury Abbey grew into one of the wealthiest and most influential monasteries in the kingdom. It became a place where politics and piety intertwined: councils were held, charters confirmed, and oaths sworn before the martyr king?s shrine.

Though the shrine was destroyed at the Reformation and the abbey left in ruins, the fame of Edmund endured, and the ruins of Bury still recall the devotion that once made it the spiritual heart of East Anglia.

The Church on the Hill at Hoxne

Though Bury rose to prominence, Hoxne itself never forgot. Climbing the hill from Goldbrook Bridge, one comes to Hoxne Church, dedicated to Saints Peter and Paul. Its tower and spire dominate the countryside, a constant reminder of the saint.

The church is rich with antiquities. On the south porch are three carved niches, and the tower staircases are roofed with groined vaulting. Inside, on the north wall of the nave, a finely-carved stone bracket for an image still survives. The chancel preserves a piscina and sedilia, evidence of its medieval liturgy.

In the vestry lies a treasure: an ancient cope of purple silk, embroidered with gold thread, said to have belonged to Bishop Walter Lyhart, who ruled Norwich from 1446 to 1472. It was in his episcopate that the splendid rood loft and screen - still extant - were probably erected.

Elsewhere, the chancel contains a second piscina with double drain, and at the east end of the north aisle, an aumbry. A tablet records benefactions from Edward VI and Elizabeth. A brass commemorates William Gay, rector, who died in 1614.

Memorials also honour the Knyvett family of Ashwellthorpe and the Maynards of Little Fransham, linking the church to Norfolk?s landed gentry.

In the churchyard lies the tomb of Thomas Maynard, who died in 1742, inscribed with a verse both solemn and affectionate:

Here lies a man both wise and great,

Whose life was free from pride or state;

He feared God, and loved the poor,

And died beloved by rich and poor.

V. The Saint?s Memory and Legacy

So much, then, for the associations of St. Edmund with Hoxne, the quiet Suffolk village where the last scene of his life is believed to have taken place. There, amid the peaceful countryside, linger traditions of the martyr king. The bridge, the oak, the inn sign, the relics in the church, and Abbey Farm - all keep alive the memory of East Anglia?s patron saint.

His death and burial gave England a shrine which in later centuries ranked among the greatest in Christendom. At Bury St. Edmund?s, his relics drew pilgrims in uncounted numbers, from humble peasants to the highest nobility. Wealth and honour poured in, and the abbey became a place where not only devotion but also politics and power gathered. Oaths of allegiance were sworn before his shrine; his cult helped shape the very identity of East Anglia within England.

Even after the Reformation stripped the shrine and shattered the abbey, the name of Edmund endured. His story continued to be told in sermons, in ballads, and in the living traditions of Suffolk and Norfolk villages. His steadfastness - refusing to deny Christ even when offered life and dominion - remained a model of Christian kingship and sacrifice.

Today, the ruins of Bury speak of the wealth and splendour that once surrounded his cult, while at Hoxne, the landscape itself preserves his memory: the Goldbrook where his bracelet was lost, the bridge of betrayal, the inn sign with the wolf and crown, the site of the martyr?s oak, the bizarre painted figures at Abbey Farm, and the carvings of falconer, eagle, and stag. Hoxne Church, with its cope, piscinae, brasses, and epitaphs, stands as a lasting witness to centuries of devotion.

In East Anglia, his name is enshrined not only in stone and parchment but in the very traditions of the countryside. His patient endurance, his fidelity to his faith, and his tragic death made him one of the outstanding figures of Saxon England. More than eleven centuries later, his memory remains inseparably linked with the land where he fell - a martyr, a king, and the patron saint of East Anglia.

The Hoved?ya Mystery

In 1147, Cistercian monks from Kirkstead in Lincolnshire sailed across the North Sea to establish a new monastery on the island of Hoved?ya, near Oslo. They did not find a wilderness but a site already hallowed: a chapel was standing there, and it bore a dedication not to a local saint, but to St Edmund of East Anglia. Rather than replace it, the monks incorporated the chapel into their new abbey.

How Edmund?s name had reached Norway so early remains unexplained. His cult was widespread in England, yet the choice of a remote Norwegian island for such a dedication suggests more than mere chance. Trade, seafaring, and kinship bound East Anglia and Scandinavia closely together in the ninth and tenth centuries. Some have even speculated that Edmund himself may have had Norse blood, a link that would help explain why Norwegians cherished his memory.

The dedication at Hoved?ya, centuries before St Edmund?s cult became a pan-European phenomenon, hints at old ties across the North Sea- ties of faith, kinship, and memory whose full story is now lost to history. The chapel remains as a tantalising clue, leaving us to ponder why a Saxon king-martyr was remembered on the fjord outside Oslo.

Location

Related Articles

8 November 2025

How the Conquering Sun Became the Conquering Galilean26 October 2025

Elmet A Brittonic Kingdom and Enclave Between Rivers and Ridges24 October 2025

The Ebionites: When the Poor Carried the Gospel12 October 2025

Queen of Heaven: From the Catacombs to the Reformation4 October 2025

The Ancient Blood: A History of the Vampire27 September 2025

Epona: The Horse Goddess in Britain and Beyond26 September 2025

Witchcraft is Priestcraft: Jane Wenham and the End of England’s Witches20 September 2025

The Origins of Easter: From Ishtar and Passover to Eggs and the Bunny12 September 2025

Saint Cuthbert: Life, Death & Legacy of Lindisfarne’s Saint7 September 2025

The Search for the Ark of the Covenant: From Egypt to Ethiopia5 September 2025

The Search for Camelot: Legend, Theories, and Evidence1 September 2025

The Hell Hound Legends of Britain25 August 2025

The Lore of the Unicorn - A Definitive Guide14 August 2025

The Great Serpent of Sea and Lake11 August 2025

The Dog Days of Summer - meanings and origins24 June 2025

The Evolution of Guardian Angels19 June 2025

Dumnonia The Sea Kingdom of the West17 June 2025

The Roman Calendar, Timekeeping in Ancient Rome14 June 2025

Are There Only Male Angels?