Written by David Caldwell ·

What Came First The Yew or the Church? A Journey Through Groves, Graves, and Time

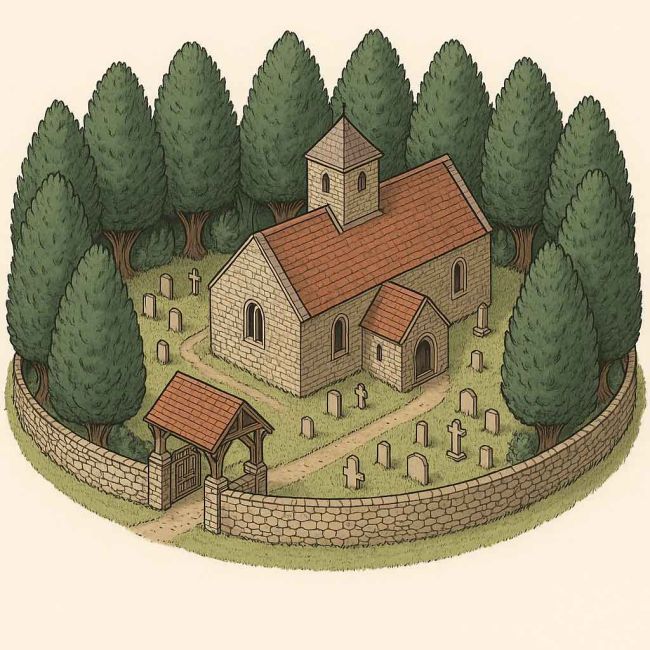

From ancient tombs to modern rooftops, the yew tree has remained an enduring companion to human ritual and reverence. In the British Isles, few sights are as quintessentially evocative as a gnarled yew brooding over the stones of an old country churchyard. But which came first, the yew or the church? And could these enduring trees be the last living witnesses of a time when Britain was a land of sacred groves?

Yews and the Ancients: Egypt, Greece, and Rome

The tradition of planting sacred trees around burial sites is not uniquely British. The ancient Egyptians, Greeks, and Romans all associated evergreen trees such as the yew, elm, and cypress with death, mourning, and immortality. These trees were planted around tombs not only as markers but as spiritual guardians. The Greeks, it is said, imported the custom from Egypt; the Romans from the Greeks; and the Britons, in turn, from the Romans. The yew thus acquired a sacred aura through continuous association with burial rites and ceremonial space.

This sacred symbolism may help explain the curious legend that Pontius Pilate was born in Scotland, under the boughs of the ancient Fortingall Yew, reputed to be over 3,000 years old. Though the tale is likely apocryphal, it reflects a powerful truth: that these trees are entwined with the very oldest strata of European cultural memory.

The Pope's Advice: Christianity Meets the Sacred Grove

When Pope Gregory I sent Augustine to Christianise Britain in the 6th century, he instructed him not to destroy pagan temples and groves but to repurpose them. Let the people continue to gather at their sacred places, he wrote, but give those places new Christian meanings. The result? Many of Britain?s oldest churches are built directly on sites that were already holy. In some cases, the only trace of the older religion may be the towering yew, its roots sunk deeper than any foundation.

In Kent, yew trees were once commonly referred to as "palm trees", a reference to their use in Palm Sunday celebrations as a substitute for palm fronds. This linguistic remnant hints at the continuity of ritual through botanical stand-ins, blending Christian liturgy with local flora.

A particularly evocative example of sacred continuity lies at the Druids' Grove near Box Hill in Surrey. Nestled in a steep-sided yew-filled gorge above the River Mole, this shadowy, ancient woodland is a rare surviving remnant of what may once have been a pre-Christian sanctuary. The name itself is a Victorian romanticisation, but the grove?s haunting presence, and the immense age of some of its trees, suggests a space long held in reverence.

Folklore and Fear: The Dual Nature of Yew

In folklore, yew branches were believed to ward off witches, goblins, and evil spirits. Carried in funeral processions, they were seen as symbols of resurrection. But the yew also inspired dread: its leaves, bark, and seeds are toxic, especially to livestock. The danger of overhanging branches poisoned many an unfortunate horse or cow, as 19th- and early 20th-century newspaper reports confirm.

Yet this very toxicity may have served a purpose: protecting the sanctity of burial grounds from grazing animals or scavengers like wolves. Thus, the yew took on a role both protective and deadly, a botanical guardian of the dead.

A Natural History of Death and Rebirth

The distinction between Irish and British Druidry adds a compelling dimension to our understanding of the yew's sacred role. In Ireland, the yew was the preeminent tree of Druidic reverence, more so than the oak. In Britain, while the oak held an important symbolic role, there is strong evidence that the yew was equally revered, if not central to certain rites. This raises an intriguing question: could the legendary sacred groves on the island of Mona (Anglesey), described by Roman historians as the heartland of Druidic worship, have been groves of yew rather than oak? If so, and given the longevity of the species, could any of those ancient trees still be alive today, quietly witnessing the passage of millennia?

The yew?s biological resilience mirrors its symbolic one. It can live for thousands of years, regenerate from hollow trunks, and appear dead while new shoots sprout from within. One 1887 writer described yews as "colonies of individuals" rather than single trees, a living metaphor for immortality. In Ireland, the yew was the Druids? secret tree, more revered than the oak. The rowan, hawthorn, and blackthorn were its mystical companions.

From Archery to Allegory: Other Theories

Some theories claim that yews were planted in churchyards to provide wood for longbows, especially during the medieval wars when yew bow-staves were in high demand. However, this utilitarian explanation has been dismissed by many antiquarians as insufficient. The spiritual and cultural role of the yew seems too deeply rooted to be reduced to warfare alone.

The Ankerwyke Yew and Fountains Abbey

Among Britain's most storied yews is the Ankerwyke Yew, now protected by the National Trust, having narrowly escaped being felled for a golf course. Located opposite Runnymede by the Thames, site of the signing of Magna Carta, this tree is thought to be over 2,000 years old, based on measurements and early scientific methods of ring estimation. A 19th-century study compared its dimensions and growth rate to yews in Wales and Derbyshire and calculated ages based on an average of 44 rings per inch, suggesting a remarkable antiquity. This blend of empirical observation and reverence highlights the long-standing human effort to date and preserve these living monuments.

Estimating the Age of a Yew Tree

Determining the exact age of a yew tree is notoriously difficult, especially for older specimens whose centres have rotted away. However, a common method involves measuring the girth (the circumference of the trunk) and applying a conservative growth rate.

A simple formula is:

Estimated Age (years) = Girth in inches ? Average Annual Growth in inches

For slow-growing ancient yews, a growth rate of 0.5 inches per year is often used. So:

- If a yew has a girth of 260 inches (about 6.6 metres),

- Estimated age = 260 ? 0.1 to 0.5 = between 520 and 2,600 years.

Most scholars opt for the slower rate when dealing with ancient yews in churchyards, as these trees often grow in poor soils and shaded conditions?slowing growth even further. Using the slowest accepted rate gives us some of the oldest living trees in Europe.

At Fountains Abbey in Yorkshire, the story is told of monks who, in the harsh winter of 1132, found shelter under a stand of yews known as the Seven Sisters. These trees may have predated the Abbey itself, offering sacred cover to Cistercian monks before their oratory was even built. The presence of ancient yews at such sites underscores their role as primordial sanctuaries.

An 1833 account notes that some yews in churchyards were already of great age at the time of the church's foundation, suggesting that in many villages, the tree may have come first.

Legends and Records: Painswick, Selborne, and Statutes of the Past

In Painswick, Gloucestershire, an enduring legend held that the churchyard could support only 99 yew trees, the hundredth would always die. Local lore attributed this to divine will or ancient taboo. But in 1930, William Ireland, who had spent two decades trimming the trees, declared there were in fact more than 100. A later revelation in 1963 revealed that a prankster had secretly poisoned the hundredth tree to uphold the legend. Interestingly, as early as 1930, William Ireland himself speculated that one of the yews had been deliberately poisoned, possibly to improve the view from a nearby house, suggesting the legend may have been actively maintained by more than mere coincidence. Despite the myth?s collapse, Painswick still boasts one of the largest yew collections in England, with over 100 trees forming an avenue of ghostly green.

One 19th-century clipping also claimed that Edward I issued a statute banning yews from pastureland due to their toxicity to cattle, leading to their cultivation in churchyards. Though no such statute has been found in surviving law codes, the belief speaks to the intersection of practicality and myth in the yew?s long story.

The archaeological evidence from the Great Yew at Selborne, Hampshire, which fell in a storm in January 1990, offers a fascinating case. Excavation showed that the churchyard had been in continuous Christian use, based on east?west graves, since at least Domesday (1086), with architectural evidence confirming a church by the 12th century. The deepest burial, dated to c.1200?1400 AD by pottery, cut into undisturbed subsoil presumed to have been occupied by the yew at that time. With a trunk diameter suggesting an age of 200?300 years in the 13th century, the yew could have been seeded around AD 900, possibly by even older nearby yews. This raises the tantalising possibility that the Great Yew was already rooted in sacred soil before the first Christian grave was dug.

20th-Century Echoes: The 2002 Topping Ceremony

Astonishingly, the ancient custom persists. In 2002, at a construction site in Lichfield, builders from Walton Homes observed a "topping out" ceremony by placing a branch of yew on the last brick to ward off evil spirits. This rare survival of an ancient tradition shows that the yew?s symbolic potency endures even in modern commercial architecture.

Britain?s Living Monuments

The yew tree is more than a feature of the churchyard. It is a living monument, older than the walls it shades, older perhaps than Christianity in these isles. Whether planted to mark the sacred, to ward off harm, or to honour the dead, its roots run deep into the soil of British cultural memory. In many cases, it seems the answer to our question is clear:

The yew came first.

Related Articles

8 November 2025

How the Conquering Sun Became the Conquering Galilean26 October 2025

Elmet A Brittonic Kingdom and Enclave Between Rivers and Ridges24 October 2025

The Ebionites: When the Poor Carried the Gospel12 October 2025

Queen of Heaven: From the Catacombs to the Reformation4 October 2025

The Ancient Blood: A History of the Vampire27 September 2025

Epona: The Horse Goddess in Britain and Beyond26 September 2025

Witchcraft is Priestcraft: Jane Wenham and the End of England’s Witches20 September 2025

The Origins of Easter: From Ishtar and Passover to Eggs and the Bunny12 September 2025

Saint Cuthbert: Life, Death & Legacy of Lindisfarne’s Saint7 September 2025

The Search for the Ark of the Covenant: From Egypt to Ethiopia5 September 2025

The Search for Camelot: Legend, Theories, and Evidence1 September 2025

The Hell Hound Legends of Britain25 August 2025

The Lore of the Unicorn - A Definitive Guide23 August 2025

Saint Edmund: King, Martyr, and the Making of a Cult14 August 2025

The Great Serpent of Sea and Lake11 August 2025

The Dog Days of Summer - meanings and origins24 June 2025

The Evolution of Guardian Angels19 June 2025

Dumnonia The Sea Kingdom of the West17 June 2025

The Roman Calendar, Timekeeping in Ancient Rome14 June 2025

Are There Only Male Angels?