Written by David Caldwell ·

Unearthing the Boundary with Dumnonia: Britain's Last Stand

Introduction

In the twilight of Roman Britain and the dawn of the Anglo-Saxon era, the West Country stood apart. While the eastern regions of Britannia yielded to Germanic rule, the rugged hills, river valleys, and coastal trade ports of the southwest harboured a tenacious, post-Roman kingdom: Dumnonia. Centered on Cornwall and Devon, but with influence stretching into modern Somerset and Dorset, Dumnonia retained its Celtic identity long after Rome?s legions had departed. This article traces archaeological finds, place-names, landscape analysis, and early historical sources to argue for a broader, more defensible eastern frontier of Dumnonia, a last redoubt of British resistance.

To read more about the Kingdom of Dumnonia Click Here

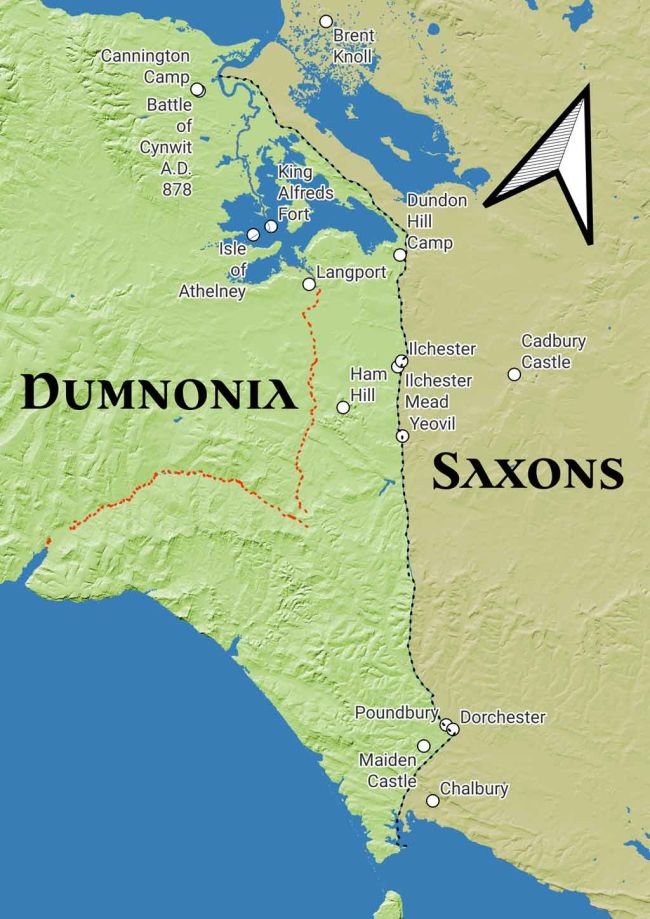

The Map: Reconstructing the Ancient Landscape

The map included in this article reconstructs the possible eastern frontier of Dumnonia using modern topography and archaeological evidence. A Digital Elevation Model (DEM) was employed to highlight the ancient wetlands that once defined the landscape, particularly the Somerset Levels. These wetlands, now drained, would have formed a formidable inland sea stretching from Brent Knoll to Langport and southward toward the Poldens. In this map:

- Blue areas show the ancient waterways and lowlands that would have been tidal or seasonally flooded.

- Dashed red lines suggest a plausible hard frontier following the rivers Axe and Parrett.

- Black dashed lines trace the proposed boundary formed by Roman roads running from Portland to Dorchester and Ilchester to Polden Hills and beyond.

- White dots mark key hillforts, Roman towns, and sites of strategic importance.

This visual representation argues for a practical boundary based on terrain: a defensible frontier backed by marshland and anchored by forts such as Ham Hill, Cadbury Castle, and Maiden Castle. The western side of the line would be Dumnonia; the east, Saxon Wessex.

The Natural Border: Rivers and Marshes

The Parrett and Axe rivers likely defined the natural extent of Dumnonia to the northeast. These rivers, combined with the inland sea formed by the Somerset Levels, created a natural defensive line against encroaching Saxon settlers. In the early medieval period, the levels were likely impassable in winter and treacherous year-round without local knowledge. This landscape isolated key British strongholds such as Glastonbury Lake Village, Brent Knoll, and Langport.

The Role of Roman Infrastructure

The eastern boundary shown in the map closely follows the line of Roman roads from Ilchester (Lindinis) to Dorchester (Durnovaria). These roads mark the advance of Roman control, and later, Saxon migration, but may have formed a hard boundary beyond which Romanisation was resisted. Sites like Ham Hill, Maiden Castle, and Cadbury Castle retained their importance through the post-Roman period.

Roman finds near Pawlett, including a coin of Constantine I (dated to 337 AD), and the crossing at Combwich Passage, support the argument that trade and settlement persisted into the late Roman and sub-Roman periods. These locations line up with ancient crossing routes to the Polden Hills, another area with strong archaeological continuity.

Salt and Tin: Economic Lifelines

Roman and post-Roman activity in the region was not only defensive but economic. The Polden Hills, as reported in a 1942 article by St. George Gray, were a major site of salt extraction and Bronze Age hoards. This was not a backwater, it was an industrial zone, strategically positioned between sea and upland. Similarly, Cornwall?s tin, vital to Roman and early medieval economies, gave Dumnonia international significance.

A Patrol Along the Frontier: A Semi-Fictional Glimpse

From a high vantage point on Verne Hill on the Isle of Portland, a group of mounted Britons prepare for patrol. The site is ancient, possibly a Roman Saxon Shore fort, perhaps a hillfort, maybe a lookout post, but its commanding views across the Channel and coast are undeniable. As the sun rises over Jordan Hill, illuminating a ruined pagan temple, Owain, the patrol's leader, reflects. "The pagan sun rises in the East," he murmurs, "but it is setting on the faithful in the West."

The riders, armoured in mismatched chainmail and carrying spears, depart under the rising light. A sail glints offshore, a cargo vessel, likely bound for Armorica, the land now known as Brittany. A sanctuary for Britons seeking safety.

Owain leads them across the causeway toward the mainland. They skirt Radipole Lake, once tidal, deep, and Roman-used as a shipping port, and cross the River Wey. Climbing the ancient Dorchester Road, they ascend Ridgeway Hill and pass silent round barrows, relics of their ancestors. At Maiden Castle, smoke rises from roundhouses behind ramparts; life continues amid ruins.

In Durnovaria, the Roman city of Dorchester, aqueducts still run and paved roads remain intact. They pause to resupply, water their horses, and ride out via the northern gate. At a crossroads they find the road barricaded, baskets of stone and earth hastily dumped to block a Saxon route. Signs of recent movement put the riders on edge.

Through Yeovil, a Roman station with farmers and artisans, they press on to Ilchester (Lindinis). Owain exchanges news with a trader who claims to have once owned a hoard now buried again due to Saxon raids, possibly the famed Polden Hill Hoard. The trader, wizened and bitter, warns them that many are leaving the land.

Heading northwest, the patrol climbs onto the Polden Hills, a strategic Roman road above the wetlands. Inland lakes glimmer to either side. A local farmer offers water and recounts how just two summers prior he fled a Saxon raid, hiding on Dundon Hill. The patrol presses on through insect-thick marshland. The once-proud road becomes a rough track.

Near Combwich, they cross the Parrett River at low tide, splashing over the stony ford. The ancient Combwich Passage, used since Roman times, links to the ridge road on the Polden Peninsula , the artery between salt fields, villas, and trade ports.

As they reach the hill of Cannington, known in later chronicles as Cynwit, they see the old ramparts rising. Dismounting, Owain and his men are greeted by the garrison commander, eager for news from Portland. The frontier may be holding, but the strain is growing.

The Last Redoubt: Dumnonia's Survival

By the time of the Battle of Cynwit (878 AD), the borderlands shown in the map had become the contested frontier of Wessex and what remained of British rule. King Alfred?s refuges at Athelney and Langport show how this landscape continued to shape events long after the Roman departure.

Conclusion: A Boundary Reconsidered

The boundary of Dumnonia was never fixed, it ebbed and flowed with military, economic, and environmental pressures. But the map presented here offers a compelling reconstruction: a defensible, strategic line backed by rivers and marshes, extending from the Dorset coast to the Somerset Levels. The archaeology, from salt pans and hoards to hillforts and hidden crossings, supports the theory of a frontier that held for centuries.

This was not a line on a map. It was Britain?s last stand.

Related Articles

8 November 2025

How the Conquering Sun Became the Conquering Galilean26 October 2025

Elmet A Brittonic Kingdom and Enclave Between Rivers and Ridges24 October 2025

The Ebionites: When the Poor Carried the Gospel12 October 2025

Queen of Heaven: From the Catacombs to the Reformation4 October 2025

The Ancient Blood: A History of the Vampire27 September 2025

Epona: The Horse Goddess in Britain and Beyond26 September 2025

Witchcraft is Priestcraft: Jane Wenham and the End of England’s Witches20 September 2025

The Origins of Easter: From Ishtar and Passover to Eggs and the Bunny12 September 2025

Saint Cuthbert: Life, Death & Legacy of Lindisfarne’s Saint7 September 2025

The Search for the Ark of the Covenant: From Egypt to Ethiopia5 September 2025

The Search for Camelot: Legend, Theories, and Evidence1 September 2025

The Hell Hound Legends of Britain25 August 2025

The Lore of the Unicorn - A Definitive Guide23 August 2025

Saint Edmund: King, Martyr, and the Making of a Cult14 August 2025

The Great Serpent of Sea and Lake11 August 2025

The Dog Days of Summer - meanings and origins24 June 2025

The Evolution of Guardian Angels19 June 2025

Dumnonia The Sea Kingdom of the West17 June 2025

The Roman Calendar, Timekeeping in Ancient Rome14 June 2025

Are There Only Male Angels?