Written by David Caldwell ·

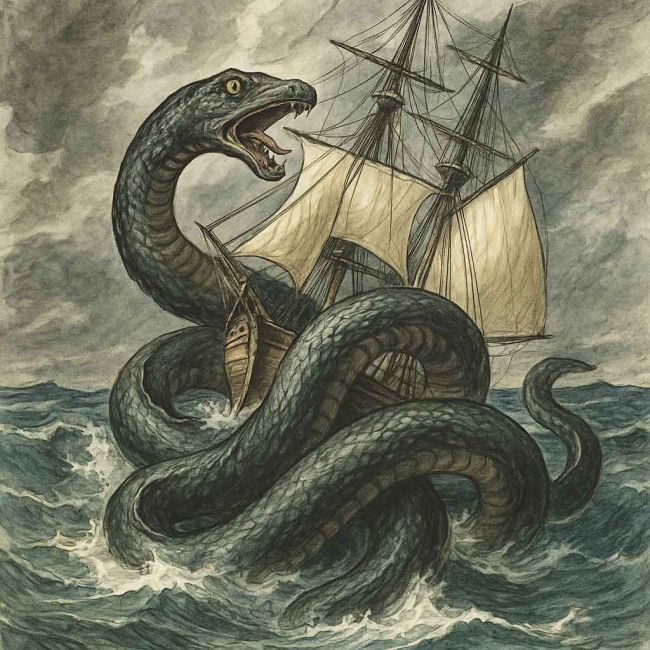

The Great Serpent of Sea and Lake

From Myth to Natural History and the Unknown Depths

Origins in Myth and Scripture

The sea serpent is as old as human storytelling. The Bible offers early visions of such beings, the ?great fish? that swallows Jonah whole, Leviathan in the Book of Job, and Dagon, the half-man, half-fish deity whose temple stood in Ashdod. Milton, in Paradise Lost, described Dagon as:

?Sea monster, upward man

And downward fish: yet had his temple high

Rear?d in Azotus, dreaded through the coast

Of Palestine??

In classical tradition, Scylla and Charybdis guarded perilous straits, while in Norse mythology, the Midgard Serpent J?rmungandr encircled the world beneath the waves, destined to rise at Ragnar?k to battle the gods. Even the English nickname ?Old Nick,? later a term for the Devil, has Norse roots and is sometimes linked to monstrous sea creatures.

British folklore also tells of the Great Orm, a vast serpent or sea dragon remembered in place-names like the Great Orme headland in North Wales. To earlier generations, the ocean was the last wilderness, a place of divine punishment, monstrous predators, and supernatural forces.

Early Sightings and Folklore of Lakes and ?Great Worms?

Belief in monstrous serpents extended to inland waters. The Echo (London) in 1871 recorded tales of vast lake-dwelling ?worms,? including the Great Orm. In Scotland, lochs were said to hide giant eels or dragons, and in 1871 reports from Loch Fell near Oban told of a colossal serpent-like form, 300 feet long, partially embedded in the shore with faintly visible feet, whether fossil, idol, or curiosity, it recalled the ?Great Worms? of English and Welsh legend.

Newspaper archives from the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries add further detail. The Hereford Journal (1786) described a monstrous fish stranded by the tide, its length compared to a ship?s mast. The Gazette of the United States (1793) told of a giant serpent pursuing a vessel off New England, its head lifting clear of the waves. In 1807, The Scots Magazine reported northern fishermen seeing cable-like bodies rising and sinking in long arcs.

The Pauline Incident

One of the most dramatic maritime encounters came from the British barque Pauline. In 1875, Captain Drevar reported his crew saw a sperm whale locked in combat with a gigantic serpent. One coil looped twice around the whale?s body, another encircled its neck, while the creature?s head and shoulders reared high above the water. The sea frothed red before the whale was dragged under.

A decade later, Mr. Hoyle of the Challenger Commission retold the story, noting that some believed the attacker could have been a colossal squid. Others suggested misinterpretations, porpoises swimming in line, seaweed masses, or distant hills, yet Hoyle admitted some cases defied easy explanation. The Pauline?s log, with multiple witnesses, remains one of the most vivid sea-serpent accounts.

Victorian ?Monsters on Tour?

By the late Victorian and Edwardian eras, fascination with sea monsters moved from ship decks to exhibition halls. Travelling shows displayed ?wonderful sea monsters? in tanks or on platforms, sometimes genuine large fish or whales, other times taxidermy composites stitched from multiple animals.

Showmen linked their exhibits to famous reports, proclaiming their specimens to be ?the very monster described by the captain of the Pauline.? For many landlocked Victorians, these were their first close-up encounters with ocean giants. Even when naturalists identified them as basking sharks, giant sturgeon, or clever hoaxes, the spectacle kept the legends alive.

From Myth to Natural History

Nineteenth-century naturalists sought to explain old accounts. Olaus Magnus?s ?six-legged serpent? was later recognised as a basking shark; other ?serpents? turned out to be whales or porpoises swimming in sequence. The discovery of the giant squid, a known foe of sperm whales, lent some credence to stories like the Pauline incident.

Some scientists speculated that rare deep-sea creatures might be driven to the surface by undersea earthquakes, volcanic eruptions, or sudden seabed shifts. Mariners in the Pacific reported strange serpentine shapes after submarine eruptions, alongside floating pumice and discoloured seas.

Science Advances, Mystery Endures

By the twentieth century, taxonomy and oceanography had identified many former ?monsters? as oarfish, sharks, or whales. The oarfish, reaching over 30 feet, likely inspired serpent legends across cultures. We now have deep-sea footage of giant squid and can recognise whale behaviours once mistaken for attacks.

Yet the ocean remains largely unexplored, more of Mars has been mapped than Earth?s seabed. In its deepest trenches, life forms endure pressures unimaginable at the surface, and some may still rival the size and strangeness of the beasts of legend.

In the end, the boundary between myth and science is a meeting place, not a dividing line. From J?rmungandr to the Great Orm, from Loch Fell?s mysterious form to the coils glimpsed from the Pauline, the sea serpent endures as both a symbol of the unknown and a tantalising possibility, a reminder that the ocean still holds its secrets, waiting for the next great discovery.

Related Articles

8 November 2025

How the Conquering Sun Became the Conquering Galilean26 October 2025

Elmet A Brittonic Kingdom and Enclave Between Rivers and Ridges24 October 2025

The Ebionites: When the Poor Carried the Gospel12 October 2025

Queen of Heaven: From the Catacombs to the Reformation4 October 2025

The Ancient Blood: A History of the Vampire27 September 2025

Epona: The Horse Goddess in Britain and Beyond26 September 2025

Witchcraft is Priestcraft: Jane Wenham and the End of England’s Witches20 September 2025

The Origins of Easter: From Ishtar and Passover to Eggs and the Bunny12 September 2025

Saint Cuthbert: Life, Death & Legacy of Lindisfarne’s Saint7 September 2025

The Search for the Ark of the Covenant: From Egypt to Ethiopia5 September 2025

The Search for Camelot: Legend, Theories, and Evidence1 September 2025

The Hell Hound Legends of Britain25 August 2025

The Lore of the Unicorn - A Definitive Guide23 August 2025

Saint Edmund: King, Martyr, and the Making of a Cult11 August 2025

The Dog Days of Summer - meanings and origins24 June 2025

The Evolution of Guardian Angels19 June 2025

Dumnonia The Sea Kingdom of the West17 June 2025

The Roman Calendar, Timekeeping in Ancient Rome14 June 2025

Are There Only Male Angels?